In the last couple of weeks Flamingo Land, which the multi-millionaire developer Gordon Gibb has tried unsuccessfully to rebrand as Lomond Banks, has become a national political issue. By that I don’t mean a party political issue – most politicians, both nationally and locally, are still sitting on the fence – but one which is of concern to a large part of Scotland’s population. The revised Planning Application, which was made public three weeks ago, has attracted widespread media coverage and has become a significant “story”. That has increased awareness among the general public dramatically and along with that public concern: how it is that our public authorities are proposing to develop and privatise a key public space in a National Park and at the “gateway” to Loch Lomond? The number of objections lodged through the online portal set up by Ross Greer MSP and the Greens (see here) had reached 52,716 this morning and counting. This makes Flamingo Land the most contested Planning Application in Scottish history.

While the likelihood is that the decision on whether or not Flamingo Land goes ahead will ultimately be decided politically, the detailed planning proposals are nevertheless important. For those concerned about the development, the risk is that the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority tries to dismiss or minimise the importance of the vast majority of objections on planning grounds, claiming they are too general. Its significant therefore that a number of detailed objections on specific issues are now being lodged on the Planning Portal (see here). Following my post on “Flamingo Land and the privatisation of public land at Balloch” (see here), this post takes a more detailed look at how Flamingo Land’s proposals will affect the ability of the public to enjoy the area.

What’s at stake

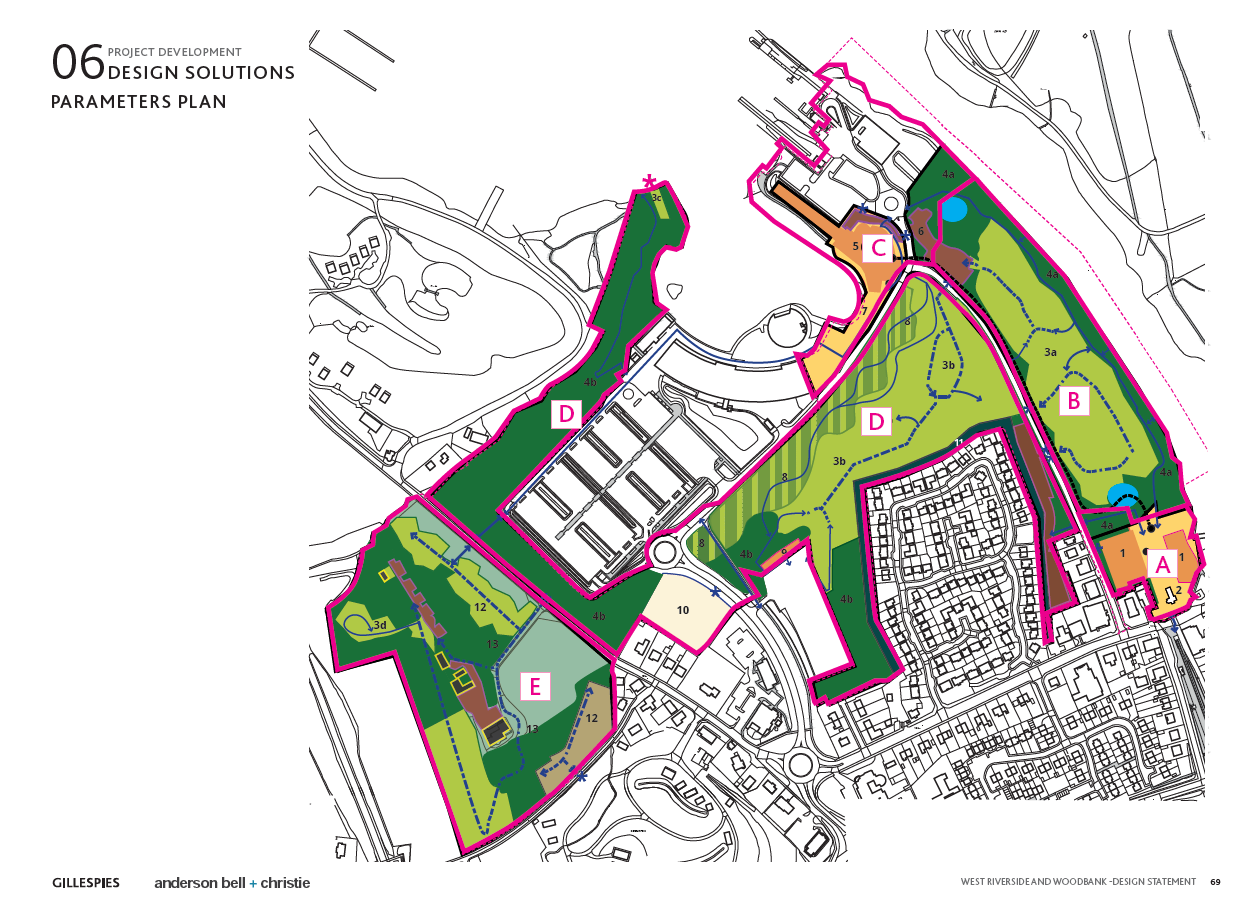

Almost all the land contained within the planning application (boundary above) can currently be enjoyed by the public. Or, as the Design Statement puts it: “The baseline existing site incorporates:

Areas of woodland and greenspace used as publicly accessible open space”. That space includes the Pierhead area, the Riverside, Drumkinnon Woods, the former grounds of Woodbank House and the strip of woodland west of Drumkinnon Bay which is leased by the National Park Authority. This is not to claim that the quality of the experience all this land offers is always high, that it could not be improved or that none of it should be developed – but the starting position is one of open access for all.

From the very start, Flamingo Land and the LLTNPA have claimed that they wish to maintain public access throughout the site. In planning terms this is a crucial issue because one of the LLTNPA’s four statutory duties is “to promote understanding and enjoyment (including enjoyment in the form of recreation) of the special qualities of the area by the public”. If the details of the proposals effectively exclude people from freely enjoying a large proportion of what is the gateway to Loch Lomond, which makes the site even more important in terms of public access, then the LLTNPA should be rejecting the application in principle.

This post argues the evidence from the 9 sections of the “Design and Access Statement” lodged with the revised Planning Application demonstrates conclusively that public access won’t be maintained. In effect the proposals are that a large proportion of what is now public space available for public enjoyment will effectively be converted into space that can only be used or enjoyed privately, for a fee.

The proposed development of green space

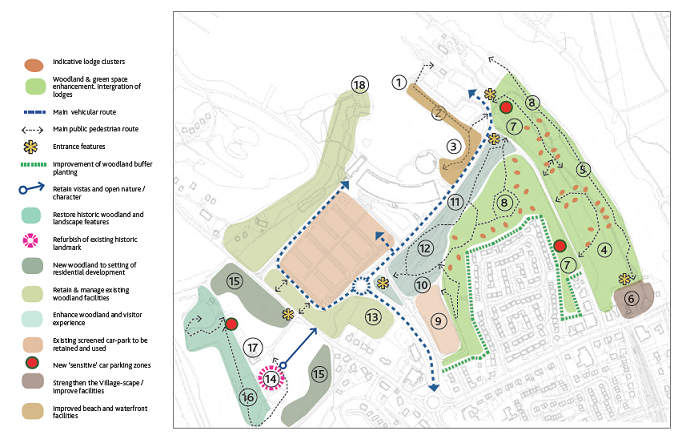

Flamingo Land’s Planning Application appears to deliberately minimise the extent to which public green space will be lost. It contrasts the yellow of the “resort” with the green “woodland” implying large areas of unspoilt countryside will surround the “main development”. The truth is that most of the woodland will not be left green at all but filled with holiday lodges and some housing.

The green areas may have been zoned for “Visitor Experience” by the National Park Authority in the Local Development Plan but the impact of filling these with lodges will not be that much less than the proposals by Cala Housing to cover the Riverside Site in housing which were rejected 30 years ago. You cannot cover an area with lodges without affecting public access and the quality of enjoyment that people derive from this. There is lots of evidence for this in the Access and Design Statement.

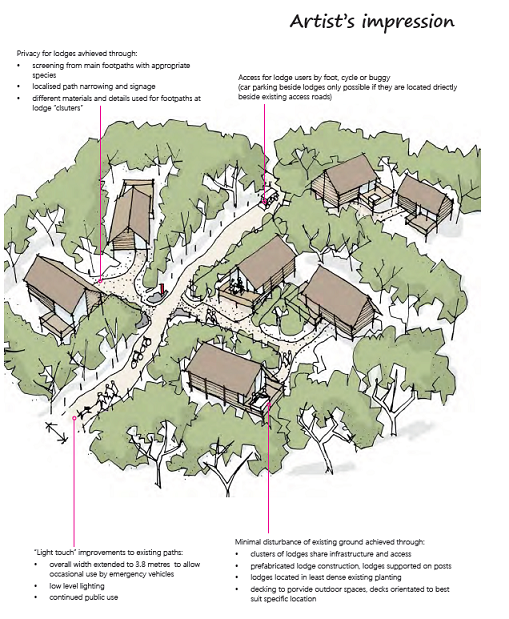

The key word here is privacy! The clusters of lodges and associated infrastructure such as decking effectively remove land from public access. Access around the Lodges may not, initially, beexplicitly banned but it will be controlled and prevented by design: “These lodges will be accessible by foot or golf buggy only along public access ways, utilising discrete, attractive signage to discourage public access into more private areas”. If you decide to wander over to cluster of lodges, there will be no doubt you are invading someone else’s privacy. It will be hard to do so in any case, apart from by path, because of all the new trees planted as “screening”. Defensive gardening is likely to be a more accurate description. Most people will feel deeply uncomfortable in such circumstances and keep away whatever the signs say initially. It will, however, only take one break-in before people are asked to contact site management before entering or “private” signs start appearing. The overall effect is that public access will be limited to a few paths compared to what people have at present.

The converse of the statement on “Access”, that “Paths through woodland will continue to be accessible by the public” , is that the public will be excluded from the rest of the area. Land that we currently own.

Devoting most of the land to lodges for private use and protecting them for private enjoyment, is no good for children who want to play, people whose dogs currently run free or for people who simply enjoy walking off-path. I exaggerate slightly. Some public area will apparently be retained for picnics, “gathering” and public art.

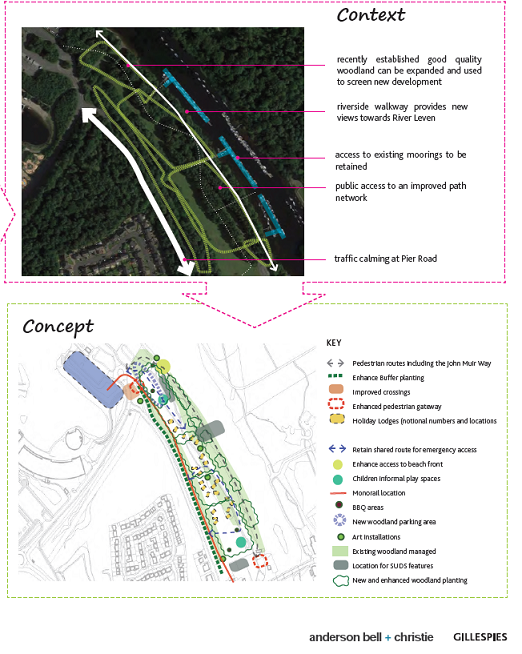

While the map above helps illustrate how lodges will dominate the woodland, their impact will be will be slightly different on the Riverside and Drumkinnon Woods part of the site.

Impact of the Riverside part of the development on public enjoyment

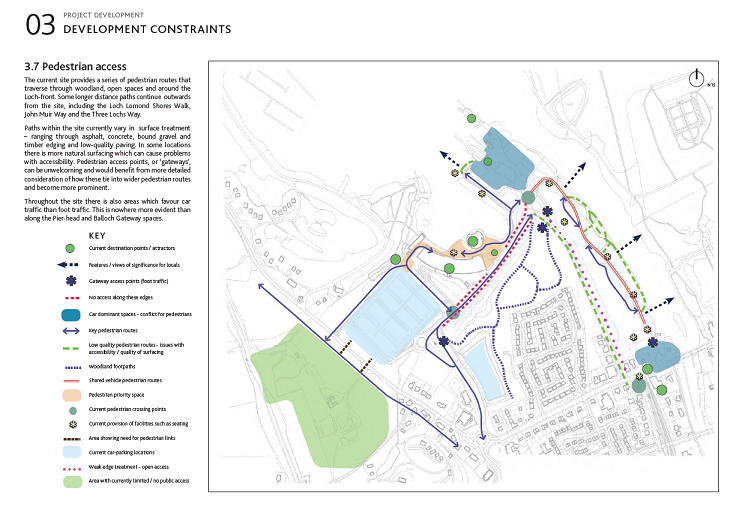

On the Riverside, public access will effectively be channelled down an upgraded path along the shore of the River Leven.

What with the road, new parking, enhanced buffer planting and monorail running along the left hand side of the site no-one is going to want to walk there. Access down the middle will be blocked by clusters of lodges and who would want to walk through what is effectively a posh chalet park in any case. That leaves access along the shoreline.

Along the shore Flamingo Land trumpets that access to the moorings will be retained. While access to the moorings used by the various boat clubs is to be maintained, this could hardly be otherwise, and this is the route taken by the John Muir Way. Whether Flamingo Land intends to renew the leases that the Boat Clubs have with Scottish Enterprise is less clear. Its quite possible in future that they will find some other “better” use for the river, luxury houseboats maybe, which will leave the public sandwiched between two sets of “luxury” developments.

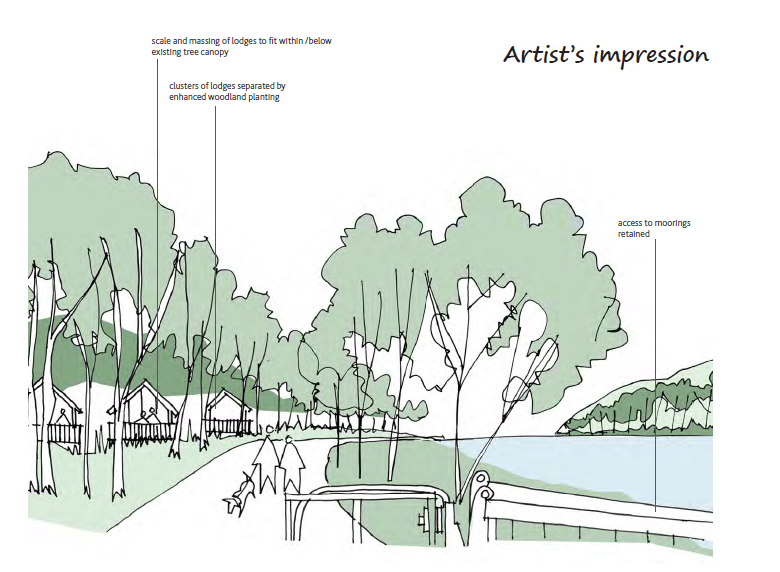

The artists impression shows what access will be left:

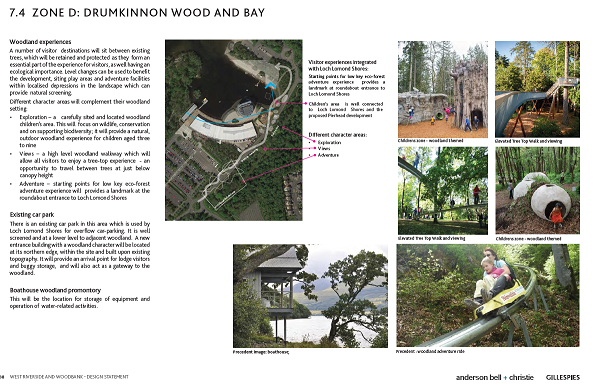

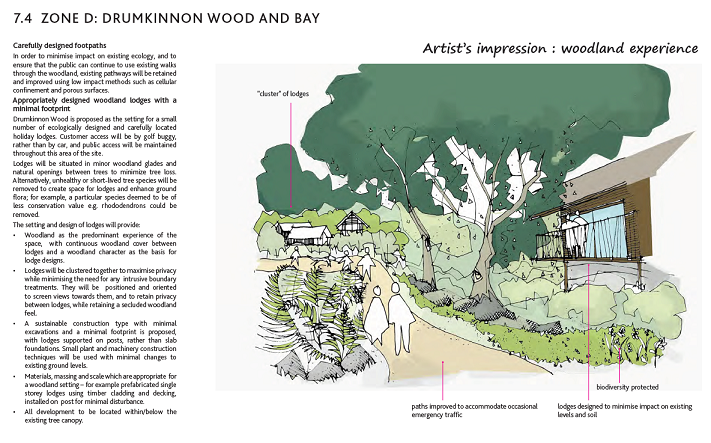

Impact of the Drumkinnon Woods part of the development on public enjoyment

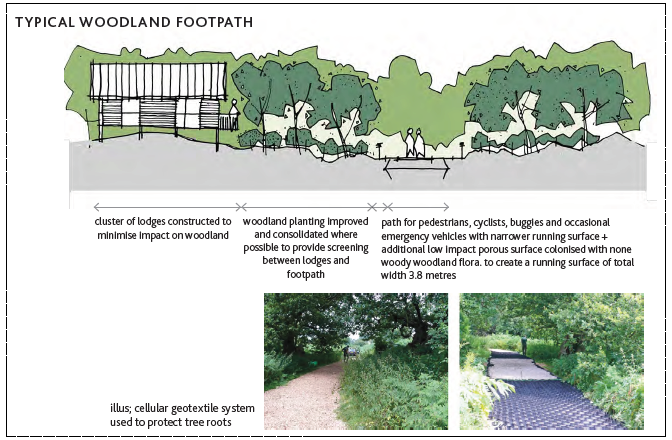

The proposals for Drumkinnon Woods, where the woodland is far more continuous, are rather different. These woods were NOT included in the Local Development Plan as part of the area to be developed for “Visitor Experience” and the LLTNPA should have never, as a consequence, allowed the Planning Application to include it. Flamingo Land is proposing 32 Lodges for these woods which will be located in glades, that is areas of younger trees or open space between the older trees.

What this means is that the main areas of open space on the southern eastern half of the site between the trees are all to be developed, effectively excluding the public.

The dotted lines between the lodge clusters are described as “enhanced pedestrian access” – for lodge users may be, but not for the public. Besides the issues of walking past lodge doors, the general public will have to negotiate their way through an “entrance hub”. Elsewhere this entrance hub is described as providing “Security, management & ticketing (5m max height above adjacent car

park)”.

Along the north west side of the site is an area devoted to “woodland visitor experiences” and a “kids zone“. There is no indication about whether these, or the tree top walkway to the Pierhead Visitor Hub, will be open to public for free. It looks more “resort” than enjoyment of the natural woodland environment: “Children’s Play Area. Adventure themed rides and walkways (all installations below tree canopy, max height at entry points up to 12m)”.

How this adds anything to the existing Treezone on the north side of Loch Lomond Shores is unclear (see here). How many Go Apes does Balloch really need?).

That’s not quite how Flamingo Land presents this though:

The main reason for ensuring that the public can continue to use existing walks through the woodland appears to be so they can access the resort of the pierhead.

The overall design concept, public access and enjoyment

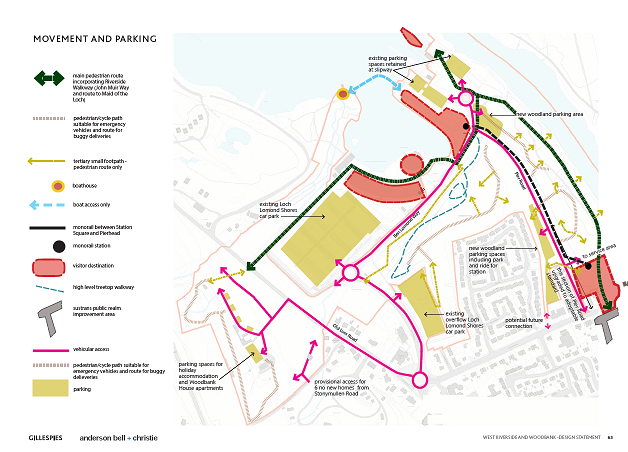

The premise behind both woodland plans appears to be that they should designed to channel people as quickly and effectively as possible to the “complex” at the Pierhead, whether they arrive by cars or at Balloch station: “A new/enhanced Riverside Walkway will form a section of the John Muir Way. It will be designed to encourage visitors to move towards Loch Lomond Shores and the new Pierhead and will be well lit and supervised…………..”

The pierhead development will of course remove land by the lochside, which is the most important of all in terms of people’s ability to enjoy the loch and the landscape, from the public realm and turn this into a paying facility.

There are also a significant numbers of new parking areas – which again effectively remove space which could be used with public enjoyment.

The overall design has little to do with enabling the public to enjoy the special qualities of the National Park and everything to do with making money for Flamingo Land’s owner.

If you want to understand the attitude of the developer, this map provides a great clue. The green area on the left describes Woodbank House and grounds and is described as “unused”, which is not quite true, and “no public access” which is definitely false. Flamingo Land appears never to have heard of access rights, let alone appreciate why they are important.

What needs to happen

The LLTNPA’s senior management – or it is their Chief Executive? – clearly support this planning application or they would have never let it get so far. While the LLTNPA Board has a record of rubber stamping proposals from senior management in the past (the Cononish goldmine for example) its possible, if there is enough public outcry and they are given sufficient “planning” reasons to reject the application, that they might do so.

I hope therefore this post might provide some ideas for objections based on the impact Flamingo Land will have on the ability of the public to enjoy what is currently public land. I have appended below the LLTNPA’s policy on open space, a policy which their senior management so far appear to have ignored.

I hope to cover other reasons for objecting in the next few weeks along with further analysis of the rotten Planning Process which had led to the Application. Should the LLTNPA give the go ahead to this Planning Application, there is every reason now for the Scottish Government to call it in for further “independent” scrutiny and its time that people started to call for this to happen. That will add to the political pressure which will ultimately determine what happens.

Appendix – LLTNPA open space policy as set out in Local Development Plan

Open Space Policy 2:

Protecting other Important open space

Development on formal and informal open space (both inside and outside of towns and villages) in public or private ownership will generally not be supported unless it can be demonstrated that:

(a) The open space is not of community value and has no other multifunctional purposes such as cultural, historical, biodiversity or local amenity value; and

(b) An alternative high quality formal open space provision within a convenient distance and

accessible location is provided; and

(c) The proposal complements the principal use of the site and will result in improved

maintenance or enhancement of open space; and

(d) The proposal complements the nature conservation management of the site.

The key principle is to enable tourism development that won’t compromise the key landscape experience.

Very clear and helpful explanation of effects on public access to proposed development.

I believe this land is being stolen from the public. It is a place of natural beauty and should remain so

LLTNPA are failing to uphold their own policies on maintaining public spaces and public access. Further development of privately owned/used facilities that reduce free, general public access is not what is need by people visiting the Loch Lomond area who visit to experience the natural beauty of the area.