Following my two posts on BrewDog’s proposals to create a Lost Forest (see here) and (here) at Kinrara, plans for peat bog restoration on the estate appeared on Highland Council’s planning portal (see here). In April the Scottish Government issued new planning guidance on Permitted Development Rights (see here) which required peat bog restoration schemes to be notified to the Planning Authority under the Prior Notification Scheme (like Forestry and Agricultural tracks (see here)). While this new requirement appears to have been prompted by a wish to encourage private markets to invest in carbon capture – by assuring investors that they are not investing in a dud – it is welcome as introducing a degree of transparency to peat bog restoration schemes that has not existed up until now.

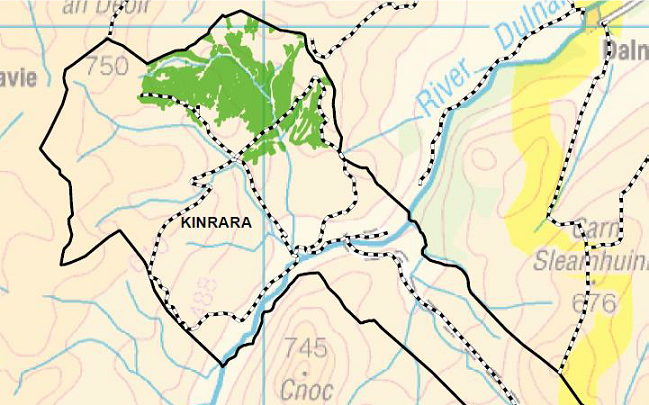

The Kinrara scheme is one of five notified for the Monadhliath by Strath Caulaidh, an environmental consultancy that undertakes peat bog restoration on behalf of NatureScot. Almost all of the latest proposals are outwith the Cairngorms National Park boundary and the proposed restoration work for Kinrara is on the north-west corner of the estate.

From comparing the maps of the peat bog restoration with Scottish Woodlands plans to plant a new forest at Kinrara, there appears to be a small but significant area of overlap:

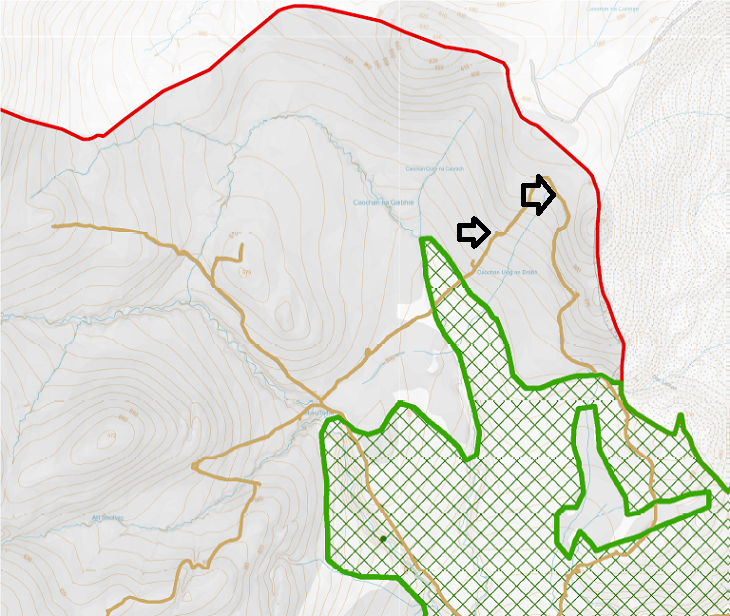

The “finger” of woodland restoration alongside the burn, the Caochan na Gaibhre, on either side of the hill track is marked on the Strath Caulaidh map as being an area of proposed peat bog restoration. It should not be both. It could result in NatureScot forking out money to restore peat, while Forestry Scotland fork out other public funds to plant it!

In my posts on the Lost Forest I argued that BrewDog should have produced a single landscape plan, rather than a forest plan. Strath Caulaidh proposals shows I was right. It appears there are two sets of consultants progressing plans without any communication between them BrewDog clearly needs to get a grip!

Another type of grip, the moor grips shown on the Strath Caulaidh map, are scarcely visible on the ground. I did not realise there were so many when cycling by in July. The damage down by muirburn is far more obvious the casual observer. The moor grips were, however, were visible from the top of the track looking back:

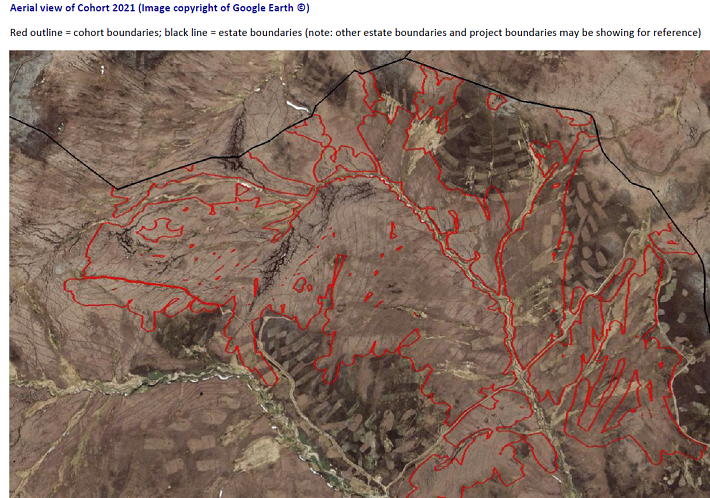

The moor grips – and the extent of the damage done by muirburn – is easier to see from the Google Earth map contained in Strath Caulaidh’s Prior Notification:

Clearly in the past a serious attempt was made to drain the bog here. One wonders how much of it was paid for by public money?

Given that the drainage ditches are not obvious on the ground, it is valid to ask how far they are still damaging the peat bog? There was very little sign of exposed peat along the drainage lines and it appears the grips may have filled in with vegetation. I am been informed, however, by Stephen Corcorran – the Cairngorms National Park Authority’s Peatland Officer and a real professional – that people working on peat bog restoration in the Cairngorms have done tests and found that beneath apparently re-vegetated ditches the water may still be flowing. Though concealed, old ditches therefore may still be serving to erode and dry out the bog.

Unfortunately, the Prior Notification does not say whether that is happening in the catching of the Caochan na Gaibhre, the land featured in these photos. The peat bog restoration work seems to have been planned on the basis of what google earth shows, rather than any survey on the ground. If surveys showed the ditches are still draining the bog, work to block them up might be justifiable.

There is certainly some “spare” peat and vegetation, used in the construction of grouse butts, which could be used to fill in ditches, now that driven grouse shooting has stopped on the estate. There is no mention, however, in the plans of whether it’s intended to restore the butts or whether driving a digger over the bog to remove them or to fill in the ditches might cause more damage than it prevents. These are difficult questions but ones which need to be answered if we are to ensure peat bog restoration schemes are worth it.

The evidence is clear, however, about what development has done most damage to the bog:

The hill track – used to transport grouse shooters and make intensive management of the moor easier – acts as one enormous drainage line which has been driven through the bog. Etraordinarily, there is no mention of this in the Prior Notification:and no plans to remove it. Why not?

The answer, almost certainly, is that peat bog restoration to date has been driven by the interests of landowners and they have not been prepared to see damaging developments, like hill tracks, removed. If BrewDog is really serious about the need to create carbon sinks on its land at Kinrara, therefore, it should be starting with plans on how to restore the track. Incidentally, one of the reasons Strath Caulaidh may not have included proposals to do this in their plans – despite the change in landowner – is these tracks, which are so damaging to peat and the landscape, make it much easier to drive diggers up the hill!

Strangely, an area of obviously damaged bog is not included in the restoration plans. Perhaps that is because it is hard to see on google maps?

Other than alongside the track, the main area of exposed peat on the bog is along the Caochan na Gaibhre and this appears perfectly natural:

To the lay person, this is not a peat bog where restoration work is obviously required – apart from the track. In view of this, Highland Council should be asking Strath Caulaidh and BrewDog to demonstrate that the proposals will have a net carbon benefit..

Red Deer

The Strath Caulaidh plans do, however, contain some very useful information on red deer numbers.

These statistics show that there has been a significant reduction in deer numbers in the Monadhliath in the last fifteen years. But we now know that the benchmark of 10 deer per square kilometre is far too high to allow successful natural regeneration of trees to take place. For that, numbers need to be reduced to less than five deer per square kilometre, depending on habitat. That is why Scottish Woodlands are wanting to “protect” their proposed “Lost Forest” at Kinrara with deer fencing. As I argued in my previous posts, this provides evidence of why BrewDog needs to get a grip and bring deer numbers down.

Whether Strath Caulaidh are right to assert in the Prior Notification that at present there is little evidence that deer densities of 10 per square kilometre do little damage to peat bog restoration remains to be seen. I hope to consider those issues in a further post but meantime there is a strong argument that BrewDog should not risk this and adopt the precautionary principle. . Further reduction in deer numbers would help guarantee that any public money spent on peat bog restoration was not wasted and would enable BrewDog to develop woodland through natural regeneration.