This post takes a critical look at the implications that the Scottish Land Commission’s “Legislative proposals to address the impact of Scotland’s concentration of land ownership”, published on 4th February (see here), has for our National Parks in the light of the purchase of the Kinrara estate on Speyside the week before.

The sale of Kinrara

It is just over two years since the Danish billionaire, Anders Povslen, quite openly purchased Kinrara House and the land immediately surrounding it (see here) for a reported £3m. Now the rest of the estate, all 3,767 hectares of it, including Lynwilg and seven other houses has been purchased anonymously for an unknown amount.

According to the Land Registry, the estate was last purchased for £3,514,850 on 29th July 2005. This means that if it was sold for the price tag of £7.5m, and taking account the earlier disposal of Kinrara House for £3m, the market value of Kinrara increased c£7m or tripled in just 15 years.

The Strathy reported (see here) that the buyer is likely to be BrewDog. Why BrewDog, the publicity seeking North East Scotland brewer, would want to keep the sale anonymous, when last year their purchase of land in Glen Orchy to plant trees was openly reported (see here) is unclear. But if true, it appears the purchase could have been funded by BrewDog’s Equity for Punks Crowdfund initiative which was launched last September and whose initial target was to raise, wait for it…….£7.5m (see here).

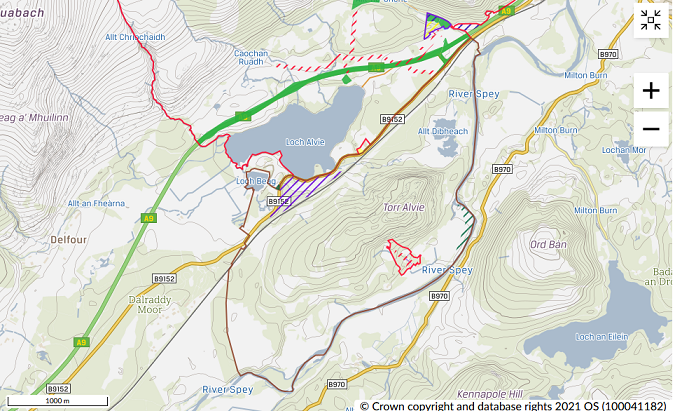

The Land Registry was intended to improve the transparency of landownership in Scotland but two weeks after the sale all it records for Kinrara is that “We are processing an application which, once registered, may change the information shown on this title” (see here). This does not appear just a temporary glitch. Two years later, the detail of Povlsen’s purchase of Kinrara House doesn’t appear to have been made public either, although the estate maps appear to be in the process of being updated:

In 2017 the Scottish Government published a Land Right and Responsibilities Statement (see here), as required by the 2016 Land Reform Act, which clearly said:

“There should be improved transparency of information about the ownership, use and management of land, and this should be publicly available, clear and contain relevant detail.”

Anonymous purchases should, therefore, have been a thing of the past but four years later are alive and well, even in our National Parks. I suspect lack of resources at the Land Registry is responsible.

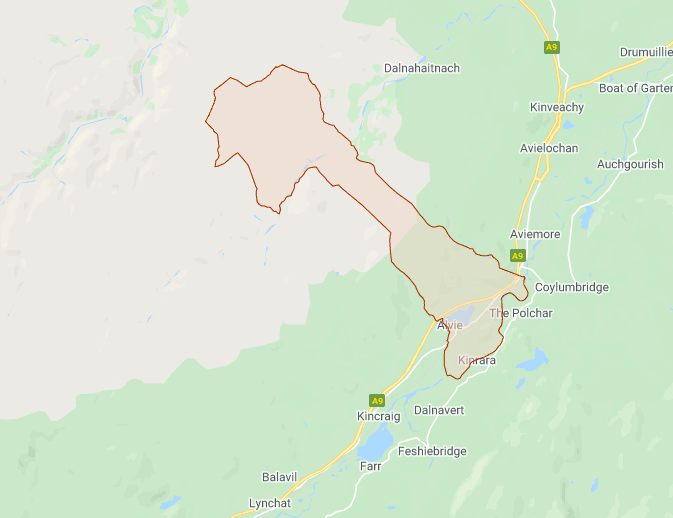

The CNPA, which to its credit publishes maps of estate boundaries and has encouraged estates to publish statements about how they manage their land (see here) , has not updated the map for Kinrara (top) to reflect Povlsen’s purchase. Neither estate has provided a management statement.

If BrewDog has bought Kinrara, it could be an interesting purchase, bringing a different type of landowner into the market, one apparently wanting to offset their carbon emissions rather than shoot and kill wildlife. If they, or any other owner, intend to end muirburn and reduce deer numbers to allow woodland to regenerate, that would be a good thing. Equally, however, a “productive grouse moor with 10 year average of 476 brace”, the “challenging, high bird pheasant shoot” and salmon fishing on the river Dulnain might prove very attractive for the purposes of entertaining corporate clients .The problem is neither the public nor the Cairngorms National Park Authority would appear to have any idea of the new owners’ intentions and, more specifically, whether they are committed to furthering the statutory aims of the National Park. What this shows is the way the land market works at present is simply not in the public interest.

The Scottish Land Commission’s legislative proposals

In March 2019 the Scottish Land Commission (SLC) published a report on the issues associated with large scale and concentrated land-ownership in Scotland (see here) which included a number of proposals for reform. After being given the go-ahead by the Scottish Government, 22 months later the SLC has expanded on three of the suggestions in the original report but states that “significant work remains to be done to develop the proposals into fully functional legislation and [the SLC] anticipates that extensive consultation with stakeholders would be required to achieve this.” The Discussion Paper also recognises the need for “more fundamental policy reform, probably including changes to the taxation system”. The speed of land reform in Scotland is glacially slow.

The explanation for this hands-off approach lies in free-market ideology and the SLC’s assumption that the private operation of the land market will deliver the public interest except where power becomes too concentrated:

“The issues associated with concentrated power in localised rural land markets have close parallels in mainstream economics and can result in adverse effects similar to those associated with corporate monopolies. Unlike other markets however,there are currently no mechanisms for regulating these effects in the land market to ensure that it operates efficiently and in the public interest.”

The land reform agenda is thus limited to a bit of tinkering, with the SLC believing that almost all issues can be addressed through voluntary mechanisms. (although you would not guess this from the outrage with which Scottish Land and Estates responded to the proposals (see here)).

The SLC’s first proposal is “A requirement for land holdings over a defined scale to prepare and publicly engage on a management plan”. They claim this is “a practical mechanism to moderate the power of ownership by ensuring communities are more involved in influencing and benefitting from land use decisions” and “It is envisaged that enforcement could be based on a range of cross compliance mechanisms, such as being a pre-requisite for access to regulatory consents and fiscal support”. In other words if a landowner fails to produce a land management plan they could be blocked from receiving rural grants or even potentially from being granted planning permission.

The proposal is very unlikely to work. It is focussed on involving local communities when many remote local communities are totally dependent on the local landowner and therefore unlikely to be able to speak out about the power of the local laird. It excludes communities of interest, whether people concerned about the landscape, conservation or wildlife, and there is no mention of the role of statutory authorities, like National Parks in these management plans. If a sporting estate, for example, choose to continue to carry on with their destructive practices without seeking grant support they will be free to do so. The evidence suggest most estates are very reluctant to publish information, whether this is those like Kinrara which have ignored requests from the CNPA to publish management statements or those in the East Cairngorms Moorland Partnership, which are supposed to be working closely with the CNPA, which continue to refuse to publish information about what they are doing (e.g on hare culls, stink pits, muirburn, trapping). Moreover, how anyone could prove that local communities had either influenced a land management plan or benefitted from it is not explained.

In theory there could be considerable overlap between the SLC’s proposed management plans and proposals developed by the Scottish Government to introduce licensing of grouse moors and implement the recommendations of the Deer Working Group, both of which have considerable significance for the Cairngorms. But the words “grouse” and “deer” don’t even appear in the Discussion Paper which has nothing to say about either climate change or the nature emergency and appears completely divorced from reality.

The SLC’s second proposal is for “A statutory review mechanism framed within the principles of Scotland’s Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement to be a practical means of intervention to address adverse impacts of concentrated ownership in a specific land holding where these occur”. The scope of this appears far more limited than the proposal for Management Plans but, having outlined a complicated process full of pitfalls to be exploited by lawyers, the SLC even swithers about enforcement:

“The Land Commission is of the strong view that some form of enforcement mechanism would be required to ensure compliance with reviews; however, in principle it would be possible to implement reviews without any enforcement mechanism”.

So which is it?

The third proposal is most relevant to the Kinrara sale: “a public interest test for significant land acquisition, at the point of transfer, to test whether there is a risk arising from the creation or continuation of a situation in which excessive power acts against the public interest.” This test is not about HOW the buyer intends to manage the land, for example whether this might be in accordance with the statutory aims of our National Parks, but rather whether the acquisition might result in excessive power. According to the SLC:

“It may be reasonable to expect that, for example, holdings over 10,000ha would always be in scope, while those under 1,000ha would always be exempt. The Land Commission does not have a firm view as to exactly where a threshold might fall within this range and proposes that this should be the subject of [yet more] further consultation and discussion”.

This is remarkable. Kinrara Estate is according to the Galbraith sales pitch “some 9 miles long and 3 miles wide at its widest point” but because its only 3,767 hectares the SLC has no firm view as to whether its sale should be subject to a public interest test or not. On their 10,000 Hectare criteria, only the largest estates in Scotland would be subject to the test, with no consideration given to the significance of a piece of land, whether it’s in a National Park, protected by statutory conservation mechanisms or offers opportunities for local communities. In the market world of the SLC the only thing that matters is the “concentration” of ownership.

At least the SLC does recognise that ownership of land can transfer ownership in ways other than open market purchase including: “Private sale; Inheritance; Sale of shares in the controlling company resulting in a change of controlling interest or majority shareholder; Appointment to, or change in, trusteeship; Creation of an option agreement over land” and this needs to be addressed in any legislation. While limited in scope, what the proposal could therefore do is create a power to break up the largest landholdings in the Cairngorms National Park like Blair Atholl Estates (58,962 ha) and Invercauld (43,600 ha), both of which are operated as family trusts. If the SLC, however, believes this desirable, why not do this now rather than waiting until an estate changes ownership?

The public interest and Kinrara

What the SLC’s proposals won’t do is address the public interest questions that are raised each time large chunks of land exchange hands. For example, assuming BrewDog have bought Kinrara and it’s with the intention of planting trees as a means of off-setting carbon, there are still a significant number of public interest questions that need to be addressed:

- Do they intend to plant any trees in the Dulnain catchment, the larger part of the property, which holds significant accumulations of peat and important remnants of Caledonian Forest there? This native pinewood, one of the most important ancient woodlands in the Cairngorms, has been gradually expanding out from Kinveachy through natural regeneration – a success story – and the whole glen has the potential to regenerate naturally. The new owners could support that, which would be a wonderful thing, but they could equally well degrade this natural expansion through planting.

- Are they as committed to deer control, which is essential to enable natural regeneration of the Caledonian Forest, as they are to tree planting? Does deer control and increasing culls from current levels (only 20 stags and 23 hinds) fit their public image?

- Will BrewDog be prepared to stand up to other local landowners who may object if Kinrara increase deer cull levels. With much of the hill ground between Laggan and Aviemore subject to serious overgrazing by deer it is obvious that other landowners are failing to ensure that natural habitats are restored properly.

- Will BrewDog be committed to ensuring that any tree planting on the Badenoch side of the estate is done without fencing and without use of plastic tree guards?

- Will they protect native wildlife and stop importing pheasants and partridge for shooting?

- Will they use the houses included in the estate sale for people to live locally or alternatively do they plan yet more holiday lets?

- The list could go on……………..!

The problem with the land market currently, and with the reforms proposed by the SLC, is that the potential owners of large areas of ground important for nature, carbon, outdoor recreation or local communities, aren’t even asked to consider these issues prior to buying a property, let alone come up with plans. Unlike the housing market, where no-one with grand plans would buy a house before checking first what might be acceptable to the Planning Authority, you can buy a large chunk of land in our National Parks without considering the issues or talking with the National Park Authority. The SLC’s legislative proposals will change none of that and are more or less completely irrelevant to changing how land is Scotland is actually managed, whether or not this is in our National Parks.

Sadly in Scotland there appears to be not a single Public Authority that is prepared to challenge the power of landowners, a pre-condition for any effective action being taken to tackle the climate and nature emergencies.

The purchase of Kinrara estate by BrewDog is intriguing. There is no indication that they will pursue traditional land use activities and so there is the potential for a new and refreshing approach. And, as neighbours of Anders Povlsen, the owner of both Glenfeshie and the remainder of Kinrara, they will soon see how the cessation of muirburn plus a severe reduction in the red deer population is the best and quickest way to achieve their climate change mitigation objectives. The natural regeneration of trees and shrubs will follow, along with tree planting, where appropriate. This is also an estate that will be very much in the public eye, adjacent as it is to Aviemore. Given the extensive use of their land in recent weeks for some of the best ski touring in Scotland for several decades, the new owners can be sure that the outdoor recreation community will want to know what is being planned.

Brewdog,with their brand image, will want to make the right choices here.

As Dave says, they are very much in the spotlight, and will hopefully be influenced by their more progressive neighbours. There is even scope for a new, appropriately named, beer in celebration.

An excellent and thought provoking article which exposes the lumbering of the Land Commission. The impression is that the Land Commission is just floating out ideas, without any real leadership or attempt to link these ideas to climate change, moorland monoculture issues or the planning framework.

There is certainly a need for more transparency in ownership structures and transfer of larger land holdings. I believe, however, that concerns over the holding of large estates under single ownership are often misplaced. What is of importance is to what use these large landholdings are put. Anders Povlsen and some of his neighbouring estates have in many respects shown the way that rewilding of the Highlands with the large improvements in biodiversity can be achieved, with little or no Government intervention or support, whereas all the ‘befriending’ of the East Cairngorms Moorland Partnership by CNPA and others has achieved a mass of words and verbal intentions, but very little on the ground.

Hopefully, if BrewDog has purchased the Kinrara estate, as Dave Morris says, maybe they will look to what Anders Povlsen has done and commence a major and positive change of direction for this estate.

The Scottish Government, with the involvement of the Land Commission and other public bodies, needs to urgently focus on introducing major restrictions on grouse moorlands and through policies, example and legislation encourage the preservation of peatlands, reverse the desecration of our uplands with the proliferation of hill tracks and require land management plans to greatly improve the biodiversity found on these large estates, including better enforcement of raptor conservation and much more stringent licencing over predator control.

What I find uncomfortable is how we all have to wait and see how new owners of very large areas of our country and landscape are going to manage it. Are they rewilders? Are they going to stop killing wildlife for fun? This is just another example after the change of ownership of Kildrummy in Aberdeenshire. The anticipation and speculation about whether the new owners are going to “do the right thing” is breathless.

If however National Park status meant anything, nature and landscape conservation would be written into the long term management of this land and not at the whim of any new owner. Is there anything to stop the next owner of Kildrummy or Kinrara from deciding to intensively manage for grouse?

Just because owners of large, some would say ridiculously large, areas of land are managing that in a way approved by ‘us’, doesn’t mean that the concentrated land ownership pattern, almost unique to Scotland is right.