If BrewDog’s description of Kinrara as a “Lost Forest” is appropriate for the Strathspey part of the estate (see here), it feels even more apt as you descend the Burma Rd past scattered pine trees towards the River Dulnain.

But then, after you cross the Allt nam Muireach, you realise the pines are not so lost after all:

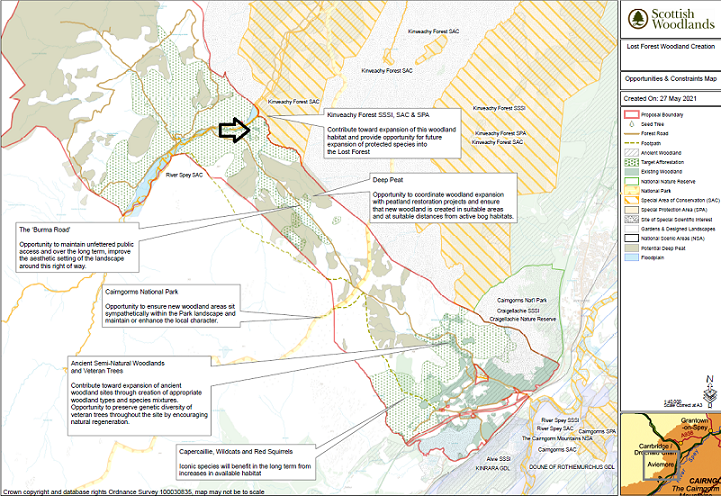

The “Opportunities and Constraint” map from the Scottish Woodlands consultation on creating a new forest (see here) shows the relationship quite well:

The pine trees are right next door to the Kinveachy Special Area of Conservation, created to protect and regenerate the large fragment of Caledonian Pine Forest along the River Dulnain above Carrbridge. It seems strange that the Kinrara pines were never included in the SAC, but then the Dulnain part of the Kinveachy SAC was originally included within the proposed Cairngorms National Park boundary. Conservation boundaries owe as much to politics as to science!

The view from the Kinveachy side shows how in ecological terms this should be treated as a single forest. The good news is, after extensive efforts to reduce deer numbers, the Kinveachy Caledonian pine forest is now regenerating up the Dulnain to the boundary with Kinrara.

But at the Kinveachy boundary, unprotected and facing owners whose main concern appears to have been how they could increase their bag of grouse, the regenerating forest has up until now been met with a wall of fire. That has acted as a block to the Caledonian Forest expanding to regain something of its former extent and in doing so incorporate the isolated pines.

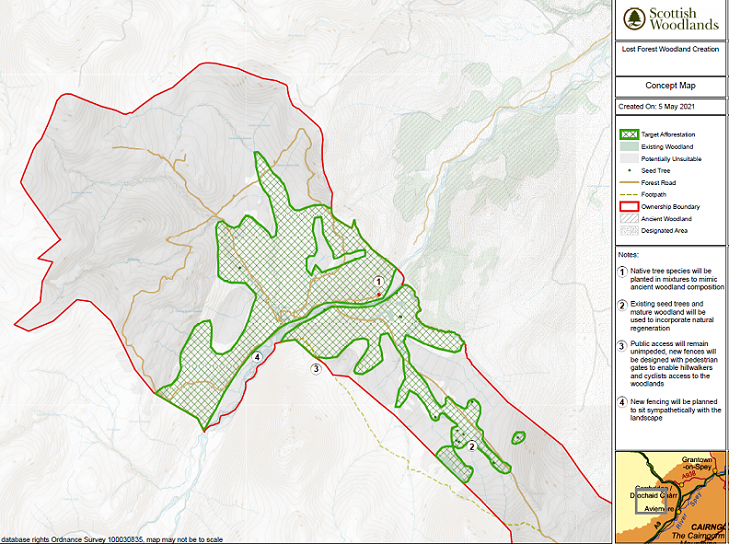

Scottish Woodlands’ proposals for planting and fencing

Following BrewDog’s purchase, with the burning stopped, Scottish Woodlands is now proposing to plant most of the lower lying land and protect the new trees with deer fencing:

The new planting is completely unnecessary because, as on the Strathspey side of the estate, almost anywhere you care to look outside of peaty areas, there are trees and shrubs just awaiting their chance:

While at first sight the slopes above the north bank of the Dulnain appear burnt to bits and almost treeless, tucked away and along the burns its a different matter:

The position on the Dulnain side of Kinrara is exactly the same as on the Strathspey side, with muirburn ended, the lost forest is waiting there to regenerate naturally. This means there is no need to plant. Moreover the Dulnain side of Kinrara is also in the Monadhliath Wild Land Area – a fact that Scottish Woodlands fails to mention – which makes fencing even more inappropriate. What BrewDog needs to do therefore to make the Lost Forest a reality is to reduce deer numbers as Wildland Ltd has done in Glen Feshie.

The challenge is actually trickier than in Glen Feshie because of the shape of the Kinrara Estate and its place in the Dulnain catchment. Data from the Monadliath Deer Management Group (see here) shows that over the summer months deer are mainly found above 600m but then in the winter move onto the lower ground and down the Dulnain. That means there are relatively few deer on Kinrara during the summer months and into the stag stalking season, whereas after that season ends grazing pressures increase. A very good illustration of why BrewDog should press the Scottish Government to abolish the closed season for stag stalking, as recommended by the Deer Working Group, and as I suggested in my last post.

Without a reduction in numbers, the creation of fenced exclosures will deprive the deer of winter foraging and force them further down the Dulnain, where they end up in bad weather at present, increasing the grazing pressure on the Kinveachy Caledonian Pine wood. As the current proposal stands, for every new tree Scottish Woodlands plants, a naturally regenerated sapling could be lost lower down. Is this what BrewDog really want? Conversely, if BrewDog joined forces with the Seafield Estate and focussed on reducing the numbers of red deer, for every sapling that regenerated on Kinrara, another might regenerate at Kinveachy.

Other issues with Scottish Woodlands’ proposals for the Dulnain catchment

While once the land on either side of the Burma Rd may have been forest, now a significant proportion of it appears to be peat and there are questions of how far trees will grow in these areas. Scottish Woodlands states that planted areas will avoid deep peat, defined as peat over 50cm in depth, but the opportunities and constraints map (above) shows areas where planting and peat overlap. Instead of asking consultants to work out what areas might be better left as peat bog and what areas should be planted, BrewDog would be better leaving it to nature.

Scottish Woodlands plan says nothing about where peatland restoration might take place, though BrewDog announced they were hoping to do this after they purchased Kinrara. While much of the peat bog I saw was in fairly good condition, the road under Sguman Mor was a shocker: another reason why BrewDog should be producing an overall estate conservation plan and not just a tree planting plan.

And just like on the Strathspey side, Scottish Woodlands’ plan says nothing about montane scrub. Its half a woodland creation plan, only dealing with the lower to middle ground. Fencing that will do nothing to help montane scrub develop. Another reason why BrewDog need to focus on reducing deer numbers to enable natural regeneration rather than planting trees behind fences.

The choice facing BrewDog

Ask people what they think the most important things we should be doing to address the climate and environmental crises and most will probably include planting trees high on their list. Its practical and something everyone can do. That was clearly BrewDog’s intention when they purchased Kinrara.

What most people don’t realise, however, despite all the evidence from Glen Feshie, is that if you reduce the number of grazing animals sufficiently, over much of Scotland trees would come back without any other human intervention. Kinrara, as I hope I have shown in these two posts. is one of those places. It’s also very special because of its lost Caledonian Pine forest. Scottish Woodlands planting proposal threatens not just that, but the regeneration that is taking place at Kinveachy downstream.

The challenge for BrewDog – and any other landowner facing this choice – is that this is not just a matter about choosing what is best for the land. The choice currently has serious financial implications. Unfortunately, the current forestry subsidy system directs money towards planting trees and fencing. Though neither are particularly effective – a significant proportion of deciduous trees that are planted fail to survive while fencing rarely does its job for more than a few years – there is no equivalent support for reducing deer numbers. Only the richest and most committed landowners can make the right choice.

As a completely new type of landowner with a high public profile, BrewDog has the opportunity to persuade the Scottish Government to change all that. In doing so they could do far more for tackling climate change in Scotland than they ever would by planting trees on their own land.

Brilliant! I trust you sent a copy to BrewDog?

Great work again Nick. I do hope powerful people are paying attention to the site. The thoroughness of the research makes me wonder if I have any competence to comment. Some thoughts come to mind. I thought your articles treated Brewdog rather kindly. Are they not a ruthless multinational shown up in recent reports? Are they not in this land game for the government money that is attractive to all those in the market for an estate? Good PR as well,till recently their forte.

Whilst agreeing with the thrust of the deer management and regeneration of woodlands I’m not sure that is everywhere as potent a land improving force. Or in any way sufficient.Would there not locally have been enormous animal populations and more people in the early 19th century without those numbers driving degradation to anything like currently.

Since it’s the out of control atmosphere that is having such an impact on the land including the Parks is it perhaps appropriate to consider attitudes to energy production and storage, tourism, tech interventions in the atmosphere.

I’m just concerned that too many seem to believe trees, peat conservation, deer management etc are on their own a large part of addressing of the situation.

Hi Dick, you are absolutely right, tree planting and peatbog restoration will never even begin to compensate for the fossil fuels we extract from beneath the earth’s surface. Peatbog restoration at Pitmain is the perfect of the farce – the Scottish Government is buy paying to restore peat to lock up small amounts of carbon on land owned by the family of the Chief Executive of the largest private oil company in the world

In terms of grazing animals, my understanding is there were significant differences between the early 19th Century and now. First, in terms of livestock, sheep were much smaller and unable to tolerate the winters outside so were kept indoors. That meant there was considerably less grazing pressure on trees that stuck up above the snow. Deer numbers were also far lower because of a number of factors: eg more people lived in remote areas, were subsistence farmers etc and part of the reason they survived was because they took wild animals for the pot. The Victorian landowners worked very hard to increase deer numbers with the Earls of Breadalbane for example clearing villages from around Loch Tulla and managing the land so as to increase deer.

The other factor is the cumulative impacts of years of grazing which means that land that once provided a fair amount for herbivores to eat is now relatively impoverished and can support far fewer.