It is most welcome that the collective voice of those calling for an end to the use of plastic tree tubes is growing in strength and that Forest and Land Scotland has committed to minimising their use (see here). But our National Parks should go a step further and ban their use completely.

Many people have been uneasy or concerned about the use of tree tubes for years but walked by the plantations of plastic, trying not to think about their impact on nature and the landscape. Prompted in part by David Attenborough drawing attention to the impact that plastic is having on the world’s oceans, plastic tree tubes now feel like an affront, an example of how human created systems abuse the natural environment. Many who were silent, myself included, have now started to speak out and challenge the use of tree tubes.

When you come across a sea of plastic within an area of native woodland, such as that which stretches up along the Ledard Burn, the affront feels even greater. It’s as if the forestry industry is in denial that trees seeded and forests expanded for millions of year before humans ever started to plant trees. Indeed tree tubes are often used even where native woodland is regenerating naturally.

I had walked all round the lower stretches of the Ledard Burn in 2017 to look at the hydro construction (see here) and there was evidence of woodland naturally regenerating everywhere. What the policy makers in Scotland don’t yet appear to have realised is that trees can rapidly recolonise abandoned farmland in upland areas just as is happening in other mountain areas in Europe, like the Alps and Pyrenees.

So addicted is the private forestry system to tree tubes that we even use them on patches of ground where there are already trees regenerating naturally. Every time I see tree tube now I look to see what is growing round about:

I have been Whitelee Windfarm a couple of time recently and, while there is a lot of natural regeneration, the range of species is quite limited. Setting aside the issues of how much carbon is released from soils by planting, there is a case to plant trees to promote greater diversity of tree species and along with that other wildlife. But why is plastic needed in areas where there is evidence that naturally regenerating trees are surviving browsing by animals?

The planting by the Ledard burn raises a similar question:

The photo also illustrates a number of other issues associated with the intensive use of plastic tree tubes:

- They break or get knocked over, either by the wind or by browsing animals, killing the tree.

- They create even aged stands of trees, which in the longer term is likely to be less beneficial for wildlife than trees that regenerate naturally over a period of years (although the way that birch regenerates, by colonising bare ground, also tends to create even age stands).

- Once the tree shoot emerges out of the top, it is the perfect height for deer browsing

As a consequence, although tree tubes are often justified as a means of preventing damage by deer, unless deer numbers are controlled there can still be significant damage. So why are plastic tree tubes used?

There are a number of reasons from a tree planting perspective. Tree tubes prevent seedlings and saplings from being crushed by other vegetation or cut off from the light. They speed up initial growth, giving trees a head start, and prevent browsing by voles or hares. All of these factors, however, could be controlled by other means if only we were managing the wider natural environment better (see here).

The real problem is the grant system for forestry in Scotland, which has and is being driven predominantly by targets for tree planting. The potential for natural regeneration, including as part of continuous cover forestry (see here for explanation) as practised in other countries, has generally been sidelined by government. Instead we have a system where funding for woodland expansion and development is focussed on the number of trees planted. Within that context to qualify for funding private landowners have to demonstrate that a proportion of the trees they are paid to plant survive, or they risk having to repay the grant.

The amount of grant available, however, is far too limited to pay for ongoing management of woodland, as happens say in the Alps. Except in very specific circumstance there is insufficient money, for example, to meet the costs of bringing a small herd of cattle onto a patch of bracken covered ground, as shown in the photo, to break it up or for ongoing control of roe deer numbers. That means landowners and land-managers only option, unless they are very rich and charitable, is to protect the trees they have planted. Historically this was first done through fencing – its far cheaper to put up a fence than employ someone on the land and maintain local rural communities – but more and more in recent years through plastic tree tubes.

While neither plastic tree tubes nor fencing are very effective (fences tend not to keep deer out for very long) both are just effective enough to protect landowners from the risk of having to repay the grants they have received. Small rural landholdings like Ledard Farm, simply can’t afford the risk of having to repay the grant, and which option they then choose to protect trees is then driven by price. On smaller irregular shaped areas of land, as in the photo, tree tubes are significantly cheaper than fencing.

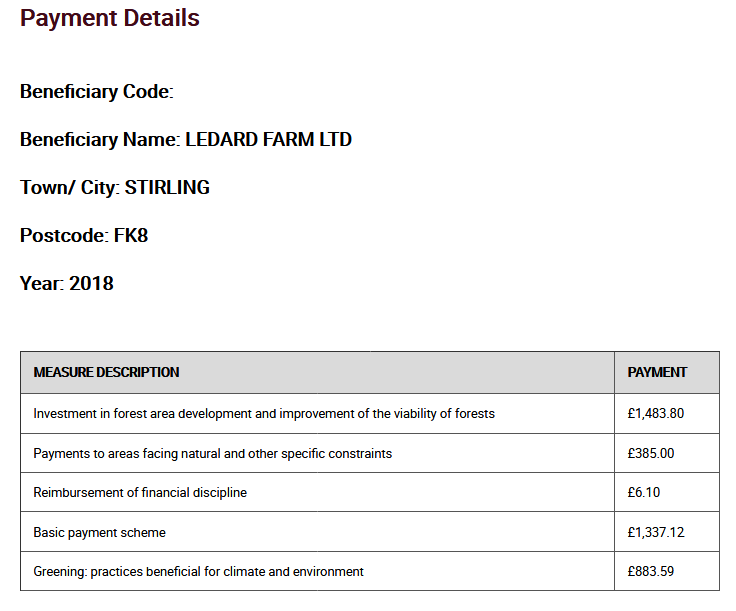

The financial squeeze is illustrated in the case of Ledard Farm, by the amount they received in 2018 for forest management:

While I am no expert on the finances of woodland planting, this is not a lot of money. After consultancy fees, the cost of buying the trees and tubes and transporting them, then paying a contractor to do the planting, the grant in this case hardly appears a money making venture.

Responsibility for this system, which is driving damage to the natural environment, lies not with landowners, though some sporting estates have lobbied hard for grants for forest fencing so they can keep deer numbers high, nor with forestry consultants, though some no doubt have vested commercial interests in forest fencing and tree tubes, but with government.

What needs to happen?

First, we just need to ban plastic tree tubes, starting with our National Parks. Interestingly the Forestry Commission in England, in a publication last year (see here), appears to have gone further in acknowledging the problem than Forestry Scotland, who don’t appear to publish any advice on their website about the need to avoid plastic tree tubes.

Second, our National Park Authorities should be taking the lead on promoting alternative means of woodland expansion, which don’t require either tree tubes or fences, and working out the costs of doing this in different scenarios. For example, control of deer numbers is crucial but the challenges and costs faced by Wild Land Ltd on their large landholdings round Glen Feshie are completely different to a small landholding like Ledard Farm.

Third, the Scottish Government then needs to redesign its forestry grant systems so that landowners and foresters who do want to do the right thing are supported to do so without causing further damage to the natural environment. While I have been critical of Ledard Farm on a range of issues in the past, I doubt very much they started out wanting to cover the land by the path up Ben Venue with plastic tree tubes. Rather I believe they wanted to do the right thing but ended up being forced by the system to do so in a way that cancels out most, if not all, of those good intentions.

Earlier this week I was skiing through Glenmore Forest Park on the south side of Loch Morlich. This is one of the best areas in Scotland for natural forest regeneration both within the forest and extending up the hill slopes into the northern corries of the Cairngorms. Beside the track I came across a large stack of plastic tubes and wooden stakes which looked like they had just been delivered for some forthcoming planting project. What on earth is Forest and Land Scotland playing at? There can be no justification for planting in this part of the national park, in an area where natural regeneration is prolific, and no justification for creating more plastic pollution. If this is what the “Cairngorms Connect” project is all about it needs to be abandoned asap!

Hi Nick

Great article. Firstly I must admit to having a Forestry Degree from the University of Aberdeen! However, I fully accept your points about plastic tubes when natural regeneration is happening. I recently wrote to a private forestry company on this matter because they contacted our local Community Council for advice: I am the Secretary. Below is the actual response when I asked why they used Tuley Tubes in a woodland that is completely Deer Fenced and has masses of natural regeneration. The trees they planted were not all oaks as stated, many being Alder.

“Yes, the east wood is deer fenced but keeping deer out completely is almost impossible and now that there is so much cover, any deer getting in are very difficult to remove. The replacement trees are virtually all oak which are very prone to deer browsing and they are in tubes to ensure that they establish properly. They also have a lot of catching up to do since they are now competing with much more stablished trees. I should also point out that naturally regenerated trees are not nearly as attractive to deer as those grown in a nursery.”

The last sentence is remarkable! They have so much natural regeneration in this woodland that they have to cut it back to let the plastic tube trees get a head start. I despair.

That’s management for you.

Tree tubes are not to stop Deer from eating the saplings, but rabbits. Also Deer fencing works. A good fence will last a minimum of 20 years without any need to be replaced. They also work to keep the sheep out. Unfortunately they do for Capercaillie. Which is why you need to exterminate the excess Deer population and encourage Rabbit eating species if you intend Fence-free Woodland Regeneration.

Considering the amount of tree planting being undertaken in Scotland, England can hardly talk? the unbalanced relationship with predators in the ecosystem is only getting worse, deer numbers are spiral out of control which seriously needs to be addressed by Government. I think in general the right approaches are made towards tree protection, if we want to protect young trees, our choices are limited, ofter when Stika spruce is planted, we often see no protection/ limited being awarded and the complete opposite for broadleaf trees.

Also at Whitelee, the natural regeneration is limited to areas around the footpaths, beyond those areas natural regeneration is poor/ non-existing, does human activity action reduce animal grazing?

https://www.thescottishfarmer.co.uk/news/20072082.farming-v-forestry-time-go-back-facts-planting/

A very interesting article including some home truths about the effects of covering Scotland with trees.

We all need to wisen up about the realities

The people of rural Scotland need to ‘wisen up’ to the urban-based politicians of the Central Belt who, it seems in their ignorance of real facts, are fully prepared to sacrifice rural Scotland, just so they can be seen to be doing something ‘green’ as they try to make Scotland statistically ‘European average’.

This rubbish climate change mitigation strategy, built around tree planting, will see the destruction of farmland and upland bird habitats that’s already well underway. For example, 5000 breeding curlew pairs are already lost directly to forestry and many more to forest edge effects on surrounding farmland – that’s just from the Galloway and Border hills alone (RSPB).

Sorry don’t know why the text was all out of line in my post above.

We all need to wisen up about the realities

The people of rural Scotland need to ‘wisen up’ to the urban-based politicians of the Central Belt who, it seems in their ignorance of real facts, are fully prepared to sacrifice rural Scotland, just so they can be seen to be doing something ‘green’ as they try to make Scotland statistically ‘European average’.

This rubbish climate change mitigation strategy, built around tree planting, will see the destruction of farmland and upland bird habitats that’s already well underway. For example, 5000 breeding curlew pairs are already lost directly to forestry and many more to forest edge effects on surrounding farmland – that’s just from the Galloway and Border hills alone (RSPB).

This ‘strategy’ that will not only oversee rural depopulation and end of a farming tradition and occupancy of the land that stretches back thousands of years but will assist local extinction of birds such as curlews, plovers, skylarks and black grouse.