“Wild land areas must get the same absolute protection as national scenic areas and national parks. Time is running out for Scotland’s most precious natural asset: its landscape, as more and more wild land is eroded by development”

“Wild land areas must get the same absolute protection as national scenic areas and national parks. Time is running out for Scotland’s most precious natural asset: its landscape, as more and more wild land is eroded by development”

That was the response of David Gibson, Chief Executive of Mountaineering Scotland, after the Court of Session rejected the judicial review brought by Wildland Ltd against Scottish Ministers for giving the go-ahead to the Creag Riabhach windfarm in Sutherland last August. While I agree with the sentiment, unfortunately the purpose of our National Parks has been steadily undermined since they were created and, while having the potential to offer absolute protection to our prime areas of landscape and wild land, have failed to do so. What’s worse, organisations with an interest in protecting our landscape appear to have practically given up trying to influence the Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority, which is one reason why there has been so much less concern expressed about the new Cononish gold mine planning application compared to the Creag Riabhach.

The assumption is that the outcome of the Cononish gold mine planning is a foregone conclusion and, from the Committee Report recommending the application go ahead, it is clear that the Park senior management team are acting as if that was the case. How otherwise could the report conclude that:

“During the construction, operational and decommissioning phases of the mine, years 1-17, this development will be contrary to the Local Development Plan as it will not safeguard, protect or enhance the Landscape, Visual Amenity, Wild Land, Special Qualities, Recreation and Access”

and still recommend the development goes ahead? SEVENTEEN YEARS is an extremely long time for an area to be adversely affected by operations incompatible with the National Park’s objectives.

Not everyone though accepts this is a foregone deal – Mountaineering Scotland to their credit submitted a powerful objection – and the LLTNPA have a legal duty to consider the issues properly at the special meeting to consider the Cononish Gold mine which takes place next Tuesday (see here). This post considers the Committee Report’s flawed assessment of the wild land issues relating to the Cononish goldmine application which has implications for the protection of wild land throughout Scotland.

The application of Scottish Government policy on wild land to the development

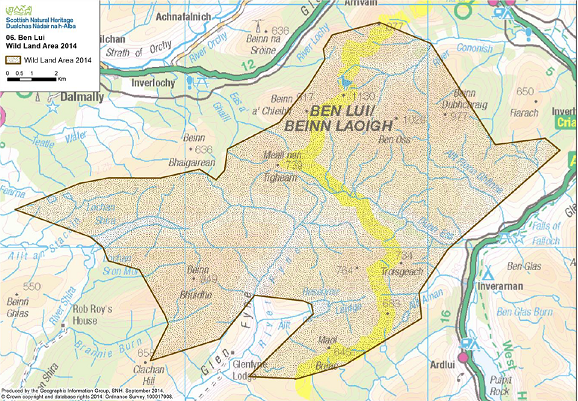

The original application for a gold mine was approved BEFORE the Scottish Government incorporated guidance on wild land into Scottish Planning Policy in 2014 or the creation of the Ben Lui Wild Land Area, which includes the site of the mine, in that year. Government Policy requires that any development proposal on wild land must :

“demonstrate that any significant effects on the qualities of these areas can be substantially overcome by siting, design or other mitigation”.

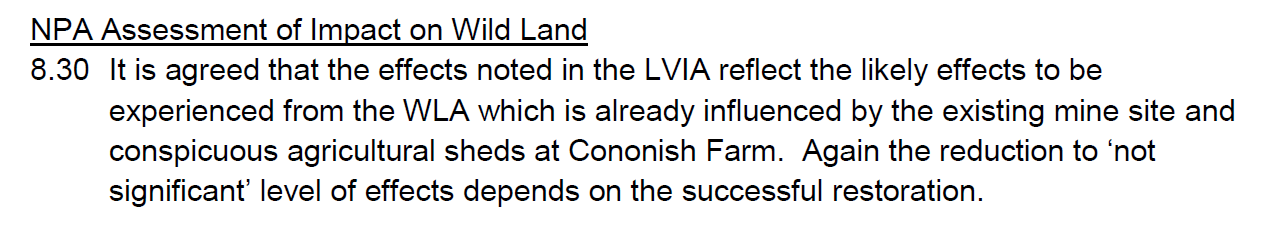

While the Committee Report does refer to this guidance, it then claims:

“There have been no significant relevant changes in planning policy either nationally or locally.”

That a National Park fails to treat the change in wild land policy as being is relevant is unbelievable. Had senior staff, however, accepted that policy had changed they could not have claimed that:

“The principle and acceptability of a mine at this location and of this scale has been established” .

In planning terms, what the Committee Report should have told the Board is that given the original consent had expired and, given the new Scotttish Government Guidance on Wild Land, the whole application needed to be considered afresh or “de novo”.

There are two other fundamental flaws in the Report’s assessment of the proposed development in terms of wild land. The first is their treatment of existing developments

At Cononish LLTNPA are trying to use both a development OUTWITH the wild land area (Cononish Farm) and the existing mine development WITHIN it to justify the development going ahead. Nowhere does Government guidance state that existing developments, whether within or outwith wild land areas, can be used to justify further development in wild land. On this argument, the existing mine at Cononish could be expanded until it covered the entire Ben Lui Wild Land Area and any wild land area from which a windfarm or pylon was visible could be developed further on the grounds that the “experience” was already influenced by development.

At Cononish LLTNPA are trying to use both a development OUTWITH the wild land area (Cononish Farm) and the existing mine development WITHIN it to justify the development going ahead. Nowhere does Government guidance state that existing developments, whether within or outwith wild land areas, can be used to justify further development in wild land. On this argument, the existing mine at Cononish could be expanded until it covered the entire Ben Lui Wild Land Area and any wild land area from which a windfarm or pylon was visible could be developed further on the grounds that the “experience” was already influenced by development.

What makes the assessment even more ridiculous is that in the Greater Cononish Glen Management Plan, which is being offered as compensation for the development, the proposal is to repaint the lurid green Conoinsh Farm sheds to reduce their visual impact. Any National Park worth its salt would have been trying to reduce “visual detractors” throughout the National Park – such as through undergrounding powerlines – but in the LLTNPA what happens is that blots on the landscapes are used to justify creating more blots on the landscape…….

The second flaw is staff’s failure to consider the impact of the designation of the Ben Lui Wild Land Area on their existing policy:

The Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Wildness Study (2011) mapped those areas considered to be most relatively wild and then identified three broad categories ‘core’, ‘buffer’ and ‘periphery’. The development lies within a transitional area on the edge of core but impacted upon by the existing mine building and track reducing the majority of the mine site itself to ‘buffer’. The surrounding upland areas are considered to be some of the most wild areas in the entire National Park.

That policy may have had core, buffer and peripheral areas but the creation of Wild Land Areas has superceded that and the mine is NOW in the CORE WILD LAND area. To suggest that because its at the edge it somehow counts less is therefore totally wrong. Interestingly, the Report says nothing about whether the LLTNPA objected to SNH about how the boundary to the Ben Lui Wild Land Area was drawn but, whatever the case, their duty now is to uphold that policy and not try to undermine it.

The impact of the mine waste on landscape and wild land

“Natural character, remoteness and the absence of overt human influence are the main attributes of wild land.” SNH

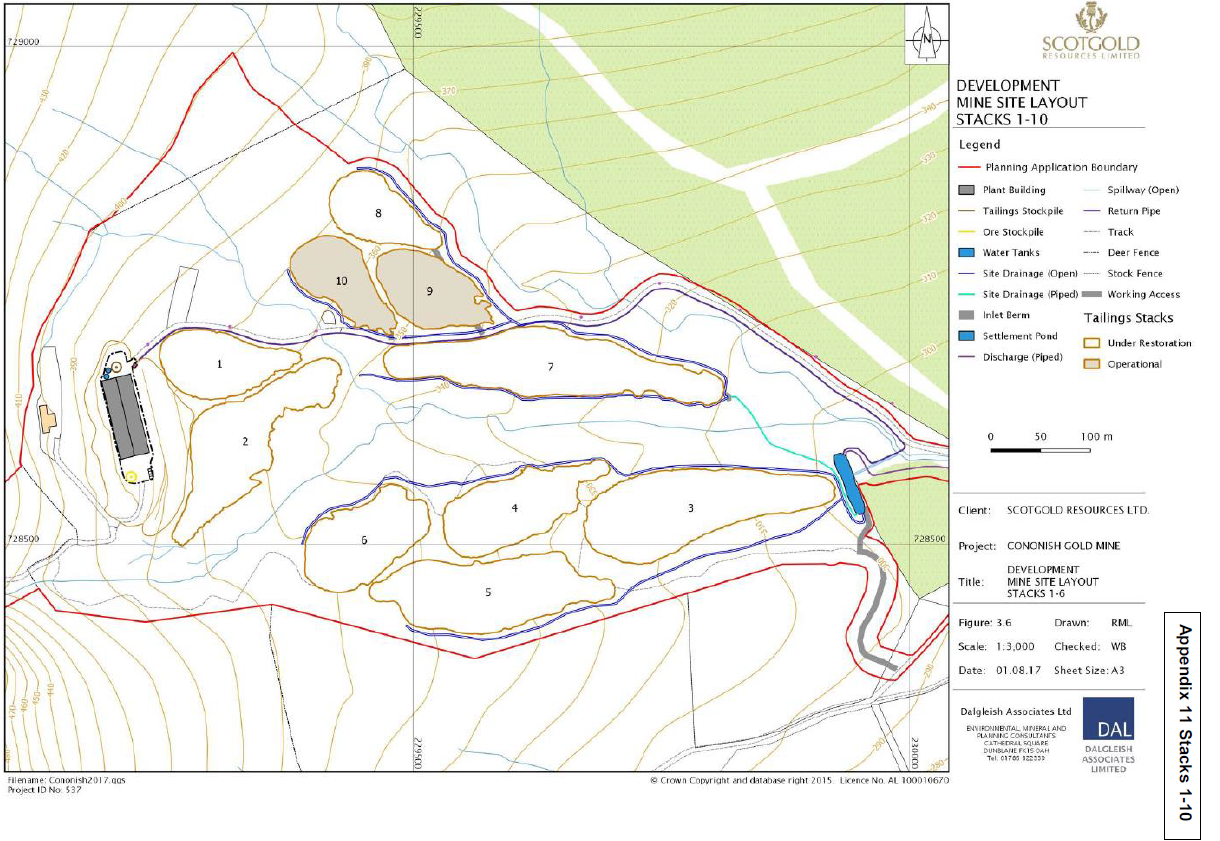

The LLTNPA appears to have accepted Scotgold’s terminology of “tailings storage facility” for the waste to be deposited outside the mine. Its not storage in any normal sense of that word, because its proposed to leave the waste there permanently, or rather until natural processes erode the ten tailing stacks away.

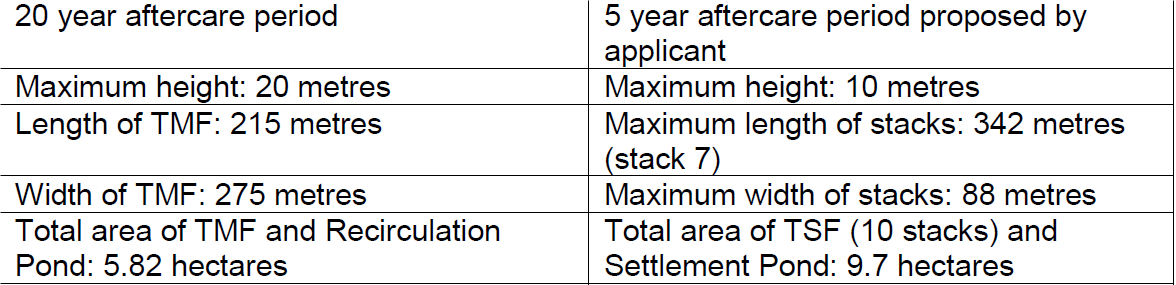

The proposal is to create a new landform, which it is claimed will look like moraine, in an area of wild land. A common characteristic of wild land areas is that, while vegetation has often been highly modified by human interventions, the landforms in them are basically natural and not modified by humans. The LLTNPA’s assessment is that whether or not there is a permanent impact on wild land depends on whether vegetation can be successfully restored on the 10 tailings stacks. This is fundamentally wrong as it fails to consider the creation of an artificial landform on the wild land qualities of the area. What’s being proposed is that 9.7 hectares of designated wild land which has been created through natural processes should be replaced by what at worst could turn out to be a big dump and at best an enormous landscape garden. Neither is an appropriate land-use for Wild Land or a National Park.

The Committee Reports and papers contain many claims that the tailings stacks will look like moraines, for example:

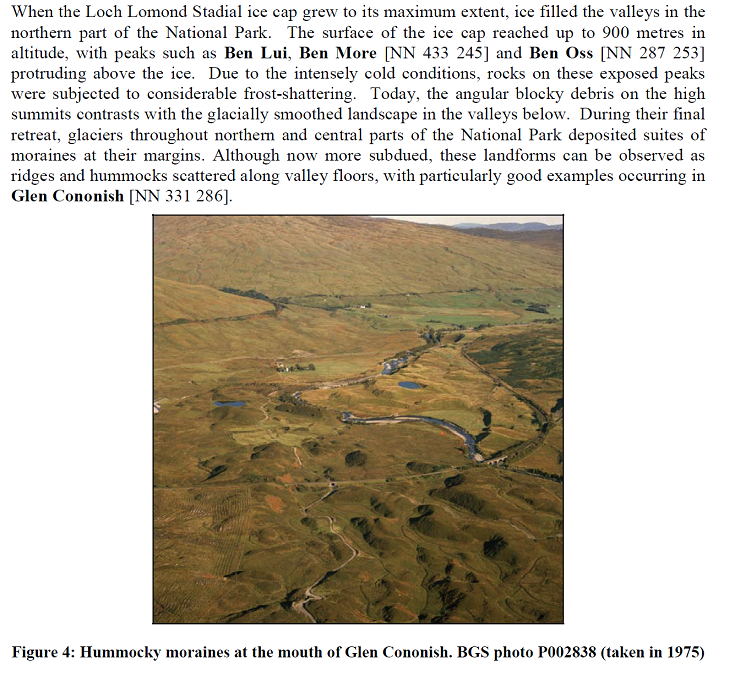

“The primary objective of the tailing stacks is to create a naturalistic landform characteristic of ‘moraines’ similar to hummocky features naturally occurring elsewhere in the glen”.

The Report concludes from that that the tailings stacks can therefore in the long-term can be treated as a restoration of the natural landscape. However, not a single piece of evidence has been produced to substantiate this. I think there is a reason for this: moraine in the form outlined in the diagram above, does not exist in Cononish Glen and could not have been created on this site. Good evidence for this is provided in a report the LLTNPA Commissioned in 2008, which mentioned Cononish Glen several times, and provided photographic evidence of what the existing moraine there looks like:

Key differences between the artificial mounds proposed by Scotgold and naturally created hummocky moraine include:

- the size of the moraine (see below). The proposed Scotgold stacks are far longer and gnerally lower than the hummocky moraine in the glen: if anything they appear more like drumlins, which are elongated heaps of moraine which form under the flow of the ice, than hummocky moraine

- hummocky moraine is full of boulders and when the stacks eventually are eroded by natural processes the difference in composition will become very visible, as will the rate at which the moraine erodes

- the sides of hummochy moraine, including that in Cononish Glen, are often very steep. The tailing stacks cannot mimic this without severely increasing the risk of slope failure

What the LLTNPA should have done is asked geomorphologists whether any moraine of this length, width and height can be found naturally in Scotland and more specifically whether it could have formed here. This should not have been difficult to do as a wonderful article on the impact of glaciers on the landscape published on the UK Climbing Forum last week (see here) illustrates:

The reports show there are signs the LLTNPA’s own landscape advisers have their doubts about the reconstruction:

“From a landscape and visual perspective, the main concern of the proposed restoration relates to the new landform created by the introduction of the tailing stacks and the restoration of vegetation cover as well as the mine buildings. The primary objective of the tailing stacks as set out in the ES is to create a naturalistic landform characteristic of ‘moraines’ similar to those naturally occurring in the local area. This is considered acceptable for the existing landscape context. However, in order to achieve this it is essential that the tailings do not appear as man-made engineered earthworks and are integrated into the existing topography. The satisfactory restoration of the tailing stacks also relies significantly on the majority of vegetation being successfully established from one area to another, maintaining a mosaic of habitats.”

Apart from changing the landform, the LLTNPA’s advisers also state

“as the tailing stacks are designed to shed water, it is unlikely that the restored vegetation will retain wet heath properties, but will be drier. The revegetation of the tailing stacks depends on a range of external factors which should include the implementation of best practice measures including alternative restoration methods should one method fail.”

These concerns however have just been ignored by management. Whatever happened here to the precautionary principle?

Re-interpreting what natural landscapes mean

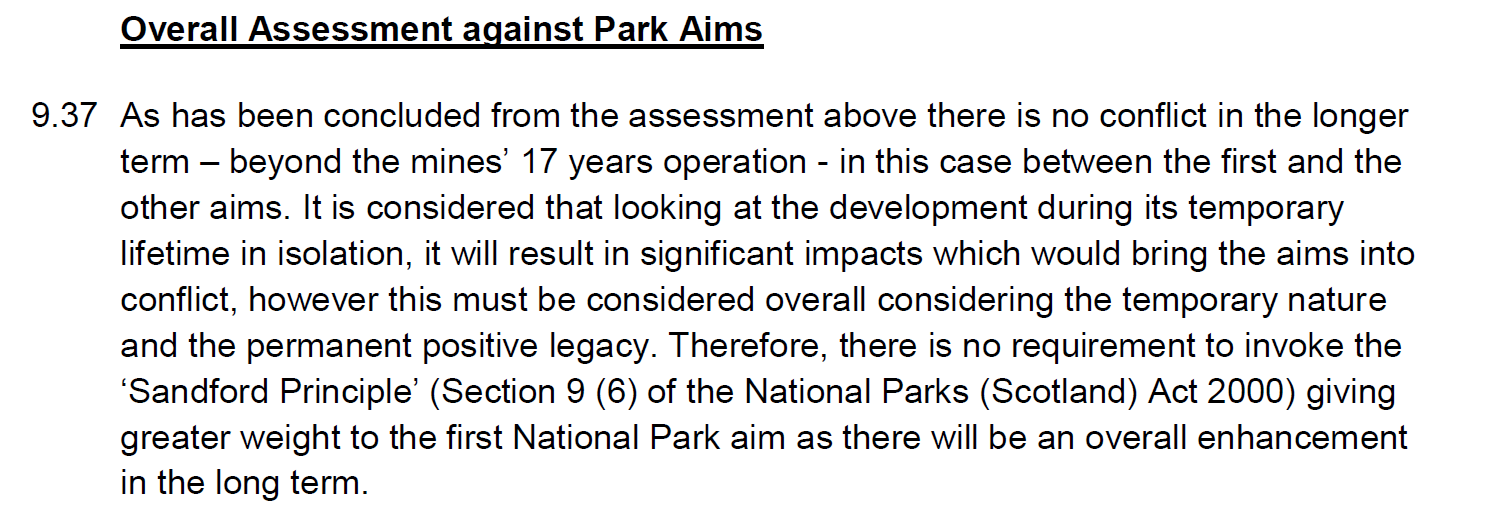

Its worse than this though, the LLTNPA is claiming that this area of Wild Land will be “improved” by the development going ahead – or rather 17 years after this:

This betrays a further fundamental failure to appreciate wild land and natural processes. Nature has a wonderful ability to recover after every armageddon but this takes time. The artificial landscape LLTNPA staff are recommending be created at Cononish is very likely to re-wild again at some point, assuming mining is not extended and even if the ground is poisoned, but not at year 17 and probably not until long after that. The Committee Report provides no assessment of when that will happen.

Instead it contains other proposals which will actually detract from that re-wilding process, most notably planting native woodland in an attempt to hide the mess and erecting fences to protect that woodland from deer. In other words they are planning to alter the ecology as well as the landforms. My view is that in wild land areas we should be leaving nature to follow its own course: the arrogance of humans is to think we can do better.

The implications of the Cononish gold mine application for wild land across Scotland

If the LLTNPA approve this application they will not just be destroying part of the National Park, they will have also sponsored another serious blow to the whole concept of wild land areas. Its not just their flawed reasoning, that any development in or near to an area of wild land justifies another. Its their belief that humans could and should manage everything and that a proposal to create a new landscape, using untested methodologies, will be better than what nature has created.

Whatever happens on Tuesday, people who care about wild land in Scotland need to be strongly arguing that the arguments the LLTNPA has tried to use to justify the Cononish gold mine are flawed and should have no place in any future consideration of Wild Land. Whatever happens on Tuesday, the LLTNPA need to be pushed to develop a new policy that puts the “wild” into wild land.