It has been known for some time (see here) that significant numbers of capercaillie, black grouse and red grouse die in collisions with fences each year, with some studies suggesting up to 1/3 of capercaillie die in this way. While the focus in Scotland has generally been on deer fencing, all fencing kills, a fact that seems to have been missed by the Cairngorms National Park Authority Planning Committee when they approved a new “stock” fence around the Coire na Ciste car park to deter people from walking down into the Glenmore Forest (see here). (Committee members asked about the height of the fence but not whether it would be marked). Research has also shown that marking fences (see here) to make them more visible to grouse species reduces mortality by 60%.

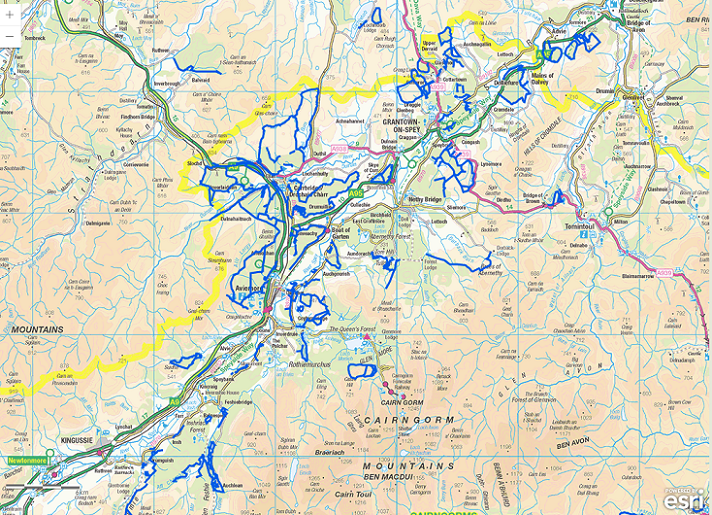

Given the plight of the capercaillie, which is once again heading towards extinction in Scotland, one might have thought the single most important step that could be taken to save them would be to remove fencing in the areas where they remain. The Cairngorms Capercaillie project has produced a very useful map showing fences in capercaillie areas (see here). The amount of fencing on Speyside, the last remaining stronghold for the species, is remarkable:

The position of the Forestry Commission, as it then was, back in 2012 was that “the construction of new fencing to protect woodland and trees in habitats supporting these two grouse species should be minimised, and the fences removes as soon as management objectives have been achieved”.

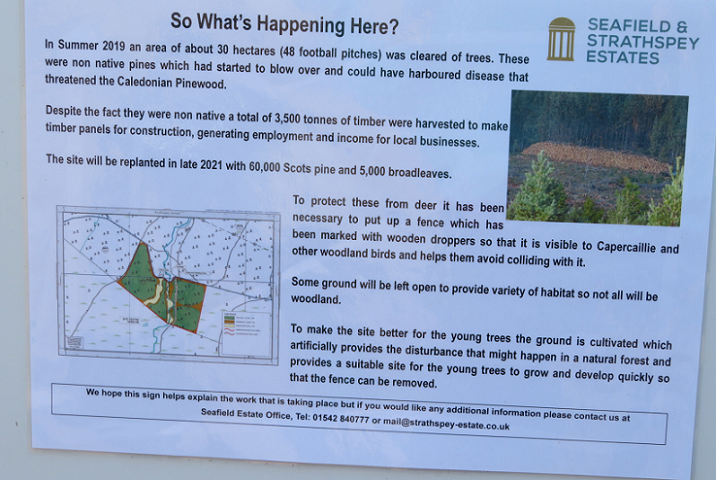

The only reason deer fencing is required is because high deer numbers prevent natural regeneration of woodland. As has been shown on the Glen Feshie estate, if the management objective was to keep deer numbers at c2 per square kilometre, fences could be removed completely and woodland would regenerate naturally. The problem is some landowners want to retain high deer numbers while also keeping the Cairngorms National Park Authority happy by expanding the extent of native woodland. The inevitable consequence is deer fencing.

I first became aware of the extent of the fence-marking at Kinveachy on a walk three and a half years ago. The orange plastic netting is not just a blot on the landscape, it tears in the wind leaving little bits of plastic all over the countryside. The first orange netting used was not resistant to ultra violet light and degraded very quickly. Netting now is UV resistant and guaranteed for eight years, not a long time. Scandalously, the Scottish Government is still providing grants to put up this plastic netting through the rural payments scheme (see here), despite worldwide concern about the amount of plastic entering the natural environment.

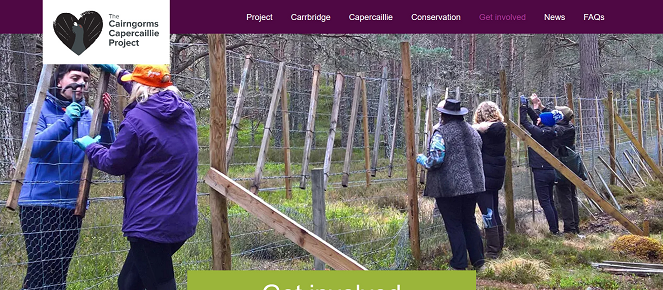

Part of the problem is plastic is the cheapest option, which may be why the Cairngorms Capercaillie Project gets volunteers to put wooden droppers up on deer fences within the area, saving landowners a bob or two in labour.

But if you look closely at the photo you can see the droppers are attached with plastic ties. In fact plastic ties are being used extensively with a variety of different products used to make fencing more visible to capercaillie.

All these small bits of plastic which will inevitably enter the natural environment. Surely we should be doing better in a National Park? One wonders how long it will be till capercaillie and black grouse start dying because they have ingested plastic?

The failure to tackle overgrazing by red deer in the Cairngorms National Park has resulted in a raft of conservation projects that have had damaging consequences for the natural environment. Both the pearl mussel project, which made extensive use of tree tubes (see here), and the marking of fencing to reduce capercaillie deaths, has introduced significant quantities of plastic into the natural environment. This is contrary to the statutory conservation objectives of the Cairngorms National Park. However, as far as I am aware, the Cairngorms National Park Authority has never questioned what is going on or why the Scottish Government continues to fund such damaging practices. It is time that changed and it acted.

Far better than using wooden droppers though, and the most likely way to save the capercaillie, would be to remove ALL deer fencing in the Speyside area. That would reduce deaths by fence strike still further. What is more the Scottish Government, through the Rural Payments Scheme, provides grants for the removal of fencing (see here) and for reducing the height of deer fence to stock fence height (see here).

The problem is there are no grants for estates like Seafield, which are trying to expand tree cover, to shoot deer that come in from neighbouring estates attracted by all the tree-food. With Fergus Ewing, who favoured the large traditional landowners, no long in charge of rural affairs, perhaps there is an opportunity for the CNPA to persuade the new Cabinet Secretary, Mairi Gougeon, to change Scottish Government policy? While they are it, they could also ask her to let them ban use of plastic in the National Park prior to a national ban coming into effect.

Postscript

After writing this, Seafield Estate got in touch and provided this information:

“Our records on fence inspection show that in the last five years there have been no recorded capercaillie deaths from fence strike on marked fences.

The orange netting in the photos you show is nearly 20 years old. It was one of the first areas of marking and dates back to a time when barrier netting was the recommended treatment for fences. At that time Seafield Estate also removed over 20km of fences in the Kinveachy area alone and over 40km on the estate as a whole. This reduced the fences to those considered essential and these were marked.

More recently we have moved to wooden droppers and our staff have worked hard to remove plastic debris from areas where less UV stable netting has deteriorated.

The fence shown in your images is vital and separates the hill deer population from the low ground population and enables us to manage the hill herd, outside the plantations, to 2-5 deer per square kilometre. This successfully allows regeneration of the native woodland in the designated site.

While we are working on reducing the numbers in the plantation areas, the matter there is complex and more difficult to deal with which is why sensitive species, particularly native trees, still require fence protection.”

I’m saddened and disappointed to see this type of fencing being used. For similar reasons, approximately ten years ago, it was used extensively in King County, Washington State. It’s now lying in little brittle bits on the ground, causing even greater ecological damage. I do appreciate the purpose behind it’s use, but surely there is another type of material that could be used to provide fencing? I realize cost is a factor, but at what cost to the environment?

P.S. I was born and brought up in Newtonmore.