I was away up near Ullapool last week. Driving up the A9 the snow had helped pick out the muirburn in Glen Truim, north of the Drumochter and Dalwhinnie. Much of the hillside below the telecommunications mast, which is on land that appears to be owned by the North Drumochter Estate, would quickly regenerate as woodland if it was not for the muirburn.

The snow also helped reveal how fires have been started immediately adjacent to patches of woodland; in its way a very skilled job but hardly prudent. It would take closer examination to determine whether any of the more developed scrub had been destroyed by the burning but at best the muirburn on this slope is releasing carbon into the atmosphere, polluting the air and preventing any further woodland development.

There was a similar view on the eastern side of Glen Truim on land that appears to be owned by the Phones, Etteridge and Cuaich Estate. Although there is a river, railway and the A9 between it and the woodland on the other side of the glen, seed from trees can blow for miles in snow and frozen conditions. That helps explain why woodland has developed in fenced areas all along the A9. Muirburn prevents woodland regeneration whether trees are visible or not.

Sadly, the Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) included no proposals to address the destructive impact of muirburn in their draft National Park Partnership Plan. Indeed they stated in their draft plan (see here) that if they reach their targets “over three quarters (77%) of the Park will still be open habitat by 2045”, i.e much of the land in the National Park will continue to appear like that in these photos – a disgrace.

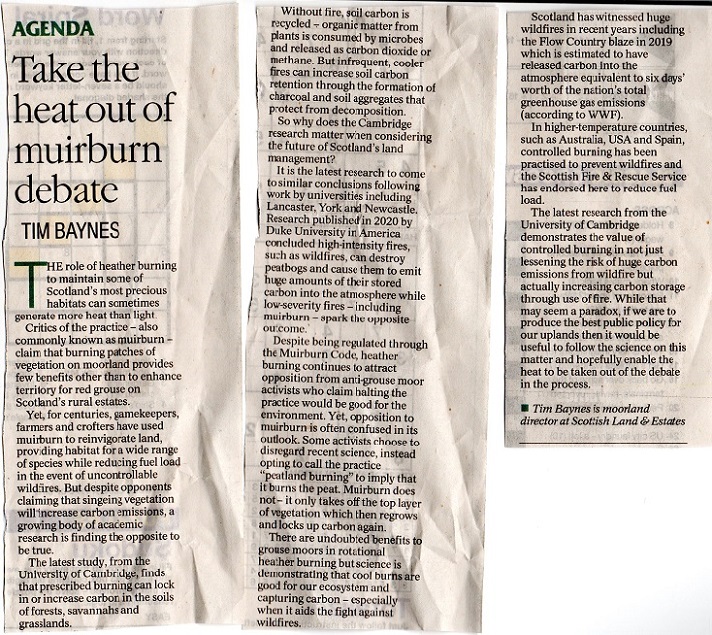

While the CNPA still appears firmly under the thumb of grouse moor interests led by the Royal Family (see here), there are signs that landowning interests are starting to feel the heat from the public, hence this piece which appeared in the Herald last Thursday:

While Mr Baynes did record that the research was about the impact of burning on the soils of forests, savannahs and grasslands, he then applied the findings to moorland, a completely different habitat. It appears that the temptation to cite research from Cambridge University in defence of grouse moor management proved too great to resist.

While Mr Baynes did record that the research was about the impact of burning on the soils of forests, savannahs and grasslands, he then applied the findings to moorland, a completely different habitat. It appears that the temptation to cite research from Cambridge University in defence of grouse moor management proved too great to resist.

But if you read the actual research findings (see here) it should be very clear that they don’t provide support for Mr Baynes’ argument.

“Fire stabilises carbon within the soil in several ways. It creates charcoal, which is very resistant to decomposition, and forms ‘aggregates’ – physical clumps of soil that can protect carbon-rich organic matter at the centre. Fire can also increase the amount of carbon bound tightly to minerals in the soil.”

Comment: Peat, like charcoal, is resistant to decomposition but for very different reasons – it is so acidic that the microbes and fungi that help form other soils can’t survive. Moreover, as peat develops the minerals that are found in other soils are noticeable by their absence. There are serious reasons to doubt therefore that the process of “aggregate” formation and mineral binding described in the research applies to large areas of land that are currently managed as grouse moors.

“Ecosystems can store huge amounts of carbon when the frequency and intensity of fires is just right. It’s all about the balance of carbon going into soils from dead plant biomass, and carbon going out of soils from decomposition, erosion, and leaching,” said Pellegrini.

Comment. The reason why peatland is so important for storing carbon is that “dead plant biomass” doesn’t degrade in the normal way releasing carbon into the atmosphere but is preserved in the highly acid environment. Peat has the potential, therefore, to lock up carbon like no other soil and the processes which control peatland development are not comparable to the processes that affect the habitats considered in the research.

“When fires are too frequent or intense – as is often the case in densely planted forests – they burn all the dead plant material that would otherwise decompose and release carbon into the soil. High-intensity fires can also destabilise the soil, breaking off carbon-based organic matter from minerals and killing soil bacteria and fungi.”

Comment. Under muirburn regimes land is generally burned around every 12 years in order to provide a heather-mix which maximises the numbers of red grouse: enough young heather for them to eat and enough older heather to provide shelter and cover from predators. Whether “intense” or not, muirburn consumes a large proportion of the dead plant material that would otherwise go to form peat. It effectively prevents both peatland formation or, in areas of peaty soils more favourable to trees, woodland formation.

“Without fire, soil carbon is recycled – organic matter from plants is consumed by microbes and released as carbon dioxide or methane. But infrequent, cooler fires can increase the retention of soil carbon through the formation of charcoal and soil aggregates that protect from decomposition.”

Comment. In peatland very little of the organic matter in plants is consumed and released as carbon into the atmosphere as part of the carbon cycle. Therefore, whatever implications the research has for increasing the proportion of carbon in the soil in dry climates and grassland, there are good reasons to doubt that any are applicable to grouse moors. Moreover, because of the high rainfall in Scotland much of the residual carbon from muirburn is likely to be washed away before it can be trapped in the roots of new plant growth.

The scientists say that ecosystems can also be managed to increase the amount of carbon stored in their soils. Much of the carbon in grasslands is stored below-ground, in the roots of the plants. Controlled burning, which helps encourage grass growth, can increase root biomass and therefore increase the amount of carbon stored.”

Comment. There are multiple uses of the word “can” in the scientists’ summary of their research: whether burning might lock carbon into soils depends on lots of variables. While muirburn is still used by sheep farmers to increase grass growth, on grouse moors it is used to promote grouse-food, heather, at the expense of other plants. On bogs, the roots of heather and other plants forms the acrotelm, the vegetational layer that sits above the peat. This is generally saturated, because the roots of the plants help hold in the water and that helps prevent plants decomposing in the normal way, but burn that off and you are releasing carbon which might otherwise become peat.

Mr Baynes’ claim that “muirburn……….only takes off the top layer of vegetation which then regrows and locks up carbon again” is wrong. Peatland development takes a long time and if you are constantly burning off the top layer you are preventing it from developing. Moreover, regular muirburn periodically exposes the surface of the peat and subjects it to other erosional processes, such as desiccation, frost heave and trampling, which then releases stored carbon into the atmosphere.

If muirburn, a practice that has been conducted for a couple of centuries, is necessary to protect peat from more intense fires as Mr Baynes claims, it is very difficult to explain how peat bogs ever developed in the first place. All should have all gone up in smoke as a result of fires caused by lightning or humans. The reason that hasn’t happened is peatland is fundamentally a wet habitat – the peat raises the water table – and very occasional fire is unlikely as a consequence to do much damage. But keep burning the habitat and the surface water drains away allowing the surface of peat to dry out, making it far more vulnerable to fire.

Muirburn therefore (along with overgrazing) helps to explain not just why moorland hasn’t developed into woodland, but also why the wetter areas have not developed into peat bogs. That is why it is so important that muirburn is banned not just in our National Parks but across Scotland.

Far from taking the heat out of the muirburn debate, such as it is, Mr Baynes has added fuel to the fire. Rational debate with the owners of grouse moors has been impossible for a very long time. As D.N. McVean and J.D.Lockie put it in “Ecology and Land Use in Upland Scotland” which was published in 1969:

“the practice [of muirburn] has become so deeply ingrained as to be almost an article of faith, and any attempt at dispassionate re-assessment is not well-received” .

Fifty years later most of the arguments of McVean and Lockie about the impact of muirburn still apply but the difference now is the debate is far more public. As the grouse moor managers resort to ever more desperate arguments in the face of public criticism and the climate and nature emergencies, their selfishness – putting grouse shooting before the public interest – becomes ever more obvious. Driven grouse shooting is as hypocritical as the parties held during lockdown at No 10. The Scottish Government should be banning muirburn everywhere.

He is a master of cherry picking spin. His assertion is Johsonesque in its truth.

None of our vegetation is fully adapted to a natural fire regime. What they create is based on species which can quickly recolonise post the fire. All other species are prevented from regenerating or are out competed. The vegetation community that they create is biodiversity poor and lacking in structure. The lack of plant biodivesity limits the animal biodiversity. In addition to the mamals and lizzards that it illegally kills. Burning is an act of deliberate sterilisation.

One small thing that the National park could do (if its not curbing the extent of muirburn) is to monitor compliance with the muirburn code. In the photos you use to illustrate your blog most of the areas muirburn would not comply with the code. It seems that SNH and Scottish Government cant be bothered checking so maybe the Park could show an interest?

Hopefully one day muirburn will only be carried out under licence…..so it will have to be monitored by somebody.

Great points about the Moorland Code. The CNPA has apparently been working with the estates in the East Cairngorms Moorland Partnership to “improve” muirburn practice but has not, as far as I am aware, produced any report to demonstrate what impact that has had. In my view our Public Authorities will never have enough resources to monitor whether estates are abiding my good practice – there are similar issues with trying to monitor whether sporting estates are meeting targets for deer numbers – and as a result a licensing scheme for grouse moors is unlikely to have much impact unless also accompanied by a ban on muirburn.

Most of the estates should be producing a muirburn plan to support their SRDP applications. It would be possible to link these plans to the proposed licence. However, the licence should raise the standard required for these plans. Firstly there should be a baseline survey founded on a strict interpretation of the code. This would identify all of the sensitive soils/habitats and indicate the remaining area where burning might be accptable. This would remove peat soils, screes, steep slopes scrub, woodland, summit heath, watercourses skeletal soils etc from potential burning. In the greatly reduced areas where burning might be acceptable, they would then have to illustrate their planned rotation and out line other key elements like available staff resource etc. If these plans are public (why not?) then anyone could check compliance. But the SG (or the Park authority) could do a simple annual check for burning outwith the approved area using rapid automated analysis of sat photos.

Many thanks for this. It’s perhaps worth adding that the paper is essentially a literature and metastudy which them proposes a pretty general model for the circumstances in which burning could add or subtract carbon. As you say, there are a lot of ‘can’s in it, and it is in the nature of the paper that no specific examples are cited. Rather, it points to some vegetation and soil types where soil carbon might increase inder some burning regimes and others where that would be unlikely. Peat is scarcely mentioned except to put it firmly in the ‘unlikely’ category, almost directly contradicting Mr Baynes’ wishful thinking. There is a much fuller review of the evidence related to peat at NERR094, easily found by googleing that reference.

I understand that the lead author does not especially want to get involved in public controversy, which is understandable, but has written to those misrepresenting the research findings. I fear he may have a lot of letters to write as I don’t suppose we have heard the last of this.

The full paper is behind a paywall but a free copy is viewable (but not downloadable) here: https://rdcu.be/cDLSa

This twitter thread might be of interest, in which the authors of the discussed paper specifically say that their paper does not refer to peaty soils: https://twitter.com/baird_andy/status/1480487285430890496

From two of the authors of the paper: ‘The interpretation has been frustrating, especially because (as you quote) we explicitly talk about how our framework is limited in peaty systems’, and ‘This review was not focused on peatland soils and we made no claims about these concepts in peatlands. Strange that the paper would be misused in this way.’

Whether there is some justification for muirburn on non-peaty soils from a pure carbon sequestration perspective is another question – but it is worth pointing out that that a very significant proportion of the Cairngorms, Monadhliath, Donside and Angus glens have peaty soils in one form or another, as can be seen from Scottish Government’s maps: https://map.environment.gov.scot/Soil_maps/?layer=10

To the casual observer, it would seem that there is in fact a bit of a correlation between areas with peaty soils and areas where grouse moors are a dominant land use…

The observation about how much tree cover has reasserted itself along the margins of major roads through this region is the most significant aspect of all this. It is self evident that where little grazing pressure remain, and no one interferes for many years trees will return . (However, I found it a bit sad yesterday to come across a works team busy clearing “sight lines” around bends along the verges of the A 828 . Tuesday’s team comprised, traffic lights 4 vehicles and approx 5 men busy all day. The scandal was that they were equipped so poorly, with hand tools and a very small self propelled chipper. In today’s world arguably the most inefficient and costly tool set for roadside maintenance. . Their day’s achievement about 100 mtrs. This is unaffordable.

The Autobahn authority in Germany, and those equivalents in other central EU states, years ago developed a single truck based machine that cuts, chips and jets debris back into its own container . It can move at walking pace and may clear a strip up to 2mtrs from the carriageway in a single pass. What more proof is required to confirm that European woodland trees will reappear where ever grazing pressure , and thoughtless fire raising for selfish leisure reasons , is absent…?

This research paint a different picture on the subject on controlled burning.

https://www.gwct.org.uk/wildlife/research/upland-biodiversity/low-severity-fires-can-improve-carbon-storage-in-peatlands/