There are lots of good aspirations in the draft Cairngorms National Park Partnership Plan (NPPP), which is out for public consultation until 17th December (see here), but at the heart of its plan for nature is an unambitious target for carbon emissions. The effect of this will be to allow unsustainable management of land to continue unchallenged and undermine actions designed to enable the highly damaged natural environment in the National Park to recover. This post takes at the issues.

The Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA)’s carbon emissions target

The CNPA’s draft NPPP starts well (p8):

It then immediately undermines the carbon negative outcome by adopting the same target date for net zero as the Scottish Government does for the whole of Scotland:

Following the pack is not acting as an exemplar and will undermine the possibility of Scotland meeting its net zero target. The reason for this is that the Cairngorms National Park covers an area of 4,528 square kilometres and in 2018 had a population of 18,264 – approximately four people per square kilometre. That compares with Glasgow which has a population density of c3,400 people per square kilometre. If government is really serious about achieving net zero, we need the land and sea around Scotland to absorb far more carbon that it does at present. Key to that is creating conditions in the countryside in which peat and other soils and increased woodland cover takes carbon out of the atmosphere. There is far less opportunity to do that in urban areas. (I am lucky enough to have a small organic urban garden which has been absorbing carbon for 20 years but its no match for a similar area of undamaged peat bog). Our National Parks should be taking a lead on this by aiming for net zero by 2030 – it is a climate emergency after all.

The peatland and woodland restoration targets in the NPPP

Given the recent interest by businesses such as BrewDog (see here) and Standard Life Investments Property Income Trust (see here) in buying up land in the Cairngorms, ostensibly for carbon offset purposes, one might have expected that the NPPP would set ambitious targets for peatland and woodland restoration.

The draft NPPP, however, states that peat in the Cairngorms is still being lost quicker than it is being formed:

“The degraded peatlands in the mountain areas are also emitting carbon dioxide, adding to the emissions in the National Park” before continuing “However peatland restoration projects are underway to bring peatland habitats back to functioning carbon sinks”

The CNPA’s draft NPPP target is that “A minimum of 35,000 ha peatland restored by 2045″. This is out of “90,000 ha of degraded peat”, all of which is releasing carbon into the atmosphere. Just when peatland within the National Park is expected to start storing more carbon than is being released and make a positive contribution to addressing global warming is not stated.

Seen within the context of the Scottish Government’s overall target that 250,000 ha of peatland, funded through a £250m programme, should be restored by 2030 (see here), the CNPA’s aim to restore 35,000 ha by 2045 looks remarkably unambitious, particularly when according to the NPPP the National Park contains 15% of all the bare peat in Scotland.

There is a similar target for woodland restoration: “A minimum of 35,000 ha of new woodland cover created by 2045“. The NPPP describes this as ambitious “When we achieve these ambitious targets, over three quarters (77%) of the Park will still be open habitat by 2045″. That means 23% of the National Park will be covered in woodland in 23 years time, compared to the average woodland cover in the EU which according to Forest Research was 38% in 2015 (see here). Is that really the best our largest National Park could do?

The barriers to changing land-use in the Cairngorms to absorb more carbon from the atmosphere

These unambitious targets are not the fault of staff but a consequence of the power of sporting estates within the National Park This is encapsulated in the weak proposals to address high deer numbers and muirburn, the two most significant factors that impact on the natural environment in the National Park.

At first sight the proposals to reduce the density of red deer in the National Park may appear a major step forward given the 10 deer per sq km target that is normally quoted :

But we know now from the experience of Cairngorms Connect and Mar Lodge Estate that only when deer numbers are reduced to around three per sq km or lower that natural woodland regeneration starts to take off. Five deer per sq km would certainly be an improvement on the current situation. It might even stop further damage to the natural environment and the leakage of historically stored carbon out into the atmosphere. But it will not be sufficient to enable nature to regenerate and begin to extract carbon from the atmosphere. And this, remember, is supposed to be a climate emergency.

But it’s worse than that because the target is an average of 5-8 deer across the 4,528 sq km of the National Park. There are some grouse shooting estates like Delnadamph, which is surrounded by an electric fence and owned by Prince Charles, where there are no deer at all. And then there are the large areas of land around Glen Feshie managed by Wild Land Ltd where deer numbers are less than 2 per sq km. What this means is that most of the sporting estates whose primary interest is deer stalking could continue to have over 10 deer per sq km on their land and the CNPA will still meet its targets. This lets the sporting estates with high deer numbers off the hook. In doing so, the CNPA is also creating endless expense for conservation owners like Wildland Ltd, the National Trust for Scotland, RSPB and Kinveachy who are trying to reduce deer numbers but are continually faced with incursions from neighbouring estates with far higher deer populations.

The draft NPPP, by adopting the Scottish Government’s current policy position on muirburn, provides a similar get out clause for grouse moor owners

Muirburn not only releases carbon directly into the atmosphere, it prevents peatbog and woodland formation. Permitting muirburn in areas where peat is less than 50cm deep would allow the owners of grouse moors to continue to manage most of their land as they do at present, using the very techniques that have degraded so much of the land in the National Park.

Confusingly, however, there is also an action under A6 to “Investigate use of CNPA powers to regulate fire and develop approach within the Park” which suggests the CNPA might be considering a tougher approach than the national licensing scheme. That would be welcome because if intensive grouse moor management is allowed to continue, it’s not just the Cairngorms National Park but the whole of Scotland which will fail to become net zero.

With the Scottish Government’s plans for net zero being so dependant on the untested technology of carbon capture, which have now collapsed in the wake of the UK Government’s decision not to fund the Acorn Scheme off Aberdeen, protecting peat should be more important than ever.

Reducing other carbon emissions

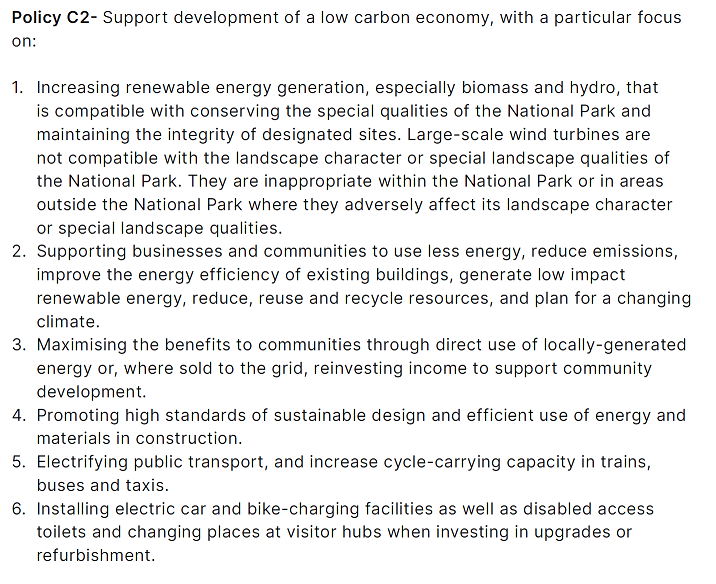

The NPPP is stronger on what needs to be done to reduce carbon emissions that are not related to land-use. It correctly identifies most of the main issues, for example:

These are worthy aspirations, if rather woolly – “high standards of sustainable design” is not the same as carbon neutral which should be a requirement for ALL new buildings. They are also now possibly out of date as a result of the publication of the draft fourth National Planning Framework yesterday (see here). But they will remain just aspirations, more policy “bla bla bla”, without investment. There is no mention of where that might come from because to do so would mean challenging other powerful vested interests.

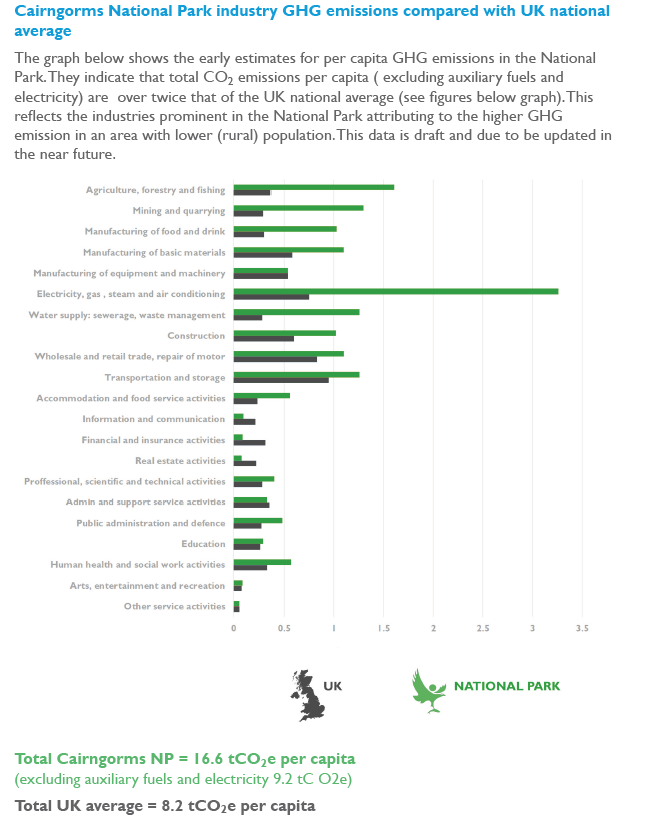

The excellent factsheet on climate change (see here) reveals that green house gas emissions per capita in the National Park are twice the UK average:

If this cannot be tackled through direct investment in carbon efficiency measures, it provides even more reason that the areas of land which are currently managed for sporting purposes are allowed to re-wild and absorb carbon through developing woodland or peatland.

What needs to happen

This critique has been based mainly on the information provided by the CNPA in the draft NPPP and the accompanying factsheets. CNPA staff deserve great credit for assembling/researching the information and making it public. I am sure many people working for the CNPA will know the information doesn’t support many of the objectives in the NPPP and that the plan itself does not go far enough. But to go any further without political support would be very risky. In Scotland’s conservative political environment, even talking about an average of 5-8 deer per square kilometre risks being branded as dangerous radicalism.

The CNPA also deserves credit for considering carbon emissions across the National Park as a whole, unlike the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority (LLTNPA) which, after a long period of climate complacency (see here), made this commitment: “By 2030, we will be a net zero emitting organisation. This is our Mission Zero” (see here)”. The CNPA does not even mention its own emissions in the NPPP – they are trifling in the scheme of things – even though they have been taking action to reduce them for far longer than the LLTNPA: “The Cairngorms National Park Authority (CNPA) has always strived to be as ‘green’ as possible has monitored its carbon footprint since 2007/08. In a decade, the organisation has managed to reduce its carbon emissions by 40% from 150 tCO2e to 90 tCO2e in 2017/18” (see here). The LLTNPA’s net zero target shows not an iota of concern for what is happening across that so-called National Park, whether this is the impact of overgrazing or industrial forestry practices on carbon emissions or the energy being consumed in the extraction of tiny amounts of gold from the Cononish mine. Far better the outward-looking CNPA than the blinkered LLTNPA.

While it’s important to acknowledge such positives, the world is at a tipping point and we need organisations that will be far braver and are prepared to take radical action. The CNPA is not there yet but the NPPP consultation provides an opportunity for the public and conservation-minded organisations to demand it adopts far more ambitious targets for net zero, peatland restoration and woodland restoration, and along with that a plan of action to make it all happen.

The future primary role of upland management in Scotland, in our climate emergency, should be to capture carbon through ecological restoration. In the Cairngorms national park this requires deer numbers to be reduced to around 5 per sq km and for the Scottish Government to stop the financial predators from getting their hands on huge chunks of land for tree planting, for BrewDog, Standard Life and others. Tree planting should be done elsewhere, where existing soils are devoid of organic matter. Ecological restoration in the upland sections of the national park simply requires proper control of grazing plus a cessation of muirburn.

Well done the CNP, they have managed to reduce the local carbon footprint in ways no one would ever have thought of, 20 street lights cut down in the middle of Aviemore years ago after one fell over and landed on some cars at the Railway station and never replaced, almost pitch dark and unsafe for pedestrians and cyclists in the busiest part of the Village, or perhaps allow Hundreds more house to be built and kill the local community, houses and flats for airb@B but as long as they are green properties.

Not sure to be honest if any of these things that are important to local people in Aviemore are CNP responsibility, but surely they could get things sorted.

There is not one person i know who was living here long before the CNP that won’t want to get rid of the whole park status, costing tens of millions it has made everything…. worse for locals.

I’m sure there is a great deal of research on how to limit the oxidation of peatlands carbon. Flash floods, windier conditions, less cold storage under frost and snow, hotter. All these factors must be peat eroding, carbon dioxide enhancing.

I was up on A Chailleach above Newtonmore a couple of days ago. Eroding peat is very evident on the western facing slopes of the ridge to the east above 600m. That erosion isn’t due to burning. In my 6 hour walk quite often scanning the hill for eagles I only came across 2 deer. I’m not sure how greatly deer are considered responsible for peatland damage.

Authorities like CNPA often seem to me to put a lot of effort into publicizing their positive actions like peat protection but perhaps not so much into informing as to the complexity of such tasks.