Last week I took two relatives from Australia, ecologists both, on a tour of Scotland which included parts of both of Scotland’s National Parks. Our first stop was Inveruglas, on the west shore of Loch Lomond, land owned and managed by the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority.

Last week I took two relatives from Australia, ecologists both, on a tour of Scotland which included parts of both of Scotland’s National Parks. Our first stop was Inveruglas, on the west shore of Loch Lomond, land owned and managed by the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority.

It was good to find the cafe and toilets open and plenty of bins, although the one by the steps leading to the viewing tower had litter strewn around it:

I was too engaged with my guests to think to open the bin to see if it was full, the most likely explanation for what you can see.

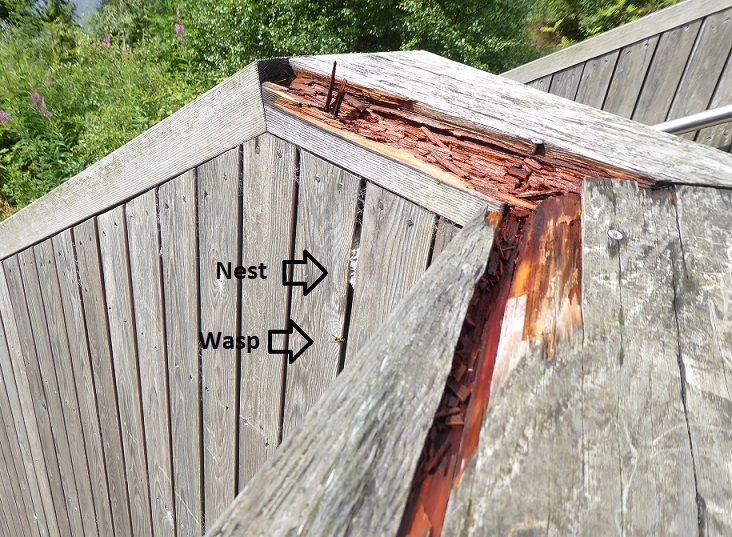

The viewing tower, which was named An Ceann Mor, was opened by Scottish Ministers in 2015 and is promoted by the LLTNPA as part of Scotland’s Scenic Routes initiative (see here). Unfortunately after the initial capital expenditure it does not appear to have been maintained.

The rotten wood provides great habitat for wildlife and an opportunity to watch insects close up but raises questions about how long the tower will remain safe to use.

Just eight years after construction the top part of the tower has been cordoned off, presumably for safety reasons, while some of wooden steps – nicely designed in my view – are also rotting away.

This is not an isolated maintenance failure on the part of the LLTNPA. Earlier this year they installed a new metal bridge over the Bracklinn Falls (see here) after the award winning wooden one, installed in 2011 for £110k (see here), had failed due to lack of maintenance. The fear now is that the LLTNPA will decide to replace the wooden steps and tower at Inveruglas with recycled plastic in order to reduce future maintenance costs. This is what they have done with benches on some of their sites and is totally out of keeping with the natural environment.

This is not an isolated maintenance failure on the part of the LLTNPA. Earlier this year they installed a new metal bridge over the Bracklinn Falls (see here) after the award winning wooden one, installed in 2011 for £110k (see here), had failed due to lack of maintenance. The fear now is that the LLTNPA will decide to replace the wooden steps and tower at Inveruglas with recycled plastic in order to reduce future maintenance costs. This is what they have done with benches on some of their sites and is totally out of keeping with the natural environment.

The basic problem is that none of the LLTNPA’s plans to invest in visitor infrastructure, whether constructed out of natural materials or not (paths, piers, toilets etc) appears to include any provision for maintenance.

Maintenance of visitor infrastructure of course requires ongoing expenditure and the record of the LLTNPA suggests that the senior management at the LLTNPA try where they can to avoid this. That is a recipe for wasting yet more of the capital investments funded by the Scottish Government.

Meantime at Inveruglas and other sites they own the LLTNPA continues to plant trees in unnecessary polluting plastic tree shelters.

Such planting appears to stem from the mistaken belief, shared by many including Scottish Ministers, that woodland cannot restore itself and that tree planting is the way to address the climate and nature crises. The evidence from Inveruglas illustrates the folly. Why plant this oak tree when there is perfectly good birch which has seeded naturally a few feet away and just round the corner oak is regenerating naturally?

The answer appears to be that the LLTNPA wants to be seen to be doing something to help nature on its own property, instead of showcasing what is happening naturally.

Large sections of the west shore of Loch Lomond is covered with oak woodland, some of which is protected. If grazing pressure was removed and the areas outside forest plantations left to regenerate naturally, oak would become the dominant form of woodland along the shore, accompanied by smaller pockets of alder and ash and alder.

Within this ecological context, why then has the LLTNPA planted a Scots pine among all the luxuriant and thriving vegetation?

This Scots pine is out of place and out of habitat. It might have taken years and a large fire for pine to colonise this site naturally. This is what happens, however, when the tree planters and landscape gardeners are allowed to take over without any consideration of the wider ecological context or to take responsibility for the consequences of what they do.

The LLTNPA is unfortunately getting it wrong ecologically at Inveruglas and in the course of that wasting scarce resources.

What needs to happen

The tree planting at Inveruglas is a great shame because what is happening naturally is a success story. An Ceann Mor, which stood starkly out against the horizon eight years ago, is now surrounded by lush vegetation and self-seeded trees and from most directions obscured from view. The same has been happening across most of the remainder of the site.

The LLTNPA owns very little land on which to demonstrate good practice but they could use Inveruglas. It provides an opportunity to demonstrate to local landowners how their policy, that the preferred means of woodland expansion in the National Park should be by natural regeneration, would work in practice. They could also use Inveruglas to show that it is possible to do this while welcoming significant numbers of visitors (instead their draft National Park Partnership Plan suggests that visitors may be need to prevented going to some places to enable conservation). Inveruglas therefore could, with a little will, be used demonstrates a win win for the National Park’s statutory objectives and that conservation and the enjoyment of the countryside by visitors could be promoted together.

For this to happen all the LLTNPA Board needs to do is use their National Park Partnership Plan, which is currently out for consultation, to commit to stopping any more money being wasted on trying to plant trees and use it in instead to maintain the wooden infrastucture that complements the woodland and enhances the visitor infrastructure. At the same time they need to scrap the suggestions in the draft NPPP that somehow visitor enjoyment of the countryside and conservation are incompatible objectives and that the focus of the National Park Authority needs to shift from visitors to nature (see here).

1 Comment on “Wood and woodland at Inveruglas – the LLTNPA is missing a great opportunity”