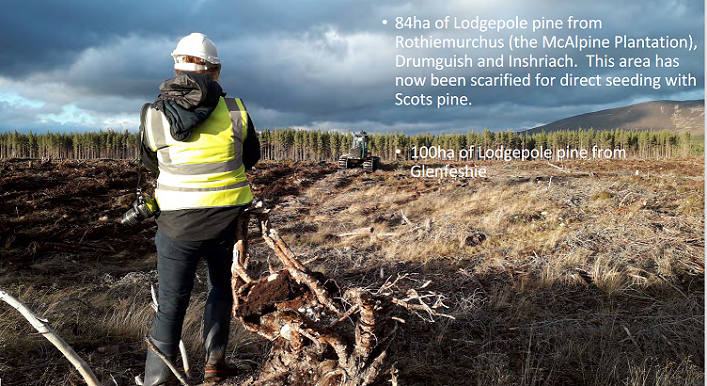

On Sunday I was on Speyside, had 40 minutes to spare and decided to go for a run from the outflow of Loch Morlich to have a look at the work that is being done in the McAlpine plantation by Forest and Land Scotland (FLS) as part of Cairngorms Connect:

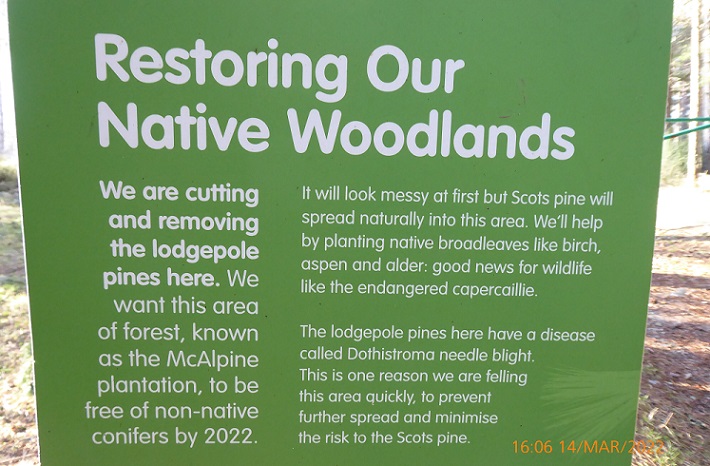

Not far along the track from Loch Morlich, where it forks, there were the usual warning signs about forest operations as well as information about what FLS is doing:

The intention of this work is good, even if it had been prompted and brought forward from 2022-26 by the threat of disease which now threatens all forest mono-cultures.

The restoration work that first comes into sight along the Lairig Ghru track appears to have been done sympathetically and is not dissimilar to the photo in the Cairngorms Connect slide:

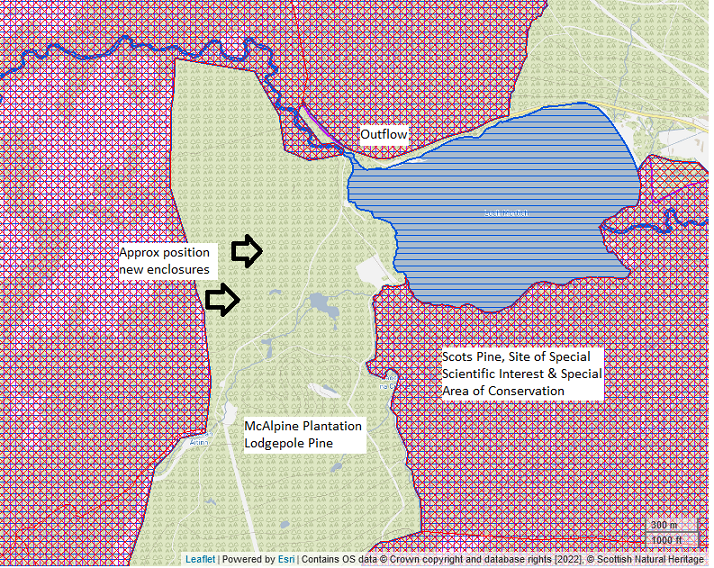

Shortly afterwards I spotted new fenced enclosures set back from the track and went over to have a look:

That this has been allowed to happen not just in the Cairngorms National Park but in the Cairngorms Connect area should be a cause of major public concern.

A little history

The area covered by the McAlpine plantation was once Caledonian forest but was consumed by a large fire which burned from the 3rd – 11th June 1960 (see here). My understanding is that Colonel Grant, the then owner of the Rothiemurchus estate, had initially wanted to let the forest regenerate naturally but was then forced by the Forestry Commission (FC), as was their usual practice at the time, to re-plant it with non-native lodgepole pine.

In 2013 FLS, FC’s successor, agreed a 99 year lease with the Rothiemurchus Estate for the McAlpine plantation. It then converted this into freehold the following year as part of the secretly negotiated deal in which Scottish Ministers bought Rothiemurchus Estate for £7.2m (see here). While it is poetic – or should that be environmental? – justice that FLS are now having to address problems caused by their predecessor on this bit of Rothiemurchus, financially they appear to have bought a liability not an asset.

What has gone wrong?

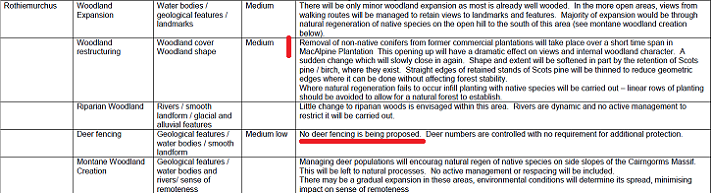

In April 2021 FLS consulted on its draft land management plan for Strath Spey which it then submitted to Scottish Forestry, the regulator, in September (see here). There is a section in the plan about Rothiemurchus which contains a reference to the removal of the McAlpine plantation:

As well as being inconsistent with the FLS plan, the deer fencing presents a direct threat to the capercaillie which the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) is trying to save from extinction for the second time. While wooden batons are better than plastic marking and both help reduce the number of capercaillie garotting themselves on fences, the surest way to protect capercaillie is to avoid fencing entirely. The removal of the McAlpine plantation should have presented an opportunity to extend capercaillie habitat but instead has created another death trap. It is easier, however, for the CNPA to blame outdoor recreation for the decline of capercaillie than challenge FLS.

Part of the explanation for the enclosure may lie in the paper on Deer Management Information (see here) that forms part of the land-management plan. This reveals FLS are having trouble finding contractors prepared to take on deer management in the forest, including Cairngorms Connect, for the price they are offering. There are also problems because the deer numbers in Glen Einich, which is still owned by Rothiemurchus, are far too high and these descend into the Glenmore Forest in winter. This is undermining the draft Land Management Plan which states:

“Whole Plan- Restocking will be mostly by natural regeneration which will be encouraged through scarification. There will be trials of direct seeding in the MacAlpine plantation and transplanting of Scots pine regeneration in to clearfell sites. Seed source planting of native broadleaves will be undertaken where necessary and these areas will be targeted for deer control to ensure successful establishment.”

It is possible therefore that someone decided that the seeding trials in the McAlpine plantation would not work because of the deer numbers and has resorted to the standard forest practice of planting trees in plastic tree shelters and behind fences:

The use of plastic tree shelters is also contrary to the draft plan which makes no mention of their use but states:

“Where natural regeneration fails to occur infill planting with native species will be carried out – linear rows of planting should be avoided to allow for a natural forest to establish”.

The felling of the McAlpine plantation has been so recent that there has been no time to tell whether Scots pine would re-seed here. Moreover, the planting has been done in linear rows, the opposite to what was specified.

I entered one of the enclosures to take a look at what had been planted and how the trees were doing. There were tiny pine saplings – one year’s growth – in some of the tree shelters but my quick reckoning was that one in three lacked any tree:

Planting trees in plastic shelters is an expensive and not particularly effective way to extend woodland, even before you take account of their carbon impact and the pollution caused by plastic entering the natural environment. FLS was right to announce in January that it had decided to stop using them. Having successfully enabled the native pine woods in Glen More to regenerate naturally for over 40 years without using such shelters, it is stranger that they resorted to them last year. One wonders whether the CNPA and Cairngorms Connect were aware of this and, if so, did they object?

The best explanation I can think of for the use of these rows of tree tubes is that someone decided that any naturally regenerated Scots pine would be likely to be overwhelmed by the regeneration of lodgepole pine and needed to be given a head start.

Seed from lodgepole pine is clearly regenerating naturally both within and outwith the enclosures:

But the answer to this problem is not plastic tree shelters, it is weeding out the non-native species like lodgepole pine that will impact on the ability of the native pine wood to re-establish itself here.

But the answer to this problem is not plastic tree shelters, it is weeding out the non-native species like lodgepole pine that will impact on the ability of the native pine wood to re-establish itself here.

Weeding, however, requires money and the employment of a local forester to keep removing the lodgepole pine for as long as necessary. Unfortunately, there was other evidence to show FLS does not have the funds to manage their land properly: the draft plan contains a map on the ecological value of deadwood (see here) which records the lodgepole in the McAlpine plantation as having low potential. So why leave so much low value deadwood within the enclosures where it will shade out vegetation growth and hinder natural regeneration? The most likely explanation is cost.

Sixty years after the decisions that have caused the current problems in the McAlpine plantation, FLS is making a new set of mistakes. These are likely to have environmental and financial costs far into the future. Instead of treating the Glen More forest like an industrial unit, FLS need to start following the same principles as the more progressive members of Cairngorm Connect otherwise they risk bringing that organisation into disrepute. It’s time the CNPA empowered their staff to intervene.

A good exposure of the continued mistakes being made by FLS. Yes, a large part of the problem will be lack of finances. The other issue which is widespread throughout our public services is the lack of monitoring and enforcement of approved plans by the regulator – in this case Scottish Forestry. The problem is – will anything be done, or will FLS, Scottish Forestry and the Scottish Government which holds the finances just ignore these issues? I know where my opinion lies – but I would love to be proved wrong!

This saga by Loch Morlich demonstrates all that is wrong with Scottish Government forestry policy and practice. There has been an endless series of disastrous government decisions on forestry in this area since the fire in the 1960s. The whole of this area should now be a naturally regenerating part of the Glemore – Rothiemurchus Caledonian Pinewood. All that has been required over the last 50 years is effective deer control, with absolutely no need for fencing and planting of either Scots pine or any other native or exotic species. The past has been a ridiculous and unnecessary expenditure of public money which looks set to continue into the future. Scottish government ministers need to tell their state forestry agencies to stop managing this land as some bizarre form of industrial forest and turn it into a natural forest by getting rid of all the fences, stop planting and disturbing the soils and leave nature to do the rest.

The lodgepole regeneration will need to be removed (by hand pulling or cutting with loppers) before they start seeding irrespective of what method is used to encourage Scots pine and however well the Scots pines grow. That is a separate issue.

The use of very short tubes appears to be to protect Scots pine from deer (and perhaps from voles) for the first few years of life, until the roots are established, and perhaps also for easy identification purposes in case future operatives removing lodgepole cannot rapidly tell the difference. If the pines are not regarded as a commercial crop, then some non-lethal deer browsing of small established trees could be an advantage, in that it can create more bushy and deformed trees that provide a better habitat for other wildlife, as well as creating a more attractive and diverse woodland.

I suspect the deadwood potential of the remaining lodgepole brash is classified as “low” because the main logs have been harvested, so there is not much volume of wood there. Leaving the brash provides a source of some nutrition in future years as the brash decays and can help to protect young trees and the ground vegetation from deer, and at the density shown in your photos will do little to suppress vegetation growth or hinder natural regeneration. The brash inevitably exists: removing it would require more use of fossil fuels and more ground disturbance and compaction if vehicles were used and would result in a huge pile of brash that would either have to be burnt (which destroys the soil beneath the fire) or chipped, both of which would result in yet more carbon being released to the atmosphere.

I agree that the brash should be left in place and allowed to decay, even though some visitors will be upset at the “untidyness” of this ecologically sound process! Also, there is a big job ahead to weed out the regenerating exotics (Lodgepole and other species) both here and elsewhere in Glenmore – the upper slopes of Meall a’ Bhuachaille, for example, could do with some exotic pruning, so that the re-establishing tree-line is dominated instead by native species. It would be far better to spend Forest and Land Scotland money on regular (annual ?) cutting down of the regenerating exotics then wasting it on tree guards and deer fencing in Glenmore.

Can’t imagine the idea is plant plastic and let the deer deal with the lodgepole.

There tree planting policy needs very strong gatekeepers

Especially if its aim is reducing our carbon footprint.

For those without a forestry background (me included) chapter 3 of Birds and Forestry, by Avery and Leslie (published by Poyser in 1990) provides a lot of useful background to the practices of commercial forestry. Most of that chapter (not all) can be read online at – https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Birds_and_Forestry/apv7bV5gqwkC?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover