Over the last couple of years, concerns in the outdoor community about the impact of hydro schemes has increased significantly and on Tuesday I went out with 6 members of the Munro Society http://www.themunrosociety.com/ to share knowledge and views on the ground. The Munro Society’s first objective is “To provide an informed and valued body of opinion on matters affecting the Munros and Scotland’s mountain landscape” and as part of this they have decided to survey the impact of hydro schemes. We went to the recently completed – or should that be compleated? – Ledcharrie hydro in Glen Dochart on what was a pretty wet day.

There was no machinery left of site, which is an indication that the developer, Glen Hydro Development Ltd, believes the work is finished. While I had seen plenty of hydro tracks with oversteep batter sides (banks) – which is contrary to the Loch Lomond and Trossach’s National Park Authority’s Supplementary Guidance on Renewables (see here) – I had not seen mounds of earth, as on the right. The way the land lies here, they are totally out of place and have changed the landscape. These things should matter in a National park.

Afterwards, I checked the planning application.

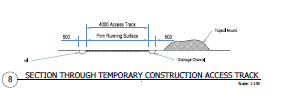

The diagram left shows the mounds of earth on the right of the track were supposed to be temporary. Why then are they still there?

The diagram left shows the mounds of earth on the right of the track were supposed to be temporary. Why then are they still there?

The width of the new track is in places extraordinarily wide, as the double gates illustrate. Double gates have also been left in place at the Glen Falloch Hydro Scheme. One way the LLTNPA could help ensure tracks are narrower is by requiring all double gates to be replaced by single gates after construction has finished.

The LLTNPA’s Supplementary Planning Guidance actually recommends tracks are not even one gate wide:

At Ledcharrie the planning documentation confirms this approach:

“Permanent access tracks will be restored to their original condition upon completion of the works. Temporary access tracks will be removed and the surrounding ground reinstated upon completion”.

and

A permanent track from the powerhouse to the primary intake (surfaced with local crushed stone and about 2 metres in width).

Now I think this is extremely welcome. Two metres is quite wide enough for a landrover or quad bike and would force vehicles to follow the same line along a track, allowing vegetation to establish in the middle of the track. Talking with members of the Munro Society they agreed. Maybe we need a compulsory National Standard for hill tracks in Scotland. The problem at Ledcharrie however is that almost everywhere the planning documentation for the track, and the LLTNPA’s own standards, have been ignored.

The tape measure here is extended to its maximum, 3m. The width of the track is close to 6m and there has been no attempt to restore the banks on either side creating a 9m broad scar up the hill. This should be totally unacceptable anywhere, let alone in a National Park, which says it believes uphill sections of track should just be 2.5m wide.

The tape measure here is extended to its maximum, 3m. The width of the track is close to 6m and there has been no attempt to restore the banks on either side creating a 9m broad scar up the hill. This should be totally unacceptable anywhere, let alone in a National Park, which says it believes uphill sections of track should just be 2.5m wide.

Not all the track restoration is as bad and there is short section above the double gate (above) where it almost meets the 2m specification and there has been a reasonable attempt to restore the land to its original condition. Why here but not elsewhere is a question worth asking? It seems totally arbitrary.

Even here, though, all is not as it should be. On the left bank the developer appears to have run out of peat to place on top of the bouldery soil. The Planning documentation required a:

management plan for the whole site shall be submitted and approved by the Planning Authority. This shall include details of:

- The storage and management of the different habitat types and turves of different sizes and depths; and

- Coding of habitats to ensure habitat turves are reinstated in the correct areas

Unfortunately the LLTNPA does not generally add documents required in a planning consent to the planning portal so its impossible for the public to see plan for retention of turves was agreed. The photos show however that whatever happened, insufficient care was taken in removing and restoring turves, with the result that large areas of ground have been left bare.

The planning consent also included a specific requirement that:

Turves should be reinstated over the pipeline as soon as possible to ensure maximum restoration.

The photo (above) shows this never happened – the problem is the LLTNPA is not monitoring its planning requirements on an ongoing basis through construction with the result they are ignored. While this is a failure, in landscape terms, the Munro Society members were generally agreed that the main landscape concern is the track because the vegetation above the pipe, although not restored properly, is likely to recover quite quickly.

The Munro Society team had between them been up almost every 30m bump in Scotland and besides the hill chat, one of the pleasures of going out with them was hearing what such experienced hill goers thought about various aspects of the hydro development. I have rarely seen a constructed stone culvert in the LLTNPA hydro schemes as above. They approved. While the track at Ledcharrie is far too broad, increasing its impact on the landscape, almost every culvert pipe had been properly finished, (unlike the Glen Falloch schemes). Just why contractors are good at one thing or in one area but then fail totally in others is another question that needs to be asked. I suspect the problem is a lack of monitoring from the LTNPA to ensure consistent high standards. If the problem is lack of resources to do this, the answer is simple: re-direct resources away from chasing innocent campers and direct them to protecting our landscape. The impact of even the most irresponsible of campers is temporary, the impact of these track is, in human timescales, permanent.

Just upstream of the culvert though, Stuart Logan, Munro Society President spotted that this. No-one present thought that lining stream beds with concrete is acceptable (this was the first time I had seen this). How could this happen in a National Park?

Just upstream of the culvert though, Stuart Logan, Munro Society President spotted that this. No-one present thought that lining stream beds with concrete is acceptable (this was the first time I had seen this). How could this happen in a National Park?

The track above the culvert was also very poor, not only far too wide, but it had been lined with blocks which appear to have been created by the developer blasting through rock bands where the soil was shallow. The end result looked more appropriate for a quarry than a National Park.

Another thing I had not seen was the use of netting in an attempt to hold soil in place at the edge of a track. Here the netting has totally failed and filled with material that has slumped down the slope, a consequence of the bank/edge of the batter being too steep. On the top right you can see how soil and rock, which could have been used to help reduce the angle of the slope, has been left dumped on top of vegetation.

Another thing I had not seen was the use of netting in an attempt to hold soil in place at the edge of a track. Here the netting has totally failed and filled with material that has slumped down the slope, a consequence of the bank/edge of the batter being too steep. On the top right you can see how soil and rock, which could have been used to help reduce the angle of the slope, has been left dumped on top of vegetation.

On the downside of the track, below the scar in the photo above, the material excavated to create the track had been dumped on vegetation and no attempt has been made to restore this. The drainage ditch is a later addition bu,t instead of using the new turves to help restore the ground elsewhere, they had been left scattered on the neighbouring ground (large turf centre)

We had a good discussion about the main intake on the Ledcharrie burn. There was general agreement that the intake was well located being tucked below the level of the banks and surrounding ground and would not be visible from afar. There was debate about whether the rip rap embankment, in this case partially embedded in concrete, could have been designed better. I asked people about the concrete dam walls, pointing out the LLTNPA’s Supplementary Guidance suggests these could be faced in stone, although I had never seen this. Someone pointed out there was plenty of material available to do this from the old dyke behind the intake (centre of photo). So why not?

We then walked down the track a bit before heading up to the second intake which I had only realised was there because of the disturbed ground above the pipe. You could not see it from below and some of those present had doubts about whether there was a second intake – a really good sign! Again the visual impact of the intake itself was not significant in landscape terms, although the concrete walls could have been faced with stone.

The main difference in impact between the two intakes came down to the access track.

The first intake is hardly visible from 100m away except for the access track and turning area. (The burn slanting right to left has been diverted so it now enters the Ledcharrie burn above the intake. Another restoration failure can be seen centre far side of river – a patch of bare ground created because turves and topsoil were not properly stored).

The second, and more minor intake, has no access track and the ground has been completely restored and to a higher standard than that on either side of the track below. The line of the pipe and temporary construction track will probably have disappeared within a couple of years. Everyone thought this was great, its how hydro schemes should be.

This then raised the question of why access tracks are needed. I explained that the main reason to access the intakes is to clear them of vegetation. This can be done by a person with a rake. This raised the question of why, if maintenance staff are expected to walk to the second intake, couldn’t they also walk to the first intake?

This is what the LLTNPA’s Supplementary Guidance says should happen:

There was a good discussion too about how many people used the old path and whether footfall would increase as a result of the new track (we were passed by one walker). While people were generally appalled by the standard of construction of the track, there was a recognition that in terms of both landscape value and recreational use, this was not one of the most outstanding areas of the National Park. While we didn’t reach a definitive conclusion, there was a feeling that if the track could be restored to an acceptable standard, then leaving it in place in this instance was just about acceptable.

The problem though is the message that the LLTNPA is giving to developers. Glen Hydro Development Ltd is part of a suite of companies, all with the same Directors but split into separate companies (which both limits liabilities but means that only limited financial information is available as small companies are exempt from producing full accounts). Adam Luke Milner, besides being a Director of Glen Hydro Ledcharrie, is Director of 19 further companies, mostly hydro schemes, including ones at Kinlochewe, Chesthill, Fassfern, Glen Dessary, Loch Eil and Corrimony Farm. Richard Haworth is also a Director of most of these companies. If developers can get away with unacceptable standards in a National Park, they will try and get away with poor standards anywhere. Ledcharrie is yet another indication that making money, rather than care of the environment, is the main motivation of the people financing and benefitting from hydro developments.

An added complication at Ledcharrie, and a number of other Glen Hydro companies, is that on 1st March 2017 a Jan Tosnar was appointed Director and now appears to have a controlling financial interest in these companies (50-75%) through parallel companies called Renfin Ledcharrie, Renfin Chesthill etc based in Czechoslovakia. What appears to have happened is first the farmer/landowner agreed with a developer they could develop a hydro (for a rent) but then these schemes have changed hands and most of the profit is now not just being channelled out of the area, but out of the country. In other words these hydro schemes will create little economic benefit for the area but are leaving a permanent impact on the landscape. Our National Parks should be exposing these issues and engaging with local communities and recreational organisations to devise better alternatives.

What needs to happen

- I would like to see our National Park Authorities engage with people who care about the landscape about hydro schemes, both about where they might be acceptable but also in developing standards for how they are constructed and restored and thinking about how economic benefits could be retained in the local area. I know the Cairngorms National Park Authority has met with the Link Hill Tracks group, its time the LLTNPA started a similar engagement with a view to strengthening how it implements and enforces its Supplementary Planning Guidance. I would suggest a day out with members of organisations such as the Munro Society would be a good place to start.

- At Ledcharrie, the LLTNPA needs to make public what plans it actually agreed following the granting of planning permission and then enforce them.

How you can help

Munro Society volunteers are starting to monitor hydro schemes across Scotland and will feed the results of their surveys to Mountaineering Scotland who has agreed to take up issues with Planning Authorities. This is a huge task and they are looking for more volunteers. If you could help or have photos of hydro schemes outwith the National Parks please contact them athttp://www.themunrosociety.com/contact-us:

I have agreed to co-ordinate surveys within our National Parks, so if you have photos or time to contribute to that please contact Nick.kempe@parkswatchscotland.co.uk

A Plook in the Park.

That’s snappy 😉

This is an excellent and thorough post. It’s good to see an organisation like the Munro Society coming on board as debate on the hydro issue needs to take a more concrete shape (no reference to hydro design intended). Up until now it has been fragmented and lacked any kind of spearhead. I have been taking pictures of schemes I come across and passing them on, though I have to say I find it distressing when the area in question was once beautiful and has been wrecked. I wouldn’t voluntarily choose to walk into a hill along a hydro motorway – in fact, I go to great lengths to avoid it. Heights of Kinlochewe, for example, is one area of devastation I’ll be avoiding. Not sure how to bypass the Glen Affric schemes, though, with anything other than great difficulty. I agree entirely that LLTNPA should be allocating resources to the area of landscape monitoring and restoration. The standard of these schemes is appalling. Would a petition help?

Why should the LLTNP be required to divert their limited resources to dealing with the appalling mess left by a hydro company like Ledcharrie in Glen Dochart? The Park Authority have enough problems trying to deal with the utter shambles they have themselves created with the camping byelaws without having to divert resources elsewhere.

Surely the focus should instead be on the Directors of Ledcharrie and the multiple hydro companies that they appear to own? Are these fit and proper people to be involved in hydro scheme work? Should they be allowed to undertake any future hydro scheme construction contracts in Scotland? So long as the mess remains in Glen Dochart our national ands local politicians should be asking if we want any of these people involved in any future hydro work.

The NP Planning department are shirking their responsibility, what’s the use of carefully crafted planning consents designed to satisfy critics before it’s approved only to have applicants breach consent across the board and seemingly get away with it. Applicants can act with impunity by following the poor example of the Park Authority itself which does whatever it pleases, quite evidently so with all the breaches at the Loch Chon site and other issues with documents being hidden from view even before work started on developments making any public scrutiny impossible.

It outrageous that the Park Authority and the Planning Authority should breach their respective codes of conduct in demonstrating their stated ideals of openness and transparency are no more than fiction.

The planning department tells us it’s doing visits, at least according to their case study, where it explains how well the planning department are managing the additional workload of Hydro-schemes, where in reality, what we see on the ground is something else completely.

Their Planning Performance Framework 2015-2016 (the latest one available), states that:

“The forward planning of these site visits has enabled us to co-ordinate our visits with the relevant Ecological Clerk of Works (ECoW) and Landscape Clerk of Works (LCoW) on these sites, thus ensuring that each site receives the required standard of monitoring.” it would seem that policy is also failing. However you would think the two clerk of works could manage independently and get the job done, I suspect the these “clerk of works” either have not been employed on projects after January 2015 or they are just ineffective as would appear to be the the case judging by the state of Loch Chon.

As to the concrete they should be made to remove it, No Ecological or Landscape clerk of works would ever have sanctioned that.

The problems with small scale hydro are abundantly clear . However, the problems identified could be reduced significantly if a few simple steps were taken; these steps would not prove expensive. What is lacking is the will, politically and within planning auhtorities, to take them. Such steps include-

1planning authorities requiring that all exposed concrete is either dressed in locally sourced stone or banked up with earth and vegetated as approriate.

2) planning authorities ensuring that applications include fuller details regarding the construction of the tracks and restoration methods. Scant information is accepted too often. Planning authorities should also ask more questions regarding the need for permanent tracks as, in some instances, these may not be necessary. Planning consents should ensure that tracks are of the narrowest width needed and a vegetation strip down the centre should always be included; the latter reduces visual intrusion.

3) planning authorities should require applicants to advise them the moment the work is deemed to be finished and the former should prioritise immediate inspection. While it is acknowledged that authorities are under resource pressures, the number of hydro schemes is not that great. Where the work has not been completed as per the original application, enforcement should follow immediately.

The tracks are the aspect of shemes which is most intrusive in the landscape and the issue which is given the least attention at the planning and restoration stage.

If only the National Parks and other planning authorities were as analytical and incisive in their assessment and oversight of these schemes as Nick! It’s great to see colleagues in TMS being proactive and highlighting poor and malpractice. Well done.

Interesting comment from Nick on company structure. Dickins Hydro (proponent of the seven schemes of Glen Etive) has eight companies. One for each scheme, plus one for transmission, presumably anticipating a need for pylons to extract the power generated.

Concerning the Allt Fhaolain scheme, the Grampian Club has asked Mr Dickins for details of any mitigation measures in response to his request for a meeting only last week) and asked the Highland Council planning officer for a meeting to press our case for refusal. Neither have had the courtesy to reply as yet.