The day after turnout for the General Election was 67% for the UK as a whole and 68.1% in Scotland its worth considering more lessons from Australia (see here) where voting is compulsory for all government elections and referenda. There too, the lower house, equivalent to the UK’s House of Commons, while like us having single member constituencies uses a preferential or ranked voting system (see here). This allows electors to rank candidates in order of preference and then eliminates those with the least votes until someone passes 50%. This prevents the situation the UK currently faces where Boris Johnson is claiming a clear victory for Brexit on 43.6% of the vote on 67% turnout or 29.2% of the adult population.

While the preferential voting system might well have still delivered for both the Tories and the SNP, depending on where the losing candidates next preference votes transferred, each individual result would have had far greater legitimacy as no-one could argue the winning candidate had been elected on only X% of the vote.

Perhaps the Scottish Parliament could trial such as system in the next local member elections for our National Parks? At the last such elections in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park one candidate won on 17% of the vote (see here) while in the Cairngorms National Park two candidates were elected on just over 25% of the vote and because of low turnout they won with the support of just 10% of the population of their wards (see here). If this is not a failure in democratic legitimacy, I am not sure what is!

Anyway, to access related matters………………..

Could Scotland’s National Parks learn anything from access rights in Australia?

The law about access in Australia is complicated and varies between states but stems from the European colonisation of Australia when all land was declared crown land.

Much of this crown land was then sold, freehold, and under property law the owners of such land have gained the right to exclude members of the public from it. Freehold land covers everything from house and gardens to vast properties – equivalent to our landed estates – in the outback. Access to these areas of land is therefore generally much worse than in Scotland both legally and de facto and is dependant on getting permission from the owner. (I even heard of “tank traps” being created on roads into these properties to prevent people trying to drive along private roads). An important exception in NSW to this general position is angling where the Fisheries Management Act of 1994 created a right to fish “despite the private ownership of the bed of the river or creek” (see here). That is far better than Scotland where angling is excluded from access rights.

The remaining crown land, however, still covers large parts of Australia – even in New South Wales, the most developed area of Australia, this covers 42% of all land. While there is a general assumption in favour of access to crown land, there are different laws for different types of crown land. Arguably the most important areas for access on crown lands are National Parks and State Forests, which have a statutory duty to promote public enjoyment of the land, though access can be restricted in certain circumstances such as fires (see here).

The largest type of crown land, however, falls under pastoral leases for cattle and sheep grazing which cover 44% of Australia. These leases contain provisions for off-road Public Access Routes by vehicle – which are fairly essential for getting to remote places (and help avoid those tank traps) – and contain a presumption in favour of recreational access provided that the holder of the lease is notified first. That leaseholder can then refuse access in certain specified circumstances (eg animal disease).

Crown Lands can also be held under Native Title (which give aboriginal people certain collective rights over the areas they live). A current court case (see here) is considering where Native Title can override public access to a beach in Western Australia.

Complicated! As an illustration of this the decision not to allow tourists to climb Uluru, which received widespread publicity a couple of months ago, appears to have been taken not under Native Title but by the Management Board of the National Park (see here).

Not much, one might think, that Scotland could learn from here. Our access rights are far more comprehensive, clearer and simpler.

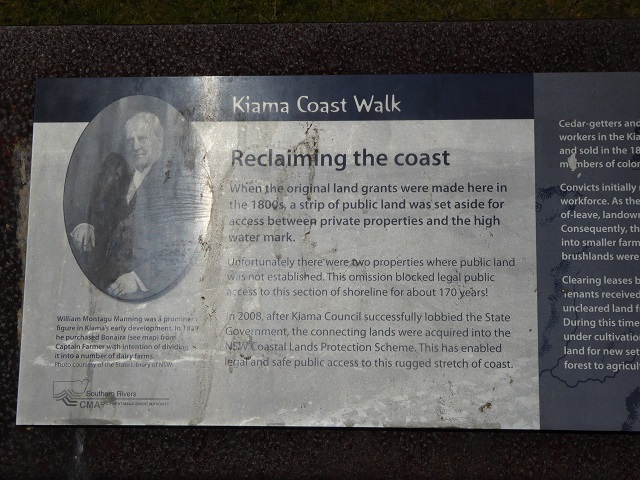

However, a little further on from the sign featured at the top of this post I came across this:

An example of private land being compulsorily acquired by the state to provide public access in a prime location.

Its very hard to find an example of such land acquisition by public authorities in Scotland, even in our National Parks. Consider for example how the Speyside Way has taken years to create because of landowner opposition and where the line of the route has been decided by landowners rather than in the public interest (see here).

This suggests that while general rights of access may be far weaker in Australia, there may nevertheless be a much stronger sense of the public realm and the public interest. Indeed the evidence I saw on this and previous trips suggests that Public Authorities – whether National Parks or not – appear to be far more focussed than here on actively help people to enjoy the land.

Access infrastructure

This is evidenced by the provision of infrastructure for visitors, which generally is far superior to what we have in Scotland.

At Strickland Forest Park, which covers a fairly small patch of rainforest remnant, and which I managed to visit before it too was closed because of the fires, there were not just toilets at the main parking area but picnic benches, barbeque facilities etc.

They also knew how to design a discrete paths through the forest – a skill that is rapidly disappearing in Scotland as its cheaper to build paths with machines.

They also knew how to design a discrete paths through the forest – a skill that is rapidly disappearing in Scotland as its cheaper to build paths with machines.

At the end of the coastal walk mentioned above there was a beach, toilets (every beach seems to have access to toilets) and even a shower to wash off the salt (not yet turned off because of the drought!).

At the end of the coastal walk mentioned above there was a beach, toilets (every beach seems to have access to toilets) and even a shower to wash off the salt (not yet turned off because of the drought!).

On earlier visits to Australia, backpacking in the red centre on the wonderful Larapinta Trail, there were water tanks in each of the camping areas which were spaced a day apart.

Such recreational provision seems to be taken as granted. When I asked people I met in Australia about this they seemed surprised, its something that they take as granted.

Trying to understand this, I came away feeling there is a much much stronger sense of public interest and public service in Australia than here. Much land is held in public ownership, rather than being sold off or leased, which is what government (at all levels) does in Scotland (think Scottish Enterprise’s attempt to sell the Riverside Site to Flamingo Land, Forest and Land Scotland’s leasing of land to private for profit operators like Forest Holidays or Highland and Island Enterprise’s disastrous outsourcing of Cairn Gorm to Natural Retreats). The provision of free recreational facilities – the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority by contrast is trying to charge for everything from use of public piers, toilets and car parks – is part of a much wider attitude that service matters. Sitting on the publicly owned train back to Sydney from Orange, one could not only order a meal for £5, staff would bring it to you in your seat!

Whether this sense of the worth of the public will survive Scott Morrison’s right wing neo-liberal government, which asserts private is best, remains to be seen. It reminded me, however, of what we have lost and why our National Parks should be making the case for the public realm instead, as at present, trying to make money out of what should be public goods.