Last month, in a great piece of investigative journalism (see here), Rob Edwards from the Ferret obtained a copy of a document called the “Salisbury Crags Rock Risk Management Options Appraisal 2021” from Historic Environment Scotland (HES). This revealed that HES are seriously considering trying to close the Radical Road in Edinburgh permanently. Although I, with others, have been campaigning against the closure of the Radical Road (see here) and (here), I had not figured out this document existed. Half the challenge in making FOI requests is knowing what to ask for, so all credit to Rob for doing so.

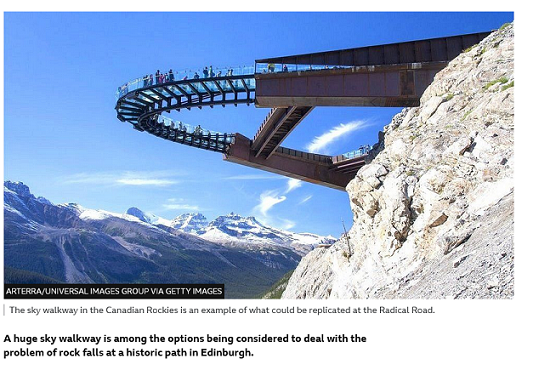

Subsequently the BBC (see here) has given additional coverage to the most ridiculous idea in the Options Appraisal Document (above). This seems to have been floated to give the impression that the closure of the Radical Road has nothing to do with money, only risk management. There is, of course, no money to pay for such a structure which would be totally inappropriate in the historical environment of Holyrood Park.

Subsequently the BBC (see here) has given additional coverage to the most ridiculous idea in the Options Appraisal Document (above). This seems to have been floated to give the impression that the closure of the Radical Road has nothing to do with money, only risk management. There is, of course, no money to pay for such a structure which would be totally inappropriate in the historical environment of Holyrood Park.

Then, a week ago, in a very welcome move (see here), the Cockburn Association (set up to protect Edinburgh’s historic heritage), Scotways, Mountaineering Scotland and Ramblers Scotland wrote a joint letter letter to the Chief Executive of HES, Alex Paterson, asking for an urgent meeting about the blocking off of the Radical Road. The letter points out something I had missed: that the Radical Road is a Right of Way and that in failing to follow the procedures required to close or divert a right of way they had acted unlawfully. That begs further questions as to why the City of Edinburgh Council, which has a statutory duty under the Countryside (Scotland) Act 1967 to protect rights of way, has not intervened to object to HES’ actions?

In my view, however, the Cockburn Association, Scotways, Ramblers and Mountaineers are unlikely to persuade HES to reverse their decision to ignore both the law on Rights of Way and access rights by calling for a Strategic Management Plan for Holyrood Park. In the Ferret article I was quoted as saying it is well past time that the Holyrood Park Regulations, which give HES unlimited powers to act contrary to access rights, were amended to bring them into line with the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. Until that anomaly is resolved by the Scottish Parliament, there is little chance of HES producing a plan for Holyrood Park that respects access rights

This post – which I had started to write a month ago – looks in more detail at what HES’ options appraisal tells us about their thinking and their understanding of the law as it affects public access.

HES’ options appraisal

The Options Appraisal is not a neutral document but has been written in such as way as to encourage the HES Board to believe they have little option but to approve the permanent closure of the Radical Road. There are several examples of serious bias and lack of balance on non-legal matters which one would hope Board Members, if given the opportunity, might challenge:

1) HES staff have applied different standards to their assessment of the impact of temporary and permanent barriers. Contrast “the current mitigation measure with temporary barriers and advisory signage is not satisfactory in the park setting” with their conclusion that the “physical/visual impact” of permanent new exclusion barriers – i.e. an enormous fence round the bottom of Salisbury Crags – will be “moderate”. At the same time they say nothing about the appropriateness of the Skywalk option in the Park Setting, only that the visual impact would be “very high” and “unlikely to gain consent from all parties”.

2) Contrast too HES’ assessment that the visual impact of wire netting across the rockface to catch rockfall would be “high/very high” in what it describes as a “unique and iconic landscape” with its claim that ” Option 1 a permanent closure of the Radical Road footpath would ……………… allow Salisbury Crags to remain fundamentally unchanged, preserving the fabric and iconic setting within gates and high barriers”.

This warped logic appears driven by money: the Options Appraisal shows that attempting to exclude the public by means of a permanent fence is by far the cheapest option.

HES understanding of the Health and Safety at Work and Occupiers Liability Acts

Page 6 of the Options Appraisal sets out what purports to be a statement of the HES’ legal duties in respect of managing the risks from potential rockfalls above the Radical Road. This is wrong on several counts:

First, the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, as it name implies, applies to work and workplaces and to the general public as far as they are affected by this. It does not apply to the hazards of nature or the natural environment. The Act does apply to the countryside when it is used as a workplace – whether this is farming, deer stalking or mountain guiding (so spraying pesticides over people walking across a field would be an offence) – but there is no duty on the John Muir Trust, as owners of the summit of Ben Nevi, to make make it safe for visitors.

And rightly so. Applying the Health and Safety at Work Act to the natural environment would be totally unfair to landowners and in all likelihood destroy outdoor recreation as we know it.

HES’ Options Appraisal appears to have deliberately confused the difference between their duty under health and safety law to protect the public from the risks posed by work related activities in the countryside – including the “de-scaling” work on sections of Salisbury Crags – with the risks posed by natural hazards. The logical incoherence of HES’s position is illustrated by the fact that while the Options Appraisal looks at the risk of someone on the Radical Road being hit by rockfall, it fails to consider the risks posed to someone standing on the top of Salisbury Crags when those same rocks collapse beneath their feet.

Despite this, their Options Appraisal states that if they don’t take “adequate action” there is a risk of “criminal action being brought against HES [under the Health and Safety at Work Act] and/or possibly against staff with potentially significant financial penalties“. In the absence of an opinion from the Health and Safety Executive, who are responsible for enforcing the Health and Safety at Work Act, this is just scaremongering.

Second, HES misrepresents what the Occupiers Liability (Scotland) Act 1960 (see here), a very concise piece of legislation, omits a key clause:

“Nothing in the foregoing provisions of this Act shall be held to impose on an occupier any obligation to a person entering on his premises in respect of risks which that person has willingly accepted as his; and any question whether a risk was so accepted shall be decided on the same principles as in other cases in which one person owes to another a duty to show care.”

If someone climbs a mountain they are generally deemed to have willingly accepted the risks of doing so. This is why landowners are NOT held liable for the many accidents that take place in Scotland’s mountains each year. It is what makes access rights possible. Without it landowners would have to make mountains safe, an impossible task. Holyrood Park is no different, by its nature it is somewhere that is impossible to make entirely safe.

Access rights and risks

During the debates leading up to the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 there was extensive discussion in the Scottish Parliament’s Justice 2 Committee about the potential repercussions that giving people a legal right to enjoy risky activities and go to risky places would have on landowners liability.

As Ross Finnie, the Scottish Government minister response, pointed out when giving evidence to the Committee (see here for transcript):

“Section 5(2) of the bill states: “The extent of the duty of care owed by an occupier of land to another person present on the land is not affected by this Part of this Act or by its operation.”

Mr Finnie went on to say in response to another question:

“I do not think that the number of persons is the issue. What exists is a fundamental duty of care. The number of persons accessing the land will not multiply that duty of care. The duty of care that a landowner owes under the Occupiers’ Liability (Scotland) Act 1960 remains whether the number of persons involved is one or 1,000. The argument that you put forward is incorrect in law.

What this means that HES assessment in the options appraisal that “the increased frequency and greater size of rockfall events, together with the increasing volume of visitors, is now assessed as presenting increased higher risk“ is completely irrelevant to questions of their liability in the event of someone being injured by rockfall. They have therefore got the law on occupiers’ liability totally wrong.

At the event that was held at the Scottish Parliament to celebrate the Land Reform Bill becoming law, I remember asking Pauline McNeill MSP, who had convened the Justice 2 Committee, about what would happen if the Courts started to change their interpretation of the Owners Liability Scotland Act as a consequence of access rights. For example, what would happen if they started finding landowners liable for risks that people up till then had willingly accepted. Ms McNeill’s response was that if that happened, the Scottish Parliament should need to amend the law to protect landowners, not restrict access rights.

In the nineteen years since the legislation has been passed, there has been no need to do because the law on liability remains appropriately balanced between the responsibilities of owners and visitors. Scottish Natural Heritage, as it then was, commissioned Aberdeen University to produce a “A Brief Guide to Occupiers Legal Liabilities in Scotland in relation to Public Outdoor Access” (see here) which includes court cases up till 2016. The guide shows that generally the courts have accepted people go to the countryside at their own risk but that landowners need to take “reasonable care” under the Occupiers Liability Act and any actions that might be required of landowners under the Health and Safety at Work Act need to be reasonably practical.

To illustrate this it is worth quoting from the summary of a key case, Tomlinson v Congleton Borough Council – House of Lords 2003:

“Lord Hutton, having considered a number of the earlier authorities including Scottish authorities, said that: “they express a principle which is still valid today, namely, that it is contrary to common sense, and therefore not sound law, to expect an occupier to provide protection against an obvious danger arising on his land arising from a natural feature such as a lake or a cliff and to impose a duty on him to do so”.

He added that there might be ‘exceptional’ cases where this principle should not apply and a claimant might be able to establish that the risk arising from some natural feature on the land was such that the that the occupier might reasonably be expected to offer him some protection against it – for example, where there was a very narrow and slippery path with a camber beside the edge of a cliff from which a number of persons had fallen. The emphasis is on such cases being exceptional, however.

Because this is a ruling of the House of Lords, the judgement in this case carries particular weight in relation to other similar circumstances.”

That common sense expressed by the Courts is what makes access rights possible. In failing to understand this – or it seems seek any legal opinion – HES have not just unlawfully blocked a right of way, they are giving totally the wrong message to other landowners about how to manage access rights. That makes it particularly important their hamfisted closure of the Radical Rd is challenged – this is a national access issue.

What are the solutions to the risks posed by falling rocks along the Radical Road?

If you read the summaries of the statutory law and the cases quoted in the Brief Guide to Owner’s Liability it should be quickly apparent that the law is subtle rather than black and white. My reading of the case judgements is that the courts have generally found that landowners should warn people or take action to address specific dangers where these might not be obvious but this action has to be reasonable and does not necessarily require areas to be fenced off.

For example, in Darby v National Trust 2001 the judge found:

“It cannot be the duty of the owner of every stretch of coastline to have notices warning of the dangers of swimming in the sea. If it were so, the coastline would be littered with notices in places other than those where there are known to be special dangers which are not obvious.”

While in Bowen and others v National Trust 2011, which involved a 10-year-old boy killed by a falling tree branch, the High Court in London found that the Trust’s arrangements for dealing with this risk, inspections by skilled and competent persons once every two years, was reasonable and the Trust could not have been expected to prevent all risks. Accidents happen.

If you apply this sort of thinking to the Radical Rd, part of what HES had been doing up until they closed it in September 2018 (see here) was on the right lines. They had been taking action, through regular inspections of the crags and descaling where required, to mitigate the risk of rockfall that might not be obvious to the public. While you would not expect a landowner in the wider countryside to do this, it would be reasonable to expect the owner of a city park to do so. They could, however, probably have done more to warn the public of the residual risks of being hit by a falling rock since the degree of risk is not obvious (unlike the risk of standing on a cliff edge). Such action would have been in line with the “volenti not fit injuria” principle which means that if a person knowingly participates in a risky activity – in this case walking below a crag with a known risk of rockfall – they would be taken to have accepted the risks of injury if involved in an accident.

Unfortunately, however, it appears after the 2018 rockfall the bureaucrats panicked, terrified that the public and politicians would blame them for any accident, and used the extraordinary powers available to them under the Holyrood Park regulations to close the Radical Rd without any consultation.

The solution, I believe, lies in the arrangements created by the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 to manage access rights, which sets out duties of both landowners and recreational visitors. Under that Act statutory Local Access Forums have a duty to advise and find solutions to access issues and can seek advice from the National Access Forum when required. Those bodies could advise HES about what measures it might be reasonable for them to put in place to manage risks on the Radical Road while respecting access rights. Had they or other organisations involved in managing access rights been asked, I would have anticipated a fair amount of debate to take place about the wording and size of any signage that might reasonably be required to make anyone thinking of walking the Radical Rd aware of the risks and to make their own decision about whether to walk it or not.

Such a solution, however, based around collective responsibility and decision making, remains impossible so long as the Holyrood Park Regulations effectively exempt it and HES from access rights. The Park regulations (see here) don’t just give HES disproportionate and outdated powers, they also hand HES the entire burden of responsibility for taking decisions about risks and access. Given that burden, It is not that surprising HES panicked.

What is now needed is for HES to join with recreational and amenity interests and call for the Scottish Parliament to amend the Holyrood Park regulations and bring these into line with the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. This would provide an opportunity for the Scottish Parliament – Pauline McNeill is still an MSP and I expect would still be interested – to consider whether anything has changed since they considered the issues of owners liability 20 years ago and whether a reasonable solution, such as I have set out here, can be found within the framework offered by access rights.

2 Comments on “The proposed closure of the Radical Road – Historic Environment Scotland’s misunderstanding of access rights”