The existing Cairngorms Forest Framework is ten years old and the Cairngorms National Park Authority have been consulting on a Cairngorms Forest Strategy to replace it (see here). The document sets out the “strategic direction on future forest management and the restoration of woodlands in the Cairngorms National Park over the next two decades” with the aspiration to create a forest habitat network as set out in the National Park Partnership Plan. Its divided into sections on Vision, Objectives, Policy, Policy Guidance on Habitat Enhancement, Policy Guidance on Rural Development and Forests and People (or Policy Guidance on Recreation in Woodland) and is accompanied by a 237 page Strategic Environmental Assessment. This post will look at how it proposes to address a number of key issues which should be central to what our National Parks should be about.

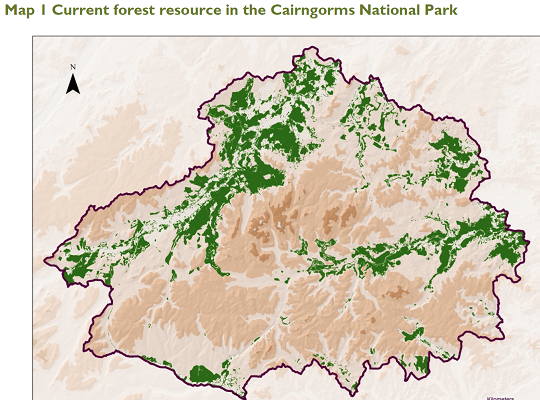

Forest and woodland in the Cairngorms National Park

Much of the woodland in the Cairngorms National Park is pretty unique and has been internationally recognised for this since the 1950s when it was first offered protection. In the words of the Strategy it is:

disproportionately significant for rare flora and fauna. There are 223 species known to be ‘highly significant’ in the National Park, ie between 75 – 100% of their UK population is within the National Park. Of these, 100 are dependent on woodland whilst, by comparison, wetland hosts 12, grassland eight and moorland only one.

Moreover, with 69% of woodland being composed of native trees, compared to the Scottish average of 22.5%, its the only place in Scotland “where native woodland forms the majority of the woodland resource.” And of this 67% “consists of native pinewoods, which are a mixture of ancient forest and woods of plantation origin.” At the same time, the proportion of non-native conifer plantations of species such as Sitka is very low, the lowest Scotland.

Or, to put it another way, the Cairngorms is famous for its Caledonian Forest. A great start for a National Park one might think but the total area of woodland covers just 16.4% of the National Park, less than the Scottish average of 18% and far less than the average in the EU which is 35%. The Strategy does not explain that this is mainly a consequence of sporting estates, with high deer numbers and grouse moor management being responsible on the one hand for much of the treeless landscape in the National Park and on the other for the relative lack of non-native conifer plantations.

The challenge for the CNPA in the Strategy is how to expand the areas of native woodland, most importantly the Caledonian Pine Forest, in order to protect and enhance it (although there is also pressure on them to contribute to the Scottish Government’s target of 25% forest cover by 2050).

A National Park forest strategy is a good thing – and there are some good things in it

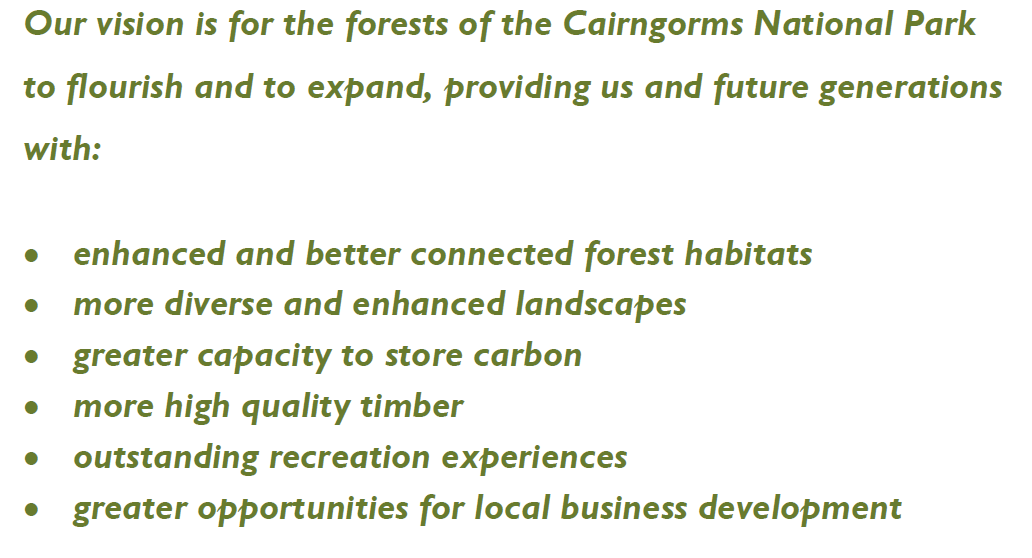

Unlike the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority, who appear content to leave vast swathes of that National Park to industrial scale forestry under the aegis of Forestry Commission Scotland, the CNPA has a vision which does put the expansion of native woodland in the Cairngorms at its centre (as it should do). Its also bold enough to assert that the FCS should be guided by its strategy.

The UK Forestry Standard (UKFS) is the reference standard for sustainable forest management in the UK and defines the standards and requirements for forestry regulation and grant aid administered by FCS. In the Cairngorms National Park there is a public expectation that forest management will be of a particularly high standard with a strong emphasis on environmental enhancement. ………..This Strategy provides guidance to assist FCS and others on the best approach to take before reaching agreement on woodland creations schemes, felling plans and long term forest plans.

That’s miles ahead of our other National Park.

The Strategy also articulates further the strong arguments for managing woodland differently and the benefits this could bring, including:

- the potential for forests to support rural employment

- developing forest products along the lines of Reforesting Scotland’s ideas, from wood fuel to food

- the importance of diverse woodlands as a means of preventing the diseases associated with industrial forestry

- how low impact felling techniques would benefit the landscape

How to realise these ideas?

The Strategy is much weaker on how to realise these ideas. The section on local community involvement is vague, exhorting landowners to consult with local communities but without a mention of the potential of community land ownership to turn the vision into reality, despite the precedent of the community woodland at Laggan.

The reason for this appears to be that once again the CNPA is afraid to challenge the power of landowners. The two weakest sections of the Strategy concern the relationship between woodland restoration and sporting estate management.

On the very high deer numbers of red deer that have thwarted attempts to restore native woodland for something like 50 years, this is what the CNPA has to say:

Deer densities vary considerably across the National Park and in some areas remain too high to enable the recovery of fragile woodlands

And instead of a meaningful plan:

Collaboration between neighbouring deer managers to achieve deer densities compatible with woodland regeneration is encouraged

That is not a strategy for achieving change, its wishful thinking. And moving onto grouse moor management, the thinking becomes even more wishful:

Moorland, managed for grouse shooting, covers approximately 40% of the Cairngorms National Park (c200,000 ha). It is a significant element of the National Park landscape that is managed through a combination of techniques, but most significantly by muirburn, cutting and grazing. Deer reductions, mountain hare control [really?] and stock fencing for livestock on grouse moors has resulted in some significant areas of natural regeneration, particularly along roadsides [not many mountain hares there].

If sensitively designed and located, the aspiration to expand native woodland in the National Park, is compatible with open managed moorland and grouse moor management. Increased broadleaved woodland and scrub on moorland edges would provide an increase in habitat diversity and woodland connectivity for a wide variety of species.

How you retain grouse moors, which cover almost three times as much as the National Park as woodland, and at the same time achieve a significant increase in woodland is not explained. As far as I can discern from the Strategy, the proposed solution is to leave this to the market:

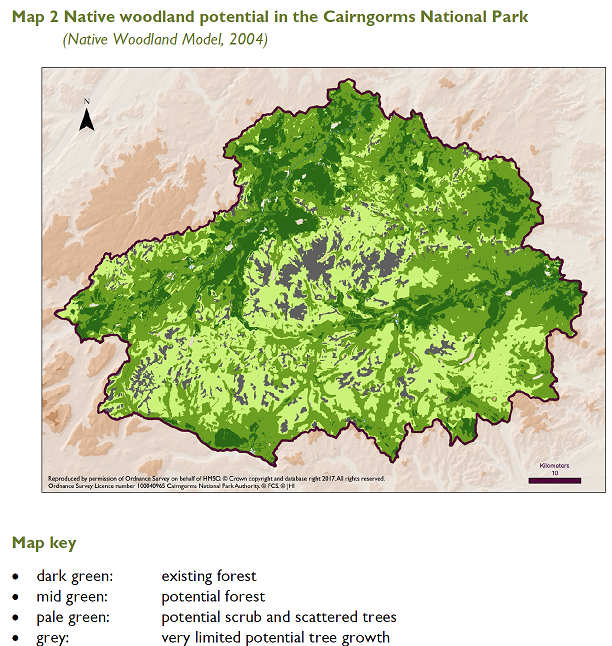

The target for woodland expansion in the National Park is 5,000ha but the CNPA have mapped a much larger area (approximately 100,000ha) “to encourage landowners to apply for enhanced grant funding and to ensure opportunities to achieve woodland expansion, however big or small, are optimised.” In other words this depends entirely on landowners willingness to co-operate. Its not difficult to predict that the same landowners who have supported forest restoration over the last 20 years (e.g Glen Feshie, Kinveachy, Glen Tanar, SNH, RSPB and to a lesser extent NTS) will continue to do so but don’t expect much change in the deserted moorlands of Angus.

The target for woodland expansion in the National Park is 5,000ha but the CNPA have mapped a much larger area (approximately 100,000ha) “to encourage landowners to apply for enhanced grant funding and to ensure opportunities to achieve woodland expansion, however big or small, are optimised.” In other words this depends entirely on landowners willingness to co-operate. Its not difficult to predict that the same landowners who have supported forest restoration over the last 20 years (e.g Glen Feshie, Kinveachy, Glen Tanar, SNH, RSPB and to a lesser extent NTS) will continue to do so but don’t expect much change in the deserted moorlands of Angus.

Native woodland restoration, wild land and natural regeneration

The vision in the Forest Strategy contains nothing about natural processes, rewilding or the relationship between forest restoration and wild land (around 2,100 km2 (46%) of the Cairngorms National Park has been identified as wild land). Nowhere does the Strategy describe how much of the annual target for woodland expansion of 1000 hectares should be by natural regeneration and how much by planting and it provides no clear indication of where natural regeneration and planting is appropriate.

“Woodland regeneration is preferable to new planting in some areas. It avoids disturbance of vulnerable soils and can provide a more varied forest structure which has wildlife and landscape benefits. Already there are some impressive large scale and valuable small-scale examples of native woodland regeneration in the National Park which have been achieved chiefly through improved grazing management”

“Preferable” is a very weak word. Is there nowhere in the National Park where the CNPA is going to leave it to nature to decide whether woodland regenerates or not? The problem is there are some people and organisations who are impatient, who don’t want to wait to see what nature might do and want to plant native trees, normally paid for by the public, everywhere. We end up with gardening, the idea that people can improve nature, as the RSPB has done in Strath Nethy, an idea that is fundamentally in conflict with the whole concept of wild land and threatens to destroy natural soil structures (soils are only “vulnerable” if people start digging holes).

Indeed, it appears that the CNPA does not really believe in allowing natural processes to follow their course even in the finest areas of the Caledonian Forest:

All forests and woods require some form of management. This may be to improve the habitat for rare and vulnerable forest dependent species such as capercaillie and pine hoverfly, to enhance landscape or to improve timber quality.

Nowhere is to be left wild. That in my view is totally wrong. There should be core areas of the Cairngorms where natural processes are allowed to follow their own course. Instead the Strategy says this:

Supplementing natural regeneration where necessary by planting a variety of native species is encouraged.

And;

Landscape and wild land impacts need to be considered at all stages of new woodland creation. There are potentially negative visual impacts from woodland creation operations such as fencing, tubes and forest tracks. They can have short term, but significant, adverse effects in the most sensitive areas and should be kept to a minimum.

Woodland creation is something people do, very different to what nature does, and the CNPA is right to draw attention to all the associated impacts. Do we really want tracks and fences and tubing in areas of wild land? And to claim that the impact of tracks is “short term” is nonsense. In my view, if we do all these things the land is no longer wild.

I am not arguing that there should be no tree planting in the Cairngorms and, having taken a good look at the massive Woodland Grant Scheme between Glens Feshie and Tromie, believe that is acceptable.

But in core parts of the Cairngorms, such as Glen Feshie, Strath Nethy, the upper section of Glen Avon etc, there should in my view be no planting. Unfortunately the Strategy appears to be promoting tree planting in these very places:

Woodland planting and regeneration that supports the enhancement of landscape scale habitat networks is strongly encouraged, especially where this improves connections between river catchments.

The watersheds between the river catchments, such as the Geldie/Feshie or Nethy/Avon are of course some of the prime areas of wild land in the National Park and important as through routes. The CNPA, in a wish to try and speed up natural processes, and create a forest network, appears to want to join these up by planting. This would be an absolute disaster. Its also terrible ecology.

In December 2014 I walked with Dave Morris up Strath Nethy. After several kilometres of treeless bog, the path passed a rocky slope – covered in pine saplings. The lesson, natural regeneration will work in the remotest places but only on ground suitable for trees. We should leave bog as it is and so should the CNPA which also has another strategy – to restore peatland in the National Park!

As dangerous, I believe, are the proposals to restore montane woodland, something which is close to my heart:

This includes the tiny fragments of montane willows that are clinging to remote and inaccessible crags, native trees and woodland remnants hidden within plantations or in remote, isolated gullies within open landscapes that unless protected will die and not be replaced.

The trouble is the Strategy does not say HOW these areas will be protected but instead states:

The restoration of montane woodland, including re-establishing the missing ‘birch zone’, dwarf birch and montane willows, is a priority.

As new and restored montane woodlands are likely to be in highly sensitive, remote locations, careful attention should be given to design to achieve the best possible ecological and landscape benefits.

As worded, this would allow planting of montane scrub species all round the central Cairngorm plateau, gardening on a massive scale. And how will this be achieved? In all likelihood yet more fencing and tracks. The Strategy puts the cart before the horse. In order to establish montane woodland what is needed is a massive reduction in deer numbers, particularly on estates such as Mar Lodge and Blair Atholl where high deer numbers continue to spill over and impact on areas of land where deer numbers have been reduced (such as Abernethy and Feshie. If, once montane scrub starts to regenerate in those areas, certain species are missing, then is the time to discuss whether certain “re-introductions” of selected species is justifiable. However, planting should not be the primary means by which a natural treeline in the Cairngorms is re-established.

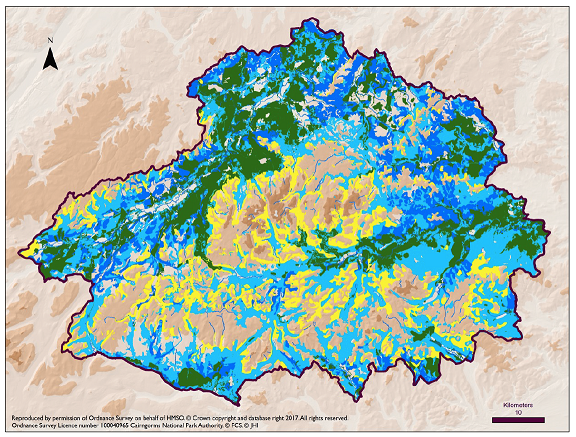

Legend

Dark blue -Preferred Areas Suitability for planting would need to be confirmed at a site level and may require surveys

Light blue – Potential areas Areas within which native woodland creation would achieve multiple benefits through restoration, enhancement and expansion of the existing woodland resources, but where there are known sensitivities eg Natura designation, peatland habitat, and arable and improved grassland

Yellow – Potential montane woodlands Suitability for planting would need to be confirmed at a site level and may require surveys

The incoherence of the Strategy is nicely illustrated by the diagram above. Note how the preferred areas for new forest, dark blue, and the existing areas of woodland (green) do not link with the potential montane scrub areas (yellow) but are separated by what are described as sensitive areas (light blue). Instead of a natural tree line achieved through the forest regenerating upwards (as is happening at Cairngorm for example) we are going to have bits of planted pine forest separated from bits of planted montane scrub. What is missing from the Forest Strategy is a coherent proposal for woodland restoration from the floors of the glens to the arctic alpine zone.

Other issues

There is only one mention of forestry tracks, which will inevitably be needed as they have been on Glen Feshie for new planting schemes, and no explanation of how these fit with the policy position of the CNPA that there should be NO new tracks in upland areas.

The contribution of treeless landscapes to flooding is understated – again no mention in the vision – and in the statements on the importance of riparian woodland there is just one reference to the beaver:

There are currently Eurasian beaver established close to the National Park. It is possible that beaver may return to the National Park in the future. A significant increase in riparian woodland is needed to ensure sufficient habitat to minimise potential impacts of future beaver populations.

Once again the CNPA refers to access rights as only existing if they are exercised responsibly – a misinterpretation of the legislation which gives people a right to access and then, in separate clauses, sets out responsibilities of both visitors and land managers. Why does the CNPA never mention the responsibilities of land-managers, a major issue given that “forest operations” are often used as a reason to restrict access unnecessarily.

The Strategy fails to explain where “the opportunities over the long-term to improve the structural diversity of existing forests and to create new commercial forests that provide a wider range of benefits” exist.

What needs to happen

The Cairngorms Forest Strategy is less a strategy than a policy statement which fails to address a number of fundamental policy issues which are at heart about putting a natural wood, rather than tree planting, first.

To make it a Strategy worthy of the name, the CNPA needs:

- to start with the role that natural regeneration and natural processes should play in extending the area of forest in the Cairngorms and then clearly indicate which areas should be designated for rewilding

- pay far more regard to the importance of wild land and accept that, even with reduced deer numbers, some areas of wild land may never support extensive tree cover

- and then, having established this, identify in what areas planting might be acceptable and how this should be achieved (e.g when and where new forest tracks and fencing might be acceptable)

Thanks, Nick for your critique on the CNP Forest Strategy. I have not had time to ‘plough through’ the documents, but your comments come as no surprise to me. Many of the CNPA documents like this that I have read are inclined to have a similar vague wish list and lack the means to achieve their goals. I’m reminded of the Cairngorms Nature Action Plan 2013-2018 which I recall was full of pretty pictures, vague visions of the future and the only actions were measurement and promotion of ‘ideals’. It will be interesting to see how little of the plan has been achieved if CNPA produce a report of the success/failure of this so-called Action Plan – once we cut through the inevitable ‘gloss’.

As you imply with numerous examples, CNPA seem to have little idea of what strategy and action plans are about. I recognise that CNPA doesn’t have the financial resources to tackle a fraction of what it would like to achieve, however, hoping that the deer and grouse estate owners will listen to these weak words and policies is futile.

Lastly, I agree with your various comments on rewilding. Far too little attention is given by our Cairngorms National Park to enabling the regeneration of our lost landscape and protecting the few wild areas we have left.