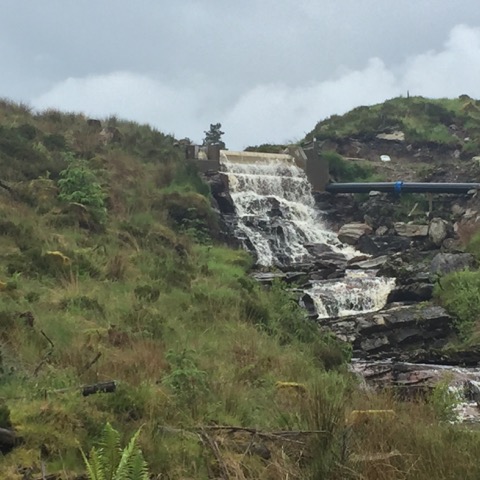

Gross, poorly managed, temporary quarry on Forestry road at head of Glen Finart. NB apparently no regard for H&S or Mines & Quarry Legislation. All photos, save one, by author

By Nick Halls

Following the post on the destruction of a core path and right of way in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park (see here) I thought a bit of wider background, based on experience, of how the area has been managed over the last 50 years might be relevant.

I arrived in Cowal in 1969, and worked as an outdoor education teacher, at Benmore and Ardentinny Outdoor Education Centres. I am now retired but remain a resident of Ardentinny.

During work and leisure, I wandered throughout the area, looking for attractive places and interesting geomorphology. As an aspect of work and personal interest I became fascinated by the detail of the environment; geographical, biological, historical and recreational.

I was quite shocked at the way significant historical features were trashed by industrial forestry practice; fermetouns, sheilings, charcoal burners platforms, water mills, bloomeries, shearing pens, transhumance routes etc. In fact, nearly all the evidence of life in the past. Anything that impeded forestry operations seemed to be sacrificial.

Eviction and emigration has been a continuous process from before 1745 up to the present day. Cowal was not a depopulated wilderness even in the recent the past, it has been created by socio-economic forces which still operate, current expressions of which discourage even visitors.

The area exemplifies the disappearance species due to destruction of habitat – in this case homo sapiens.

I used the locality for teaching map reading and how to navigate in all types of terrain. The area is particularly suitable, as wayfinding in restricted visibility, in forests, at night and in bad weather, depends on interpreting fine contour detail, slope aspect, drainage patterns and detailed route finding. It is particularly important for orienteering which takes place in woodland, because of the restricted visibility.

Access to and through the actual woodland and out onto open hillside, and back through woodland important. The techniques of wayfinding are not only applicable to open hills.

I arrived after the great storms of the late 1960’s, when vast areas of wind blow occurred, to both commercial timber and natural woodland, destroying enclosures and blocking access to beauty spots. Less violent but exceptional storms have recurred frequently since, contributing to the damage, mature woodland being particularly vulnerable. Enclosures, watercourses, paths are consequently very at risk of damage and obstruction.

I experienced at least two full forestry cycles, with replanting of clear fell areas, almost inaccessible due to stumps, waste timber and branches, followed by close planted trees maturing into at first impenetrable saplings then into more mature young trees, and eventually into woodlands reaching ‘economic’ maturity. During the whole cycle the land remains virtually inaccessible, commonly made worse by the spread of non-native species such as Rhododendron, which invade wherever there is sufficient light filtering through the canopy.

I took all this for granted, the changing patch work of forestry operations, as camping sites, pleasant, natural traditional routes, significant historical sites used for environmental studies, areas of mature woodland mapped for orienteering courses were trashed, often with little if any consultation with the local community. None at all with representative organisations of recreational activities.

Catering for recreation seemed not to matter at all, and visitors seemed to be treated as an inconvenient nuisance.

During the cycles water courses were clogged with trees and branches, avoidable local floods did damage to property and public infrastructure and the locality became less and less attractive to visitors. I looked on with dismay.

I slowly came to the conclusion that it should not be happening, and that the Forestry Estate, which is held in trust for the people, but managed by Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS), is being appallingly mismanaged.

Visits to Regional and National Parks throughout Western Europe reinforced the impression that Scotland’s rural environment is poorly managed, but the commercial forestry practice is destroying the ‘amenity’ and potential recreational value of a tremendously valuable ‘public asset’ in a fashion that is largely avoided elsewhere.

Other countries factor in scenic quality, economic return, retaining indigenous industry and employment, catering for recreation, in an environmentally sensitive way, into forestry practice. The imperative across Europe seems to be to retain rural communities and slow down emigration to cities, and as far as possible encourage people to return.

Scotland’s forests seem to be managed in a way inspired solely by financial considerations, by ‘philistines’ who put every other consideration in second place. I believe the current culture of Forestry practice fundamentally betrays the public interest, in numerous ways.

Practically everybody I know who has lived in the area for a similar length of time shares my opinion. Like mine, their children have left, and more and more property used as holiday or second homes, or for retirement.

FCS and local communities

Over recent decades I have tried to engage with ‘here today’ gone tomorrow foresters, all of whom seemed to be decent guys, but who seemed powerless, ‘mouth pieces’ of a distant and unresponsive, autocratic, senior management. The internal culture appeared to be command and control orientated, and quite abusive of more junior personnel.

A practice developed of moving staff around on a migratory posting basis, and employing transitory sub-contractors. There is now no connection between the community and Forestry workers or managers. I was told some decades ago that this change was initiated to prevent Forestry personnel going ‘Bush’ and identifying more closely with the community than the employer.

When the Cowal Office closed, management moved to Aberfoyle, and local connections weakened even further. Clerical support staff lost jobs. Now occasionally, the first point of contact does not even know where Glen Finart is!

When I arrived in the 1960’s, forestry personnel were semi-permanent, and members of the local community, this included forester, ranger/game keeper, fellers and extractors, and a permanent general labour force, employed ditching, maintaining forest roads, brashing, planting etc. Most people occupying the former Ardentinny Forestry village worked in the woods. The community were pretty well informed and I knew personnel as friends. Forestry operations were the background to everyone’s lives. It was done by them not to them!

Now as a consequence of ‘outsourcing’, ‘right to buy’ and retirement/death of former forestry workers, most properties are occupied by incoming residents with no connection to land management. More recent incoming residents accept current Forestry practice as a given, it is just a ‘back drop’. In some cases, they are even tentative about entering the woods, unless there is a way marked path!

When I propose to engage with the forestry about an issue of concern to my neighbours, the uniform response has been that they want nothing to do with the Forestry, because their experience of engagement has been so frustrating and unsatisfactory.

As former professional people themselves, they resent being treated with ‘top down’ patronising, disrespect, by unaccountable public servants. They are particularly irritated by having to deal with very personable young staff, who seem to be no more than ‘messengers’ from a higher command. They tend to prefer to deal with issues themselves hoping that whatever is done will remain ‘out of sight and out of mind’, which is usually the case.

There seems to be a disconnect between what is written, information provided verbally, and what is happening on the ground. From the perspective of somebody who has been resident in the area for decades there seems to be no coherent, long term consistency in practice, or local quality control of operations. Everything seems to be done at the lowest cost and poorest standard

The FCS and NP ‘blurb’ pays lip service to access and conservation, but the reality is an increasingly industrialised, impenetrable wasteland, with depleted bio diversity and loss of wildlife, due to habitat loss.

Within a National Park, and The Argyll Forest Park, created in the 1930’s from land bequeathed to the people of Glasgow as a place for recreation and escape from industry and unhealthy city life, one would like to think facilities for recreation might have a special place. Especially in the context of lack of activity among children and increasing obesity throughout the adult population. Such a facility is as much needed today as it has ever been.

Cowal and the National Park

The Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority appears to take almost no interest in what goes on in Cowal, but treats the Argyll Forest Park as an enormous industrial site, where Forestry Commission Scotland can do what it likes.

The contrast between how FCS is managing forest in the Argyll Forest Park and elsewhere, for example the east shore of Loch Lomond, is striking, though I am not sure their consultation with local communities is better in other places.

The LLTNPA needs to call for FCS to develop an alternative vision for the Argyll Forest Park, one that puts people, whether residents or visitors, the landscape and wildlife before industrial scale forestry. The draft National Park Partnership Plan, currently out for consultation, which fails to refer to the Argyll Forest Park, would be a good place to start.

Excellent article.

I have lived in Ardentinny fot 12 years and in that time nature trails have disappeared not to be replaced.At present Loch Eck viewpoint is becoming overgrown to the point of disappearing.There are many unsightly areas of fallen and felled trees .Tourism is an afterthought.