While the central Pyrenees has many beautiful natural mountain lakes, there has been significant hydro development for over 100 years and many lakes have been created or extended by dams. We came across hydro schemes on many days of our two week walk, even in remote places.

While the central Pyrenees has many beautiful natural mountain lakes, there has been significant hydro development for over 100 years and many lakes have been created or extended by dams. We came across hydro schemes on many days of our two week walk, even in remote places.

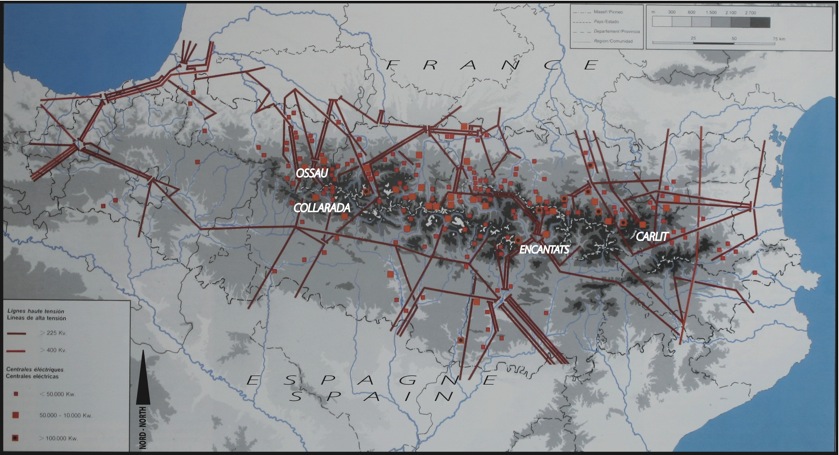

In an interesting article (see here – its in English!) – the history of hydro development in the Pyrenees has many parallels with Scotland – Jean Francois Rodriguez argues that hydro schemes, rather than deterring people from visiting what is often portrayed as a pristine mountain wilderness, have actually helped promote mountain tourism. They have done this, he argues, by helping to make remote areas more accessible but also by forming visitor attractions in their own right.

Applying this argument to Scotland, one could end up concluding that the dozens of run of river hydro schemes which have been constructed over the last ten years should provide the basis for a further boom in tourism! That they won’t is shown by some important differences in the landscape impact of the schemes we saw within and around the Pyrenean National Parks compared to those in Scotland’s two National Parks. This post takes a look at some of the evidence on the ground.

We saw several examples of poor hydro developments in the Pyrenees, particularly near public roads. The more remote schemes however have usually been constructed WITHOUT the creation of any vehicular access tracks and as a result their impact on the landscape and recreational experience is signficantly different to the schemes we have in Scotland.

While the drawdown scars on the Embalse de Brazato were little different, and just as ugly, as those you can see on any Scottish hydro reservoir, what was different was what you could see below the dam:

Access to or from these reservoirs is by footpath, often very rough, and the experience therefore is very different to walking along a bulldozed hill track. As a result, unless you have looked at the map carefully and spotted that a lake en route has been dammed, the reservoir itself can come as a surprise. To put it another way, the impact of these hydro reservoirs, is localised.

I only spotted the pipeline on the hillside below the Embalse del Brazato after we crossed it lower down. In Scotland, partially led by the example of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority, we are now burying these pipes but at the same time have been creating construction tracks which are then left permanently in place. Which is worse, having a pipe above ground or a track?

The answer to the question which is worse, above ground pipelines or tracks, depends partly on how the pipeline is constructed – raised pipelines have a massive landscape impact – and the extent to which pipes and tracks are concealed by vegetation.

Unfortunately in Scotland, we have both, raised pipelines accompanied by tracks in open landscapes and, to add to the injury, pylons too! Walk an hour and a half west from the A82 in Glen Falloch and you are met with the scene in the photo above. The landscape impact is far worse than anything I saw in the Pyrenees – our National Parks should be learning from abroad.

The differing landscape impact of the hydro schemes in the Pyrenees is explained by several factors all of which are under human control and could be adopted in Scotland if there was the political will.

First, while new roads were created to build some of the schemes in the valleys (opening up access and therefore tourism) those in more remote places have generally been constructed using cableways or more recently, for small dams or dam extensions, helicopters.

The unfinished dam above the Respomoso refuge (accessed by a two and a half hour walk up a path, not a track) is a planning disaster which would, if completed, totally change the character of the beautiful upper section of this valley. It appears however to have been constructed without ANY new access infrastructure. If hydro dams in the Pyrenees, even in disastrous cases, can be constructed and maintained without tracks, they could be in Scotland. Its a matter of choice, but, instead of taking decisions which protect the landscape, back in Scotland the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority has led the run of river construction track free for all which which has now spread out to desecrate so much of the Highlands. Its not necessary and our planners and planning authorities need to be held to account.

In fact there are good examples from Scotland of how things could be done as they are in the Pyrenees. Historically cableways were used to construct the Blackwater reservoir dam – at the time the largest in the world – and the Aonach Mor ski development was constructed without tracks but these are the exceptions rather than the rule. They need to be made the rule, particularly in our National Parks and National Scenic Areas.

Second, within the Pyrenean National Parks there has been a deliberate to clean up the remains of construction infrastructure, for example by removing old cableways. Our National Parks should be doing the same in Scotland but including access tracks in this.

Third, because the Pyrenees are far more forested than Scotland and have a scrub zone, the landscape impacts of their hydro schemes are reduced.

Where land was heavily grazed, the impacts of the reservoirs were much greater, as in Scotland:

Our National Parks need to be requiring developers not just to plant a few token trees around power houses, intakes and short sections of track, but be looking at how the landscape impact of the whole can be minimised and, if it can’t, be refusing consent.

Fourth, we saw evidence that more care is taken about the appearance of the hydro dams/intakes in Scotland so they blend in more with the local landscape..

While hydro schemes in the Pyrenees are far from perfect, I hope this post shows that were our National Parks and other Planning Authorities to look elsewhere for examples of best practice, we could have avoided much of the landscape disaster which has been caused by current approaches to hydro schemes by officialdom in Scotland. While it may be too late to reverse the consents to run of river hydro schemes which have been agreed inappropriate locations like Glen Affric, its not too late to insist that the ongoing impact of these schemes should be reduced by removal and narrowing of inappropriate and ugly access tracks learning from what has happened in the Pyrenees. Nor is it too late to stop schemes which are still in the pipeline such as the seven new schemes proposed for Glen Etive (which Parkswatch will cover shortly).

Some very good examples of good practice in hydro schemes in the Pyrenees, Nick, from which our planners should learn.

Unfortunately I believe the problem in Scotland is our planning system and policies which over the years have gradually made it more and more difficult for planners and planning committees to reject poor quality planning applications. The system seems to encourage planning applicants to ‘try it on’. Planning Authorities are often concerned that if the application is rejected or if the applicant believes that the planning conditions are too onerous, the applicant will just appeal all the way to Scottish Ministers. A similar problem occurs over enforcement where there seems to be great reticence to enforce.

The result is poor quality planning applications and weak planning authorities – and if the Scottish Government gets its way on the Review of the Scottish Planning System, mattes will only get worse.