The Right to Roam campaign https://www.righttoroam.org.uk/ has taken a far broader approach to access rights than has traditionally been the case in England and has been building a broad campaign for a new legal right of access on the Scottish model.

One of the outdoor recreational activities that has been highlighted by that campaign is wild swimming and in April, to mark the anniversary of the famous mass trespass that took place on Kinder Scout in 1932, there was a mass swim at the Kinder Reservoir. Although described as a “mass trespass” by the Guardian (see here), it was not actually a “trespass”. Most reservoirs in England are now owned and managed by private water companies but were was once public land. The legislation that led to the sale of public water assets in England included a legal duty for the new companies to continue to provide public access on land and water. Despite that many companies have put up “no swimming notices”.

The Open Swimming Society has produced an excellent summary of the law in England along with more detailed briefings (see here). The law is quite complex but the OSS explains how people can lawfully swim in far more places than is commonly thought. The fundamental problem, as it was prior to the Land Reform (Scotland) Act, is that people get worried that they might be treated as a trespasser and this puts them off going to many places to swim. If you have not read it, Roger Deakin’s Waterlog provides a wonderful and humorous description of the pleasure and the fear involved in swimming down a river in Hampshire (watch out for the water bailiffs). Not many people want to put themselves through the risk of being confronted which is exactly why the Open Swimming Society and Right to Roam campaign are calling for access rights in England and Wales.

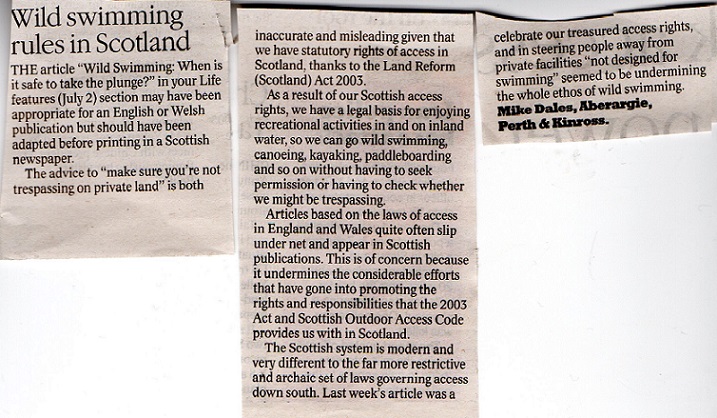

A secondary part of problem, which still exists in Scotland, is that just like at the Kinder Reservoir people are still being told they don’t have access rights when they do. The letter published in the Herald last Sunday by Mike Dales (who has written on access rights for this blog) was therefore very welcome:

Scotland doesn’t lack “no swimming” signs either, often erected for safety reasons when the Land Reform (Scotland) Act and Scottish Outdoor Access Code created a framework in which people exercising those rights need to take reasonable responsibility for their own safety.

I am often critical of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority but this sign from Luss Pier provides a very good illustration of how our Public Authorities should manage those issues:

All credit to the LLTNPA. Warn people of the dangers and risks, where it is reasonable to do so, but don’t try and stop people from making their own decisions by “No” signs which undermine access rights.

All credit to the LLTNPA. Warn people of the dangers and risks, where it is reasonable to do so, but don’t try and stop people from making their own decisions by “No” signs which undermine access rights.

We could do with more people in Scotland who, like Mike, are prepared to challenge misleading information about our access rights wherever it appears, whether this is in the media or on the ground. It would be interesting to know how many “no swimming” notices have ever been reported to access authorities? I certainly can’t think of any protests. Maybe just as England has something to learn from Scotland in respect of creating a right to roam, Scotland has something to learn from England about how to draw attention to cases where rights are ignored.

Toxic algal blooms are a hazard.