What the National Trust for Scotland (NTS) have discovered at Mar Lodge

While away in Lochaber last week I read a very interesting article in the latest Reforesting Scotland journal (Issue 64) on ‘Regenerating aspen: “spontaneous appearance” at Mar Lodge Estate’. The author, the ecologist Andrew Painting, recounts how in 2018, while undertaking fieldwork in Glen Quoich, he:

“was surprised to stumble across a tiny grove of aspen seedlings, shyly poking their heads above the heather. What was surprising was that there were no mature aspens in sight. My understanding at that time was that, given how infrequently aspen sets seed in Scotland and how it tends to persist through suckering, the species was particularly poor at recolonising lost ground”.

A couple of weeks later he came across another grove and then another. That prompted a proper survey which then discovered that in the Mar Lodge Regeneration zone, where the deer population is now under 3 per km, there were:

“19 newly regenerating stands of aspen which were often occurring at some distance (generally more than 100m and in some instances over 500m) from mature trees”.

In the Mar Lodge Estate Moorland zone, where the deer population is just under 10 per km, “no “spontaneously appearing” stands were recorded,” despite this area have a higher number of mature aspen trees (315 as opposed to 212).

The evidence is clear clear. If you reduce the number of grazing animals, native woodland will recover and in unexpected ways.

The implications for tree planting

This wonderful news from the National Trust for Scotland poses a significant challenge to the prevailing view that if we want nature to recover, the best thing we can do is plant trees.

While a number of conservation landowners are now retreating from that view, led by the example of Glen Feshie where, as a result of a sustained reduction in deer numbers, trees are now “sprinting up the hillsides”, most still maintain there is a need to plant scarce species like aspen. The question that these people have failed to ask is how aspen and other rare species like the montane willows colonised Scotland in the first place, which brings me to the aspen I saw last week in Lochaber.

This small stand of aspen is very isolated, the nearest aspen we saw was over three kilometres away. The first photo illustrates the main reason why it has survived here, it’s located on the side of small gorge out of the reach of grazing animals, though quite how the vertical branches on the nearside managed to escape hungry mouths after the large tree fell across the gorge is something of a mystery.

The more difficult question, however, is to explain how did the aspen, which has developed into a small stand through suckering, get here? The orthodoxy, which Andrew Painting admits he believed until he saw the evidence of his own eyes at Mar Lodge, is that because aspen seed is produced so infrequently in Scotland (less than once in ten years) and now replicate mainly through suckers, that planting is needed to conserve the tree and the host of rare invertebrates which depend on it. The trouble with that tree planting orthodoxy is its incapable of explaining HOW aspen colonised Scotland, including remote corners such as that pictured above, after the ice ages.

Perhaps seeding once every ten years was sufficient for aspen to spread? Perhaps birds and animals inadvertently helped carry the seeds to new ground? Or perhaps the suckering roots extend far far further than anyone has imagined and if grazing pressures reduced – aspen is favoured by herbivores and the food of choice for beavers – it would pop up all over the glen below the stand in the photo? I can offer no definitive answer and nor did Andrew Painting in his article. He, being a good scientist, recommends further research to try and establish whether the new stands were established through seeding or have developed from hidden root systems. Whatever the answer, aspen have far more regenerative capacity and ability to colonise the land than anyone thought.

This doesn’t mean that there is no longer a need for the tree nurseries that are growing aspen in Scotland to stop doing so. But it does mean that we should be thinking very carefully about where we plant and should avoid doing so in places like Scotland’s National Nature Reserves, Mar Lodge Estate included, whose purpose is to provide places where nature can evolve with minimum human interference.

The current position at Mar Lodge

In 2017, before they discovered the “spontaneous” natural regeneration, NTS planted 2,500 aspen in the “moorland zone” along the River Dee as part of the “Pearls in Peril Project” (see here). What’s happened shows that wouldn’t have been necessary if they reduced deer numbers further in the Moorland zone.

There appear to be elements of the tree planting orthodoxy that still survive among staff at NTS. Having decided that aspen needed minimal further “conservation action”, Andrew Painting’s article describes how NTS still decided to plant 10 plots of 100 aspen between stands in the regeneration zone to see if this would help them join up. But in an excellent blog post in February (see here) the Mar Lodge senior ecologist, Shaila Rao, explained how natural regeneration has been working and how NTS are now only planning to plant two species of montane willow.

In my view, NTS staff should be a bit more patient and allow time to see if the downy and whortle leaved willows start, like aspen, to pop up “spontaneously” as deer numbers reduce. But the direction of travel at Mar Lodge, to move away from planting and let nature do the job, is both clear and welcome.

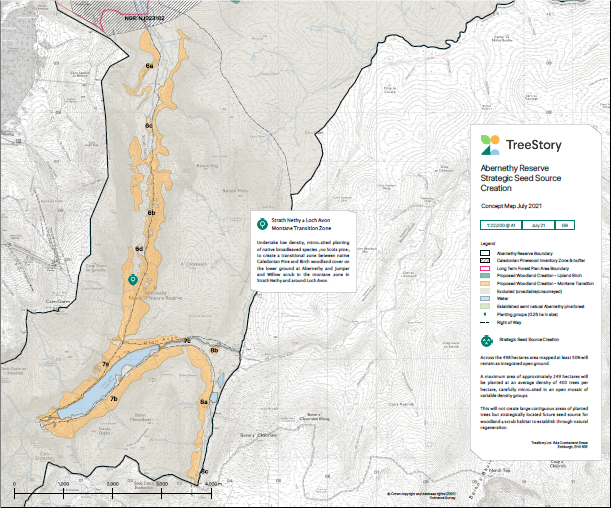

The RPSB’s plans to plant the Loch Avon basin

Unfortunately, just over the watershed in the Glen Avon basin, the RSPB have started to plant “missing” deciduous trees in another National Nature Reserve and the Wild Land Area at the heart of the National Park.

In June they enlisted 30 well-intentioned volunteers (see here) to carry saplings in over the hill for an extensive planting project in an area where soils have been undisturbed for millenia:

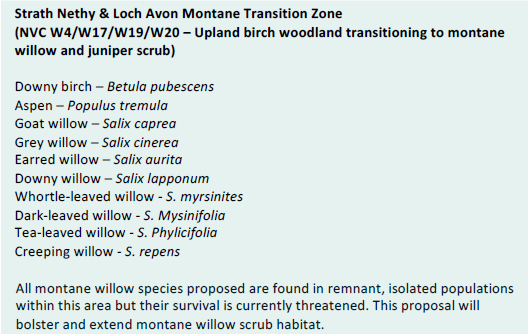

Besides the two montane willows NTS are still planting, the RSPB’s plans include a host of other species including aspen:

The example of Mar Lodge demonstrates that much, if not all, of the planting that the RSPB have started in the Loch Avon basin (and Strath Nethy) is not necessary, let alone desirable. What they should be doing is bringing the deer numbers in the River Avon catchment down and then letting nature takes it course.

The RSPB as kind enough to consult me about their tree planting plans in the summer (I lodged an objection which I will come back to). I am still in dialogue with them and am still hopeful that they can be persuaded to change direction but believe it is time the issues were made public.

Rather than planting trees I think it would be more appropriate for the RSPB to research further the role that birds play in native woodland expansion in Scotland. That is widely appreciated in other parts of the world, but less so in Britain.

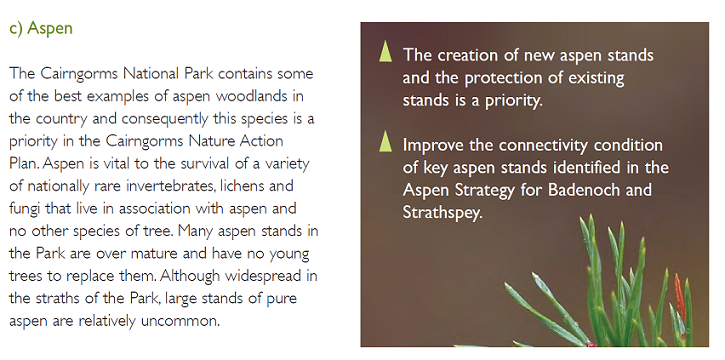

The Cairngorms National Park Authority, aspen and natural regeneration

In 2001 the Cairngorms Partnership, the predecessor of the National Park Authority, and the RSPB held a conference on aspen. The proceedings (see here) include a number of very interesting papers including one (P74) on the aspen at Invertromie on RSPB’s Insh Marshes Nature Reserve.The paper reported that although the RSPB had excluded sheep from the wood, aspen was still failing to regenerate because of grazing by rabbits and roe deer. The challenge for aspen, more than any other tree, is it is so palatable to herbivores. The corollary of this, however, is that if grazing animals are at levels that allow aspen to regenerate, then all our other native tree species should be able to do so too.

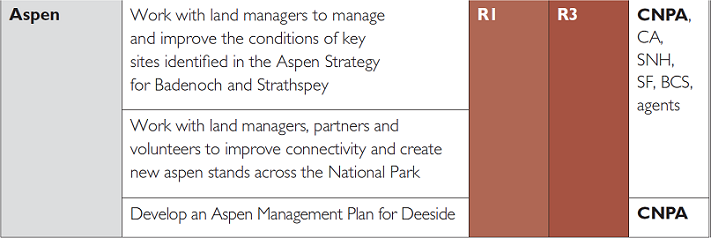

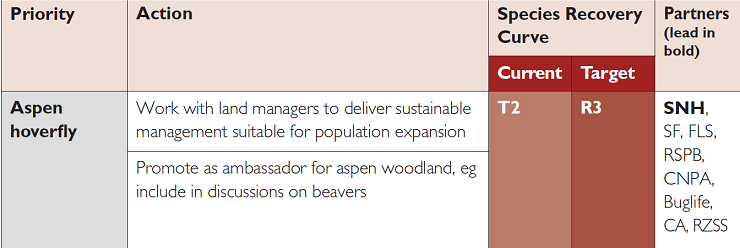

The Cairngorms National Park Authority has since it was formed, led a number of initiatives to conserve aspen. Currently, there are a plethora of plans and targets to conserve aspen and the species that depend on it, for example:

It would be interesting to know if ANY of these plans have done anything to help aspen extend its range and protect the species that depend on it. I am fairly confident, however, that the reduction of deer numbers in the Mar Lodge conservation zone, which was NOT in any of the aspen management plans, will have made far more difference than anything these plans have achieved.

The lesson for the Cairngorm National Park Authority (CNPA) and other conservation organisations is that if we bring down the number of grazing animals, nature will recover, and there will be no need for targetted management interventions, whether these are for breeding rare insects or planting “missing” trees.

But that means taking on the sporting estates in the Cairngorms, it would mean the RSPB taking on the owner of the Glen Avon estate, whose deer comes over into Abernethy and impact on the natural regeneration there, and it would mean the Cairngorms National Park Authority tackling the deer issue.

Deer, natural regeneration and the National Park Partnership Plan

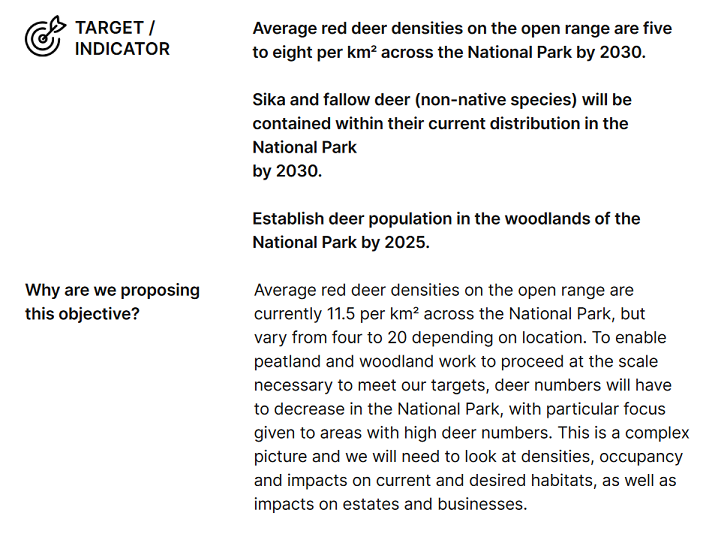

The draft Cairngorms National Park Partnership Plan (NPPP), currently out for consultation (see here), shows that while the CNPA is moving slowly in the right direction on deer numbers, it is not nearly far enough:

A deer density of 5-8, while an improvement on the usual 10 deer per square kilometre target favoured by NatureScot, the organisation responsible for overseeing the management of deer in Scotland, is still hopeless from a conservation and climate change perspective.

During the period that NTS were aiming for five deer per square km in their regeneration zone, natural regeneration was so slow as to make little appreciable difference. Now that they have reduced deer to levels to 3 per square km, not that much greater than in Glen Feshie, aspen, pine and a host of other species are popping their heads above the heather. The CNPA needs to explain why it has ignored this evidence in setting its targets.

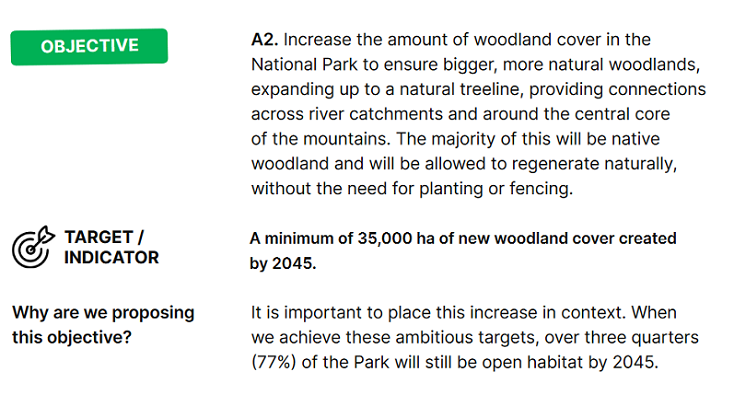

The woodland expansion section in the draft NPPP indirectly provides confirmation that the targets for numbers of red deer are still far too high:

While the emphasis on natural regeneration rather than planting is welcome, the aspiration of this landowner dominated National Park is that by 2045 (what emergency?) just 23% of the Cairngorms will be covered by trees. That is still way below the 38% average tree cover in the European Union in 2015 (see here). And the Cairngorms is meant to be a National Park…………….

While I will consider the CNPA’s draft National Park Partnership Plan in more detail over the next couple of months, it only needs to contain two main actions to address the climate and environmental crises:

- reduce deer numbers to an average of 2 per square kilometre across the National Park by 2025, and

- end all muirburn now.

Nature will then do the rest (and we won’t have to worry about raptor persecution any longer because all the traditional sporting estates will have shut up shop allowing new green jobs to be developed).

Nick asks how “aspen colonised Scotland, including remote corners … after the ice ages.” Studies on the genetics of aspen in Scotland indicate that extant populations originated, post-glacially, from a freely sexually reproducing population, but which have since survived chiefly by vegetative propagation. Seeding, and establishment of new stands of aspens by seeding, does appear to be rare today, but that was not the case in the distant past.

The report of “a tiny grove of aspen seedlings, shyly poking their heads above the heather. What was surprising was that there were no mature aspens in sight”, most probably refers to suckers (not seedlings), previously suppressed by grazing but (just) able to survive.

As far as the rarer upland and montane willows are concerned, like all willows they have separate male and female bushes, and are out-breeding, mainly reproducing by seed. Some remnant populations on the Scottish hills are single sex and doomed to eventual extinction unless plants of the opposite sex are introduced nearby.

Certainly when it comes to natural regeneration of trees and shrubs on Scottish hills, patience is a virtue, and the impatience of managers and funders, needs to be guarded against. It does take a reasonable period of time, with sufficiently reduced grazing pressure, before a reliable assessment can be made of what species are found where, and where and how quickly natural regeneration is occurring. Perhaps 20 years might be a good rule of thumb?

Nick writes “The lesson for the Cairngorm National Park Authority (CNPA) and other conservation organisations is that if we bring down the number of grazing animals, nature will recover, and there will be no need for targeted management interventions, whether these are for breeding rare insects or planting “missing” trees”. Within sufficiently large areas of land managed for nature, that may well be the case, in time. However, some interventions are well justified as “first-aid” measures to ensure a species or population survives. There is a view that, as Nick writes, the purpose of places like Scotland’s National Nature Reserves is to “provide places where nature can evolve with minimum human interference”. Refraining from management interventions is almost always a good idea to begin with, but is not always desirable in the longer term once evidence has been gathered. And it depends if we, as a society, have a vision for the habitats and species in an area, or if we are content to let nature take its course. The latter view is increasingly advocated, but perhaps naively, overlooking the fact that some species and habitats we value may in turn be lost or never reach their potential.

Adam Watson published a paper in 1977 on “Wildlife potential in the Cairngorms region”, In, Scottish Birds Vol. 9, Number 5, Spring 1977, pp. 245-261, available at – https://www.the-soc.org.uk/files/docs/about-us/publications/scottish-birds/sb-vol09-no05.pdf. In this paper he wrote “The forests of Scots Pine and birches in the Cairngorms, although fine and rich in wildlife compared with most other, wholly artificial, northern woodlands in Scotland, are only degraded remnants of what could be there” (page 256). In the section on “What is needed to realize the potential for wildlife conservation” he wrote, “Time is short, as many trees are ancient, especially on Mar, and are dying fast. A big problem is whether areas should be left alone (apart from excluding deer) or whether regeneration should be hastened by burning, planting existing species and introducing species like Aspen and Rowan that are native but may be absent from the site. As many boreal forests in other countries are dynamic and change even at the same site through time, there is a case for interfering and speeding up the change, at least in some places. As a safeguard, a high proportion of the most valuable areas should be left to change naturally after reducing the deer. (page 260).

Adam’s 1977 paper does reflect the time when it was written, and is interesting for that reason. But he was clearly not averse to management intervention, as long as it was justified, targeted and proportionate.

Thanks Andy for the very informed and informative comment – readers should know that much of the credit for the 2001 conference on aspen was down to you and I hope your comment will encourage interested people to take a look at the conference proceedings.

It seems to me the key ecological question is the extent to which the apparent change in the way aspen reproduce from seeding to vegetative reproduction is down to climate change or to grazing pressure or what mixture of the two. I don’t see why in principle, even if aspen do only seed occasionally, they shouldn’t recolonise the land BUT if evidence showed that is wrong, the conclusion surely should be that aspen are no longer suited to our climate and we should stop trying to fight against nature. I am more optimistic than that. It seems to me that IF grazing pressure is reduced to the extent that larger stands of aspen are allowed to develop, as at Mar Lodge, there may be more mixed stands than anyone guessed and, as those develop, in time there may be more seeding.

I think your point about waiting 20 years and then potentially planting some “missing” trees is reasonable BUT only so long as grazing pressure is radically reduced to around 2 deer per square km for that period. On Mar Lodge therefore it would be reasonable to wait say another 15 years before any further interventions. The evidence from Glen Feshie – which has not yet reached that 20 year mark – is that some of these montane species that people were concerned about are now making a come back.

Adam Watson was a brilliant scientist and while his 1977 paper, as you say, was a product of the time I don’t think it contradicts what my post argued. While he was always very strong on the need to tackle overgrazing, that paper was written well before there was evidence in Scotland for what happened when deer numbers were reduced to low numbers. Adam placed a huge value on undisturbed soils, eg arguing strongly against the use of heavy forestry machinery in the Caledonian pinewoods because of their impact, and it was because of that in the article he said some areas should be left to nature. Those areas included the core of the Cairngorms I know Adam was very very concerned about RSPB’s proposals to plant in Abernethy as a consequence. I am reasonably confident that now he would have agreed with you, wait at least 20 years and in some areas perhaps we should just wait and see what happens!

In my previous reply I wrote:

“Studies on the genetics of aspen in Scotland indicate that extant populations originated, post-glacially, from a freely sexually reproducing population, but which have since survived chiefly by vegetative propagation. Seeding, and establishment of new stands of aspens by seeding, does appear to be rare today, but that was not the case in the distant past.”

While, I think that statement is correct, it should be stressed that in some years aspen tree do seed prolifically. Vegetation reproduction of aspen , to form single sex clones of trees, is so obvious, that occasional establishment from seed might be overlooked. In Scotland there was mass flowering of aspens in 1996 and 2019.

I was pleased to find a few aspen in Glen Coe by the meeting of the waters recently and wondered where it could have come from. Fairly closed off to deer down there though. I shall be looking more intently next time I’m wandering

I spotted that distinctive yellow on the southern flank of the Aonach Eagach while driving past a week ago. There is still rather too much grazing in Glen Coe and I don’t know what surveys NTS has done but I suspect it may be another of their properties where aspen might be more widespread than has previously been suspected.

The scarce distribution of aspen can be puzzling in some ways but part of the cause may be that it seems to be that it is particularly attractive to grazers. I recall in the USA Rangers telling me that wolf dens of long standing could sometimes be spotted by the growth of aspen around them as herbivores naturally avoided such areas. I was never able to confirm this on the ground.

Also, I recall American studies that demonstrated that aspen roots could remain dormant in the ground for 40 years. I recall also that studies of small pines just cm high in the northern corries of the Cairngorms showed they could be 30 years old. Presumably small dwarf growths of aspen could be of similar age or even much more. I stayed on holiday with my wife in the Austrian alps with a family that was now into tourist accommodation but which had farmed that land for centuries with livestock browsing widely. I noted the absence of aspen which I thought would grow there as an indigenous species and asked the young farmer about it. He assured me that there had never been aspen there. The next day, my wife and I went uphill for a walk and, on the way back down, I saw and odd small twiggy growth down between some rocks. You can guess what it was.

I am surprised that the so-called environmentalists are not demanding aspens should be cut down as they are not a native species [THIS IS NOT TRUE SEE BELOW ED]. How can anyone define what is a native species? when we have been under thousands of years of ice. Our national park has been searching for Beech trees to cut down as they don’t fall into the definition of native and are not ecologically correct.

I am afraid you have the first part of this wrong, aspen arrived in Scotland 10,000 years ago and are therefore “native” under any definition of that term . Beech arrived much later – that is not to justify their destruction on Inchtavannach by Nature Scot