On April 26th 2018 the media (see here for example) reported a fire on the Glen Tanar Estate, Deeside, flames on a front 5km long and at a remote location. Nick Kempe contacted the Cairngorms Campaign, of which I am the Convener, about this and I agreed to visit the site and did so in late May. I do not visit Glen Tanar often as I think it as “too busy” but after a few hundred metres walking I didn’t see anyone until back again in the vicinity of the visitor centre. As I enjoyed my walk I thought “if only Invercauld and Dinnet could be more like this….some hope”.

Glen Tanar is an estate on the east side of the Cairngorms that combines commercial operations such as forestry, holiday lets, tenants and wedding venues with outdoor recreation, with easy access for those that enjoy the environment without walking far and the more mobile. There are marked trails plus access through beautiful woodland to the higher ground. It is home to a National Nature Reserve and the Estate plan includes enhancing and taking care of the natural environment.

The walk in takes you along hill streams, through lovely old pinewoods with blaeberry (bilberry), juniper, and bearberry in abundance. I was even lucky enough to glimpse an immature golden eagle.

Then there is an abrupt arrival at the fire site which is on the edge of the mature woodland adjacent to an enclosed, more recent plantation. The fire looked to me like an out of control muirburn although Nick Kempe had contacted the estate who, to their credit, had responded with this explanation:

“A moorland wildfire started in Glen Tanar on 26th April 2018, as a result of estate activities – a training exercise. It was brought under control in a matter of hours with the help of neighbouring estates and units from the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service.

The total size of the fire was around 73 ha, mostly moorland. Sadly a small area of woodland – around 13 Hectares of regenerating trees, and a few older trees were affected. (Glen Tanar contains around 4,000 Hectares of woodland). The regeneration was occurring on a site that previously been burned to aid regeneration. So hopefully it will not be long before there is a new pulse of regeneration. As you know, heather is fire adapted and Scots Pine is partially fire adapted, so again we are hoping that most of the area will recover.”

Why the estate were carrying out a training exercise in a period of drought the very week the Cairngorms National Park Authority were warning walkers about the dangers of fires (see here) is unclear.

Muirburn is typically carried out to provide a more plentiful food supply for grouse. A number of environmental groups, including the Cairngorms Campaign, have been arguing for its reduction, as it damages the environment, reduces biodiversity and increases soil erosion and water runoff. The haze of muirburn across the North East of Scotland in burning season (from 1st October to 30th April) pollutes the atmosphere with ash particles, greenhouse gas emissions and a pungent odour that has intensified over the years.

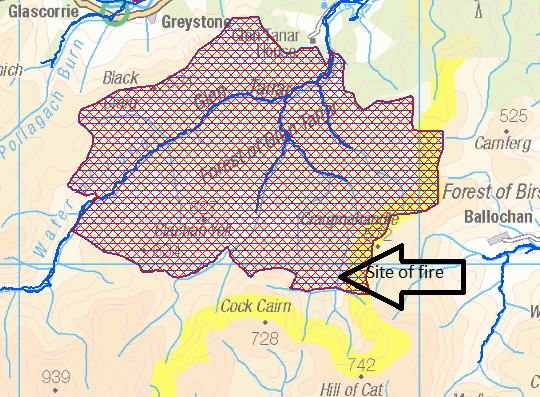

I started off along the Firmounth Road from the car park/visitor area so am heading south as the burnt area begins, the path acting as the east side fire break. First signs of burning are in the old pines at grid reference NO 4807 9042, then on the west side of the path is an enclosed planted area which has been badly burnt. Next is the moorland which is clearly grouse moor because the enclosure has had some markings which are used to reduce the risk of birds striking the fence, there are droppings and evidence of grit and even the burnt remains of what was a nest with eggs, all on the west side of the path.

The south end of the burnt area is at northerly 4855. I walked west from the path up to the ridge at 4712 8972.

From the ridge top all the ground looking east and south from where I started in the woodland is badly burnt with grass growing through the lower slope but only a few deer grass stumps higher so this looks like the hillside where the muirburn started, with I guess a southerly/south easterly wind on the day.

I then walked north along the badly burnt ridge until I reached the end of the burnt area at northerly 9000 and then headed back down the hill towards the planted enclosure and older pines. The land to the west of the ridge I was walking and on the north flank of Little Cockcairn (I’m using OS Landranger 44) was also burnt but did not appear quite so badly. So I would estimate an area of serious burning approximately 30 hectares with as much again scorched moorland and that about 100 old “granny” pines have been badly burnt.

The contrast at this site between mature and natural woodland and scorched grouse moor is stark. I felt very sorry for the people responsible for the burn, despite my antipathy towards the activity. They must have felt sick in the stomach and desperate as their fire started heading for the plantation and took hold of the old pines. I would be very interested to know how they stopped the fire once it was on the pines. Out on the moorland you can see the beat line quite clearly. Again, despite my feelings about some of the activities of neighbouring estates, they obviously deserve a thanks and some respect for their skills and commitment with their assistance in stopping further damage.

It would be worthwhile finding out from the Glen Tanar estate what their “lessons learnt” (other than the obvious one of not burning in the first place). What’s happened rather disproves the argument that is often made that muirburn is a good fire control measure. There is also quite an opportunity here for showing the public what damage can be caused by out of control fires, especially considering the very dry spell we have had.

Every Site of Special Scientific Interest has a Site Management Statement and the one for Glen Tanar includes an interesting section on fire:

“The pine woodland is vulnerable to catastrophic events such as fire, which could be started accidentally within the forest, or could spread from areas of moorland within or adjacent to the forest. Major forest fires occurred in 1920 (550 ha) and 1956 (100 ha). A fire in 1994 was much less extensive, largely because of good fire planning and control. In 2003 a muir burn ran out of control and affected a small area of the adjacent native pine woodland. As the pinewood resource throughout Scotland is so fragmented, recovery from major fires is very slow and they remain a major concern, at both the local and national scale.”

SNH, as the Public Authority responsible, maintains a list of Operations Requiring Consent for each SSSI and the one for Glen Tanar includes “Changes in the pattern or frequency of burning (moorland zone only).” This is far too vague: whatever the debate about the use of fire in extending the pinewood (by opening up the ground to new seedlings,) neither muirburn nor training exercises should be allowed in dry weather or in areas adjacent to old Caledonian Pine Forest Pine when the wind is blowing in the wrong direction otherwise you end up with a disaster like this.

SNH need to fix this and I have made a note to myself to revisit the area over the next few years and see how the recovery progresses.

I went into the Visitor Centre on the way back but no one was around to ask questions of. They have their “forest plan” consultation on the wall inviting comments, which was quite informative. Part of the plans is to have small controlled burn areas on the edge of the wood to encourage forest expansion but, probably because it is a forest plan, there is no information on the estate plans for muirburn.

Overall, despite this event, I feel Glen Tanar is without doubt a lovely place to spend a day and I am going to try to go back more often and explore.

If someone bivying dared to light a fire the estates would be screaming blue murder. Maybe they should listen to themselves before worrying about ‘educating the public’. As for ‘feeling sorry for those responsible’ – why? They did a stupid thing and suffered the consequences (probably not very severe consequences to them)l – at worst they might feel a bit embarrassed, we hope).

Fires will occur naturally and they will be out of control. Would it not be better to accept that burning heather under a controlled environment is better than seeing it go up uncontrolled.

And there in lies the difference between the estates and someone bivying… the estates will largely have it under control, have the numbers to control it and deal with it should it get out of control… while a lone person from the city enjoying the countryside will rarely have a clue on what to do should their fire get out of control and they will not know the lay of the land (a local fire started near where I live set fire to a coal seam that is still burning 10+ years later).

The idea that fire destroys everything other than the heather is a myth. While heather is the predominant plant on the grouse moors, there are several species of grass, several species of moss and lichen, cloud berries, bilberries, and depending on which moor, you can find wild primrose and wild violets.

I am not a fan of grouse shooting, but I think a lot of the arguments against it are disingenuous. Anyone who says that grouse moors are monocultures lacking biodiversity have clearly never been on a grouse moor with their eyes open and/or are pushing a political agenda that ignores reality.

There need only be one good argument against grouse shooting and that is people who shoot on mass living creatures for fun with no intention of eating their kill or controlling pests are sick in the head.

While crimes against raptors and protected species need tougher policing and punishments, it should also be recognised that a lot of endangered species that have been pushed out of their native habitats by urban sprawl, modern farming, and industry are being protected as a result of upland moor management.

Finally, you get a lot more water run off from plantation forests than you do from heather moors and peat bog. Simply visit the north pennines after rain, and then visit kielder forest after rain. You can see it for yourself.

Walk here every year while on holiday. Very few people about, shame on the estate for burning it.