Galloway is one of the areas most likely to be selected as Scotland’s third National Park (see here) due to high levels of support locally. That support has been driven by concerns about the increasing encroachment of windfarms, the intensification of agriculture in the coastal areas and the impact of commercial forestry plantations, all of which have had serious adverse consequences for both the landscape and local communities. To that list we now need to add the unsustainable use of plastic tree tubes as a means of increasing the extent of native woodland.

In the twenty months since I last visited Forrest Lodge below the Rhinns of Kells, both sides of the minor road that leads to it from the A713, have been planted with trees enclosed in plastic shelters. The plastic has created a horrible eyesore, offsets any benefit that the trees might have as temporary carbon sinks because it is made from fossil fuels and is damaging for both humans and the natural environment.

There is a strong argument that we need to start planting native deciduous trees for commercial purposes, not least so that we can return to making products out of wood rather than plastic. But, as is shown by continuous cover forestry elsewhere in Europe, there is no need to plant trees in uniform rows to produce useful timber and enclosing those trees in plastic defeats the purpose.

Under the continuous cover forestry system on the continent, trees are rarely planted but allowed to regenerate naturally, with foresters then managing the woodland to produce useful timber. As long as deer numbers were properly controlled, much former agricultural land would quickly revert to woodland in Scotland, as it has in Europe, but without the damage to soils caused by planting trees and encasing them in plastic. Natural regeneration could provide the basis for continuous cover forestry.

In terms of carbon emissions and the natural environment, however, there is also an argument that it might have been better to continue to use these fields for agricultural purposes. Grasslands have been shown to lock up carbon in soils while wool from sheep is a far more sustainable and less polluting product than clothes derived from plastic. Meadows are good for biodiversity.

Whatever the difficulties in choosing between woodland and agriculture, we should be doing everything we can to stop the use of plastic in the countryside. Instead, at present, the public is paying for it through Scotland’s forestry grant system which is unfit for purpose.

The Forrest Lodge estate, which appears to be responsible for all these plastic tree tubes, is also the global headquarters of Natural Power, a green energy consultancy “working to create a world powered by renewable energy” (see here).

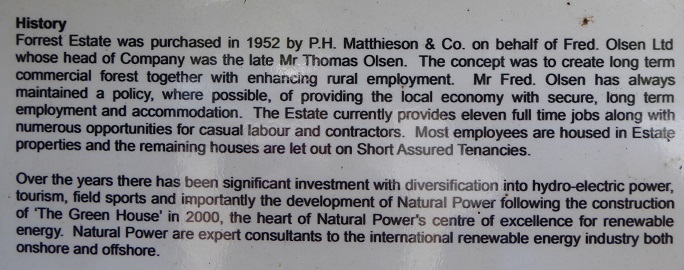

Natural Power was bought by Fred Olsen in 1999 and the companies through which it now provides services are owned by Fred Olsen Ltd, the same company that bought Forrest Lodge 70 years ago. The connections between the two are explained below:

Since my visit in August 2020 a number of electric vehicle charging points appear to have been installed at the Natural Power HQ:

Meanwhile, in the field on the opposite side of the road and in full view of the Natural Power HQ, hundreds of trees have been planted in plastic tubes (despite the obvious natural regeneration):

This illustrates some of the disconnects in current green thinking and policy in Scotland:

- We cannot phase out fossil carbon extraction by converting to renewable energy unless we also stop using fossil carbon to make plastic;

- Paying for plastic tree tubes to plant trees to offset carbon destroys much of the potential benefit of planting trees; and

- The forestry industry in Scotland is still focussed almost entirely on short-term timber production (growing as many trees as possible in the shortest amount of time) and takes almost no account of the impact this has on nature and the natural environment.

We need some joined up thinking. What the Natural Power and Forrest Lodge illustrates is that is not going to happen, even among well-intentioned people who are part of the same organisation, unless the joined up thinking starts at the top, we reform the public subsidy system and there are mechanisms to ensure it is put into practice on the ground. That, I believe, is where National Parks could come in.

Galloway has so far been mentioned more than any other area (see here) in the Scottish Government’s preliminary consultation on a new National Park, due to close on 6th June. Interestingly, the vast majority of those ideas and comments that have been submitted by the public to date (see here) are about what National Parks should and shouldn’t be doing rather than where they should be located. And topping the list of ideas is tackling the climate and biodiversity crises. A National Park Authority that had intervened to prevent the plastic tree planting at Forrest Lodge or had the power to ensure agricultural and forest subsidies were only payable if they benefitted the natural environment would, I believe, be popular.

Ending the subsidy and use of plastic tree tubes of course is relatively simple. Far more challenging for a Galloway National Park would be tackling the damaging impacts of current land-use:

Or indeed how to enable the public to travel and enjoy what remains of the delights of Galloway in a sustainable matter. There are just two buses a day between Dalmellington and St John’s Dalry and no links to Forrest Lodge. Until that changes the only practical way to enjoy the Rhinns of Kells will be by car – mea culpa!

Gallowfarce more likely and not a real national park—just like the existing ersatz ones we have now