The consultation (see here) on the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park’s draft woodland and trees strategy, which is intended to set the strategic direction for forestry in the National Park for the next 20 years, closes on Monday. At the LLTNPA Board Meeting in March, which agreed the consultation, it was revealed that the Strategy had been drafted with the Forestry Commission, as it then was. In my view that explains most of the weaknesses in the document, which is very worthy and full of good aspirations but provides no mechanisms to address the many issues with forestry as its practised at present in the National Park. These have in large part been created by the former Forestry Commission, whether as the largest landowner in the National Park or as the forest regulator.

The Woodland and Trees Strategy is written primarily as a vision and guidance document for new woodland creation, which supports the Scottish Government’s drive to create more woodland, and future woodland management. It is not based on any analysis of the current position and provides no mechanisms for changing where we are now to where the National Park wants to be. This post takes a look at the main issues which should have been subject to a proper analysis need to be tackled.

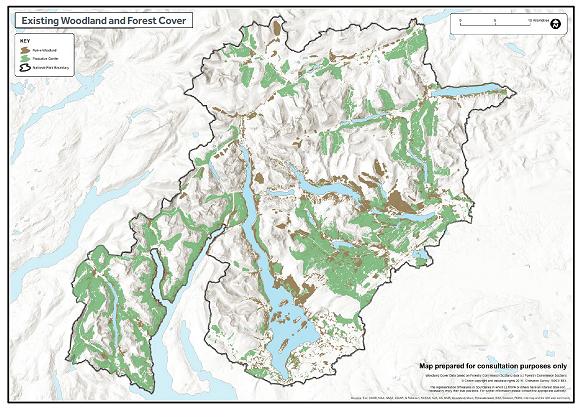

Extent and type of woodland cover

Scotland, as the Strategy points out, has one of the lowest levels of tree cover in Europe, c17% compared to the European average of 38%. The Scottish Government has set a target of 21% by 2032 but this was before it declared a climate emergency. Within this context the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park has a much higher level of tree cover than most of Scotland at 30% but only a quarter of this is native woodland, the rest is conifer plantations. The Strategy repeats the target set out in the National Park Partnership Plan that there should be 2,000 hectares of woodland expansion by 2023 but that is it as far as analysis and targets go. How much new woodland, and of what type, the LLTNPA and Scottish Forestry want to create for the remaining 16 years of the strategy is not stated. With the climate emergency and need for all public authorities to rethink what they can do, I can understand why it might be hard to set firm longer term targets, but that is surely a reason to review the Strategy in three years, not ten as proposed at present.

The fundamental issue for the National Park, however, is not total woodland cover but how it changes the balance from intensive conifer plantation to native woodland over the next 20 years. In the Cairngoms National Park native woodland cover exceeds conifer plantations, which seems appropriate for a National Park so why not in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs? . There are no targets for native woodland, however, in the draft Strategy, not even for new woodland creation – a gaping hole.

To set realistic targets for native woodland in the National Park as a whole would require analysis of when existing conifer plantations will reach maturity and what factors then need to be considered in the decision of whether or not to convert these to native woodland. Much of this information is set out in current Forestry Plans, now held by Scottish Forestry. Unfortunately, there has been no attempt to provide a strategic analysis of these plans to inform the public how the balance between native woodland and intensive forestry will shift over the next 20 years. That would have enabled an informed public debate about whether this was sufficient or whether Forest Plans need to be reviewed.

There is no analysis either of what work has been done to convert intensive forestry plantations to native woodland to date and what lessons might be learned from this. This would probably show that while some good work has been done in places, like along the east shore of Loch Lomond, its not been without its issues and other areas, such as Cowal, are almost a complete blank when it comes to native woodland restoration.

The UK Forestry Standard and the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park

Right at the beginning the Strategy makes clear that it sees the UK Forestry Standard as being appropriate for National Parks. The claim that “the importance of National Parks is recognised within the Strategy” is highly misleading. There are just 11 references l to National Parks in the 232 pages of the UK Forestry Standard. Most of these are contained in caption to photos or references to National Park legislation in both England and Wales and Scotland. There is no separate or higher standards for National Parks. That helps explain why the intensive forestry management practices of the Forestry Commission in the area have not changed one iota since the Loch Lomond National Park was created.

Right at the beginning the Strategy makes clear that it sees the UK Forestry Standard as being appropriate for National Parks. The claim that “the importance of National Parks is recognised within the Strategy” is highly misleading. There are just 11 references l to National Parks in the 232 pages of the UK Forestry Standard. Most of these are contained in caption to photos or references to National Park legislation in both England and Wales and Scotland. There is no separate or higher standards for National Parks. That helps explain why the intensive forestry management practices of the Forestry Commission in the area have not changed one iota since the Loch Lomond National Park was created.

There is NO attempt within the Strategy to analyse whether the work being undertaken at present under the UK Forestry Standard is appropriate for a National Park or not. There is evidence from forest plantations across the National Park (see below) to show that its not.

The draft Woodland Strategy consultation provided a real opportunity, based on the evidence of what’s been going on, for the LLTNPA to advocate the need for higher standards in the National Park and for a new standard for Scotland. Its still not too late for them to do so.

The LLTNPA would not allow a road like this for a hydro scheme so why do they think its acceptable for forestry? This is the route of the Cowal Way, no less.

A shockingly designed and executed culvert with road batters behind too steep to re-vegetate.

Everywhere you look wood, an important resource, is wasted. Leaving it in place helps acidify the ground, preventing native flora from regenerating, and blocks access. A desert for wildlife.

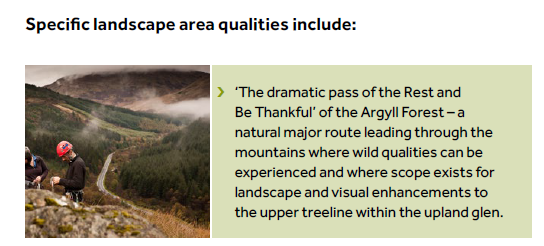

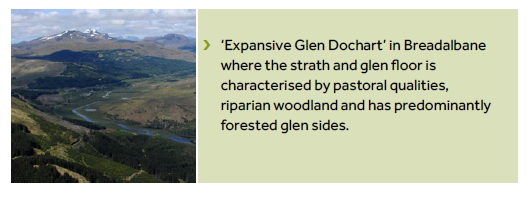

Landscape

The massive conifer planting of the 1980s has left a huge legacy in the National Park. The strategy aspires to re-structuring plantations but says nothing about what resources would be needed to do this or the timescales

The Landscape Capacity Study for Trees and Woodland which forms part of the strategy examines the capacity of different areas within the National Park to accommodate NEW woodland and forestry planting. The consultants were NOT asked to consider the existing landscape impact of forestry. I wonder why? In effect what this means is the Strategy contains NO analysis of the adverse impact of existing forestry schemes. Its shifted the baseline to make what the Forestry Commission has allowed over the last forty years acceptable. Its not.

The Cairngorms National Park Authority has recognised the landscape impact of hill roads, even if they are still struggling about how to address this, so why isn’t the LLTNPA doing the same for the dozens of forestry roads in the National Park?

The consultants who undertook the landscape assessment make it clear they have not made any attempt to assess the landscape impacts of new woodland, whether native woodland or conifer plantations, from the top of the hills:

“the field assessment has taken place from a selection of easily accessible key viewpoints

located on important recreational and transport routes. Consequently, the assessment of

capacity focuses on the approximate view shed from each viewpoint and therefore, does

not cover those parts of Sub-zones that are not widely visible from the viewpoints. In

practice, most viewpoints are located in lower-lying areas and views from mountain

summits and paths have not been considered”

To my mind that invalidates the entire assessment which the LLTNPA has used in the Strategy to say where new woodland would be acceptable and where not:

While the view from the road is often limited, the landscape assessment nevertheless finds positives in some of the worst forestry landscape disasters in the National Park:

Despite much talk about the adverse landscape impacts of blanket forestry and clearfell, industrial forestry practices having carried on regardless, whether in National Parks or not – all according to the UK Forest Standard of course.

One is left wondering whether there is anything that impacts on the landscape in the National Park which the LLTNPA would find unacceptable? (Think Flamingo Land).

Recreation and access

Everyone agrees that woodland is an important resource for outdoor recreation, whether walking, cycling, children playing, bird watching and ultimately for the physical and mental health of people. The Strategy regurgitates the usual recreational objectives without providing any analysis of how far the existing forest resource is meeting those objectives. The answer, as far as the conifer plantations in the National Park are concerned, is not a lot:

- Access, even on popular paths, is regularly stopped because of forest operations without alternatives being provided contrary to the Scottish Outdoor Access Code (see here for example)

- The Forestry Commission has failed to invest itself in path networks in the National Park recently but instead used the Mountains and the People project to get money from the lottery. An abdication of its responsibilities. With the Mountains for People Project coming to an end, its now not clear how the upgraded paths will be maintained let alone if any new work will take place

- Large blocks of conifer forestry or subsequent clearfell are practically impassable and still block access to many hillsides stifling recreational opportunity

- The Forestry Commission has done very little to help deliver new camping provision in the National Park, indeed its converted important sites like that at Ardgarten to luxury chalets

- Many of the camping permit areas provided by the Forestry Commission under the camping byelaws are of abysmal quality and not fit for camping. The provision they have come up with is far less than that which is needed to satisfy demand and they have done little to respond to the popularity of campervans outside of Forest Drive.

- Nothing has been done to promote hutting on the forest estate in the National Park (and there is no mention of this in the Strategy)

- Very little has been done to deliver new mountain bike trails in the National Park – one thing which intensive forestry plantations could be good for

Without any analysis of what needs to be addressed, the Strategy is unlikely to deliver for outdoor recreation

Wildlife

Most of the best wildlife in the National Park, apart from that found underwater, is to be found in native woodland. The contrast between what’s found in maturing conifer plantations and native woodland is striking. But so is the contrast between farmland and conifers. The Strategy provides no analysis of how conifer plantations have led to the extinction of many species from areas of the National Park where they were once found. I have a friend on the Cowal peninsular, which is dominated by conifer forestry, and in his lifetime its become a wildlife desert.

A proper analysis of the role of existing woodland in providing a space for wildlife and the impact of current forestry practices on this might have formed a sound foundation for future management and change. It might for example have reinforced the arguments that more value should be given to maturing native woodland, such as that at Balloch. It could have enabled targets to be set for the return of wildlife to areas where its now absent.

The draft strategy provides no means of delivering for wildlife, something that should be central to what the National Park does.

Jobs and housing

When the Forestry Commission was created, part of its mission was to maintain communities in the countryside and it was responsible for various initiatives such as forest villages. Those days are long gone, forestry has become ever more centralised and a significant proportion of the work contracted out. While the Woodland Strategy gives a nod to the economic importance of forestry, there is no analysis of how far changes in the way forestry is managed has contributed to rural depopulation or of how many people living in the National Park now work in the forestry industry and where. There will obviously be some around Aberfoyle, where Forest and Land Scotland has its new regional office ,while the NGOs, such as the Woodland Trust at Glen Finglas, do employ people who live locally and feel ownership for the forests where they work.

Without a proper analysis of what needs changing there is no possibility of the National Park fulfilling its statutory responsibility to promote sustainable economic development. More specifically, there is a real risk l of further rural depopulation if land is converted from agriculture to forestry on the industrial model.

There are of course alternative ways of doing forestry, such as those promoted by Reforesting Scotland for many years, but there is no analysis of the extent to which these operate in the National Park either.

Consultation and engagement

One of the objectives of the Strategy is improved community empowerment. Its summarises a number of ways in which people can theoretically become involved and have a say in woodland management but again there is absolutely no analysis of how effective this is at present.

How many bits of the forest estate did the former Forestry Commission, for example, hand over to local communities in the National Park and how has this gone? There are some community hydro schemes, such as at Stank Glen and Donich, but how does this land managed for the benefit of local communities compare, say, to the land the Forestry Commission has handed over to Forest Holidays, which operates at Loch Lubnaig and Ardgarten and is now controlled by a hedge fund?

And what about engagement with recreational organisations about the recreational issues identified above?

Resources

Arguably, however, the most important analytical gap in the Strategy concerns resources. How much was the Forestry Commission spending on forestry in the National Park, both directly on the national forest estate and indirectly through grants to private landowners, before it was fully devolved. And of this:

- the breakdown in expenditure on native woodland compared to conifer planations

- how much has been spent on deer fencing to stop the excessive deer numbers in the National Park destroying trees

- how much has been lost through disease and windthrow (the Strategy refers to the impact of Phytothora Ramorum on larch trees but does not say how much it will cost to remove all the larch) and what is the cost of disease control, most of which costs stem from intensive forestry practices

- how much is spent on outdoor recreation and the value of recreational work undertaken on Forestry Commission land paid for by others (e.g the cost of the Loch Chon campsite and expenditure by the Mountains and People Project)

One could go on. Without knowing how resources are currently being spent, its impossible to plan for the changes which the Woodland Strategy rightly aspires to. Forest and Land Scotland and Scottish Forestry need to change the way they allocate resources if any the objectives set out in the Strategy are to have a realistic chance of success. Their silence about their intentions should be viewed with great suspicion.

A vision but not a strategy

Strategy “A plan of action designed to achieve a long-term or overall aim.”

Look up any dictionary and the definition of “strategy” invariably refers to a plan designed to achieve something. The Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Woodland and Trees “Strategy” contains no plans. Its therefore not a strategy in any meaningful sense of the word. It is better described as a vision plus guidance. For it to become a strategy, it would need to set out some sort of high level plan for each of the 8 “strategic” objectives its has set. That in turn would require it to analyse the current position compared to where the LLTNPA would like to be.

A proper Strategy, however, would require the LLTNPA to assert its moral authority and statutory duties over the new bodies which have replaced the Forestry Commission, Scottish Forestry and Forestry and Land Scotland. It would mean the LLTNPA questioning and challenging what has been done by the state forestry industry. Unfortunately the LLTNPA appears far too weak to do this, though who knows perhaps Board Member like Chris Spry who appear to care passionately about conservation will make a stand? The Strategy contains lots of good aspirations and some quite sensible guidance, it just avoids the elephant in the room. Unless that is addressed, I predict few of the aspirations in the Strategy will be realised and Scottish Forestry and Forest and Land Scotland will continue to devote the vast majority of their resources to industrial forestry in the National Park.

Thank you for this analysis.

Efforts to restore Native woodland have been taking place along Loch Sunart for over 20 years. The native Oak woodlands along the sealoch’s north shore were extensively damaged by intensive planting of conifer in the 1960’s and 70’s. With light removed from the hillsides native tree species could not compete. Since the confers were felled as part of a forestry commission sponsored project approx 15 years ago, a stunning transformation has taken place. Initially these newly open spaces became dense thickets of self seeded Rowan and Birch, with further tangles of bramble, bracken and blackthorn. It has taken a concerted effort of repeated woodland management to thin the quicker growing species to permit the dormant and slow growth oak saplings a chance to thrive. Those wishing to learn about what is required to restore ancient woodland might be interested to study the Sunart Oakwoods project.

Tom, I agree the LLTNPA should be learning from what is happening elsewhere, both in Scotland and abroad. Interestingly there is not one single reference in the strategy to research or learning from elsewhere. The Cairngorm National Park has been way ahead, despite in many ways facing more severe challenges (private landowners committed to grouse farming) but there are no references about what they have been trying to do or what could be learned from them. Part of the problem is that the LLTNPA does not have a conservation team worthy of the name – not the fault of individual staff, there are just far too few of them – and I suspect they don’t have the time or power to set out the lessons that might be learned from elsewhere

We need electric quad bikes for us disabled to enjoy the work done by the commission.