The damage caused by Scotland’s exceedingly high numbers of red deer and muirburn are the two main issues that need to be tackled if we are to tackle the nature and climate emergencies in the uplands. This post takes a look at the three changes in the law the Scottish Government announced yesterday (see here) which are intended to “make it easier to reduce unsustainable deer numbers”.

Background – crisis what crisis?

Following numerous previous inquiries, the Scottish Government set up the Deer Working Group in 2017 to consider issues around the management of deer in Scotland. It produced its final report, in some ways the most comprehensive yet, in February 2020 (see here).

Dave Morris produced an analysis of the report on parkswatch within a week (see here) and identified areas where urgent action was possible, including the use of compulsory Section 8 measures to control the deer at Caenlochan (pictured above). The Scottish Government by contrast took over a year to respond before in March 2021 (see here) they accepted most of the Deer Working Group’s ninety-nine recommendations.

Another fifteen months on in July 2022, the new minister for biodiversity, Lorna Slater expressed her determination to implement the recommendations of the Deer Working Group “as a priority” in an opinion piece in the Herald in July 2022 (see here). It has taken eleven months since then for the Scottish Government to produce two amendment orders to the law, comprising a few hundred words in total. As Dave Morris argued, such tweaks to the law could have been implemented immediately. Instead the changes to the stag stalking season in the Deer (Close Seasons) (Scotland) Amendment Order 2023 will come into effect on 21st October this year, three and a half years after they were recommended by the Deer Working Group. (It is not yet clear when the other amendment order, about use of firearms to control deer, will come into effect).

The Scottish Government’s announcement and the changes to the law

The Scottish Government’s news release, was a tad misleading. The “disinformation” was reprinted more or less word for word by various parts of the mainstream media.

The release started by claiming “Land managers will be given more powers to help control Scotland’s rapidly growing deer population after updated rules were introduced to Parliament this week”. The truth is that the existing legislation, designed to protect sporting interests, has restricted the power of most land managers to shoot deer and thus control their numbers. The amendment orders don’t give land managers any new powers, they simply lift a few of the current restrictions that make it very difficult for farmers, foresters and others to shoot deer.

“The refreshed regulations will allow authorised land managers to:

- cull male deer across a longer period of the year

- use specialist scopes known as ‘night sights’ to cull deer at night

- use ammunition which is less damaging to venison products

I had to read the regulations to understand the changes. They show that the closed season for shooting the males of all five species of deer found in Scotland is to be abolished completely, as recommended by the Deer Working Group, and not just for “a longer period of the year”. So why was the Scottish Government so reluctant to state this?

And in respect to “less damaging” ammunition, the effect of the regulations is to reduce the minimum weight from 6.48 grams to 5.3 grams. This will make it possible to use non-lead bullets in the smaller rifles used for sporting purposes. NatureScot and Forestry and Land Scotland have, to their credit, developed a supply chain to provide non-lead (copper) bullets for the heavier rifles they use to cull deer (it is safe to eat their venison). But the minimum weight restriction on ammunition has prevented a non-lead alternative being developed for smaller guns.

These changes reflect the Scottish Government’s response to the Deer Working Group report but NOT what it recommended:

The Report was very clear that the current open season for shooting hinds – 21st October to 15th February for red deer hinds – was too short to allow numbers to be effectively controlled. The Scottish Government effectively rejected this on the grounds that giving hinds a longer break from being shot (outside late pregnancy and when they had young) had “significant welfare value”. Why hinds, but not stags, merited this treatment was not explained.

Nor was any mention made of the welfare of all the other animals, some of whose very survival is at stake, because of the way deer have destroyed their habitat.

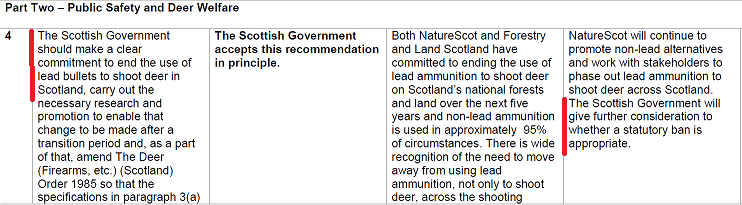

The change in the law on ammunition also goes less far than the Deer Working Group which recommended lead should be banned after a transition period:

While the Scottish Government stated it accepted this recommendation in principle, all the change in the law will do is make it possible for a market to develop in lead free ammunition for smaller guns. Whether it does so will depend on whether sporting estates want to change or not. In itself the change to the law will do little to “make more venison available to both foreign and domestic markets”. The venison eating public deserve to know whether what they are eating is completely lead free or not but years after lead was banned for other purposes it is allowed to continue in the sporting world. Nor will the change prevent lead being spread across the wider environment, wwhich was a major concern of the Deer Working Group. Lead like plastic needs to be kept out of the countryside.

What difference will these changes to the law make to red deer numbers?

The limited open season for shooting red deer stags in Scotland (1st July to 21st October) – in England the season runs from 1st August to 30th April! – has formed a major obstacle to those wanting to reduce deer numbers in Scotland, partly because the period was so restricted but also because it was the time stags are hardest to shoot, having taken to the hills. Being able to shoot stags when they are more likely to be on the lower ground and without having to apply for a special license will be of real help to some managers.

Unfortunately, without also changing the season to shoot hinds, the direct benefits are likely to be limited. As long as red deer hind numbers remain high, as is the case on most stalking estates which treat them as having little “sporting value”, the population of stags will simply be replenished each year. There is limited logic in making it possible to shoot stags year round if hinds can still only be shot in the most challenging part of the winter.

The silver lining here, however, is the legalisation of “night sights” should make it easier to cull significantly more hinds over the winter when daylight hours are at their shortest and when the deer tend to descend to the lower and more accessible ground at the end of the day. This should really help conservation minded owners, foresters etc.

Indirectly, however, the abolition of the stag closed season could have a significant impact on the ethos of stalking estates and the way they are managed, not least because their capital value has been determined in part by the number of stags on the property. While some landowners may continue to want to stalk red deer only when they are in their prime and hardest to shoot, that ethos has been slowly eroding, as the proliferation of ATVs and bulldozed tracks shows. Some of the more commercially oriented estates or conservation owners such as the NTS at Mar Lodge, could start offering stag stalking all year round. That could be good for jobs and offers the possibility that some of the estate lodges which are currently only opened up for a few weeks a year are used for extended periods.

The extension to the stag stalking season also potentially risks causing some problems for outdoor recreation and the exercise of access rights. Traditionally, hill goers have exercised some restraint during the stag stalking season and accepted, for example, advice to keep to paths and ridges: but what now happens if some estates try to apply those “restrictions” year round?

There is also the complex question of how traditional stalking estates will react now that it is much easier for other landowners to start shooting more stags?

At present the limited open seasons causes specific challenges for conservation owners, like Wildland Ltd or the National Trust for Scotland, and farmers and foresters who are trying to reduce deer numbers. Where such owners have upped shooting activity in the stalking season, some deer move onto neighbouring land only to return when it is safer to do so. If for this or any other reason the owner then applies for a license to shoot red deer out of season to prevent damage, it then has to face the likelihood it will be publicly attacked by the Scottish Gamekeepers Association. This happened to the John Muir Trust in Assynt in January (see here) and more recently to NTS in Glen Coe (see here).

The Scottish Gamekeepers Association has responded to the changes with a statement (see here) from Alex Hogg, MBE, who claimed that “doing away with male deer seasons downgrades animal welfare in Scotland and may actually lead to numbers and forest damage increasing”. This from an organisation that treats large numbers of animals as “vermin”. Now the tables have partly turned, it will be interesting to see how the actual owners of stalking estates respond when “their deer” are culled on neighbouring land. Could some, for example, start to use fencing to keep deer in rather than out?

The wider implications of the changes to the law

Had the Scottish Government amended the law on closed season for hinds, as the Deer Working Group recommended, at the same time as abolishing the closed season for stags and legalising the use of night sights, that could have had a major impact on the deer population in Scotland and had a number of beneficial consequences.

These changes to the law, however, while welcome and not before time, are likely to have a limited impact on land managers ability to reduce and control the number of red deer in Scotland. They will not address the “devastating impact on our land due to trampling and overgrazing” which Lorna Slater stated she wanted to see in the news release. Nor do they address the issue that “An occupier should be able to protect their interests in an unenclosed woodland on land they occupy, not just in a woodland on land that is considered to be enclosed by a stock proof fence” as referred to in the Deer Working Group report.

This is a lost opportunity and not just in terms of addressing the direct environmental damage caused by deer in Scotland, with all the implications that has for tackling the nature and climate emergencies. If foresters were able to control deer effectively, for example, there would be no need for Scotland to spend a small fortune each year on expensive and ineffective deer fencing: natural regeneration could then replace planting as the main method by which woodland expanded, saving yet more public money. If the owners of large estates could shoot deer for most of the year, the justification for many of the hill roads which now mar much of Scotland’s landscape would disappear.

The challenge for Lorna Slater now is not just to stop referring to red deer as Scotland’s “most iconic species”, which plays into the hand of stalking estates, but to find a way to implement the commitment made by the Scottish Government in 2021 and review the closed season for hinds sooner rather than later.

Being the Minister who is also responsible for NatureScot and National Parks provides a number of opportunities to do so. Ms Slater could, for example, ask NatureScot to consider issuing licenses to cull hinds across both National Parks, as per the periods recommended by the Deer Working Group. The grounds for this would be that the high numbers of hinds are causing significant environmental damage, contrary to the statutory purpose of our National Parks. If the impact of such a measure was properly monitored, it could then be used to justify a further review of the Deer (Closed Seasons) Order. After sixty years of procrastination on the deer issue, it is time for much more urgent action.

And the place for urgent action to start, irrespective of any future legislative changes, is around Braemar where the Balmoral and Invercauld estates have failed, for decades, to take effective action to reduce grazing pressures down to levels which permit the natural regeneration of all natural vegetation. Surely we should not have to wait any longer for our Monarch to deal effectively with the Monarch of the glens. Queen Victoria is no longer on the throne. Time for land use on these two estates to be brought into the 21st Century.

“Climate emergency”: https://youtu.be/3q-M_uYkpT0

It may interest the reader to learn that despite deer numbers being generally kept in balance with the available sustainable resources over large parts of the uplands, it is within the ill-designed and underman-managed forest environment that the numbers of deer have increased in the past years, not across open moorlandnwjere they can be monitored and managed, generally by competent and knowledgeable stalkers.

To think for one moment that culling more males of a species with polyamorous instincts will do anything to reduce overall numbers in any environment, be that forest or open hill, is simply showing how little understanding of the animal and its behaviour one has. Routine checks are made by SNH on the cull levels of all Deer Management Groups across upland Scotland, and any estate found wanting is soon ‘encouraged’ to raise its game accordingly; not so within the state sector, where the deer (after all, a woodland animal) are simply shot at on sight, day and night, on the whole irrespective of sex nor season – 80% of all deer culled within the National Forest Estate during the winter ‘free-for-all’. And yet the numbers appear to be growing – after twenty years of this approach – might it suggest that this approach may be in line for a review, or is it felt that it is working? When the contractors are rewarded for the ‘if it’s brown, it’s down’ approach, inevitably the easy, lazy and nearest deer (usually stags) are the ones mostly accounted for, but it is the female which carries the next generation.

The piece seems to suggest that shooting more deer is easy to achieve. Ask a forester! Such cheap talk is, much like the glib presumption of ‘climate emergency’, ill-informed, and downright mistaken.

If you rely on the ludicrous misinformation on atmospheric CO2 and its greenhouse properties provided by Prof. Salby (to which you link) then it is little wonder that you are so misinformed. Salby, quite frankly, is a joke with no credibility amongst climate scientists or, indeed, anyone with a competent understanding of climate science.

Likewise you don’t appear to have understood Nick’s piece, which emphasised the importance of shooting hinds and recognised the difficulties of doing so with the present open season being “too short to allow numbers to be effectively controlled” particularly as it was “in the most challenging part of the winter.”

Anyone might assume from a few rather short-sighted remarks made by critics of rigourous deer culls, that the density of red deer within any one area is static. It does not take much awareness or a very long stay anywhere in the highlands today, to see this is not true. When the noise and chaos of forestry felling and trans- shipment operations disrupt a habitat , quiet for decades, then the herds move away. The disruption when fresh ( inexcuseable) tracks are dug, blasted, and bulldozed across previously unblemished virgin hillsides, leads to the same mass migration. The grazing pressure transfers to denude nearby marginal agricultural land. This year any possibility of haylage or indeed Hay in our local fields is already problematic. Nearby a 500 Ha forestry block is in the early stages of being felled. Over the past 9 months New roads to cope with huge machines have been rock pecked and ‘borrow’ pits dug. A new link span bridge now permits ships to dock to collect the timber. That deer population has moved somewhere quite close but much quieter. We can count up to 15 beasts in our croft field most mornings. But should anybody go to scare them or start shooting at them, they would surely disappear only until the field became less dangerous for them to graze in once again.