I returned from the Vanoise to the depressing news that a white tailed eagle had disappeared (see here) and SNH had issued a license to cull ravens in Perthshire (see here for fine piece by Chris Townsend) or (here). (You can sign the petition to SNH against the raven cull here). While both events took place/affect land outwith our National Park boundaries, they could have just as well taken place within them. A complete contrast to the Vanoise National Park.

This was created in 1963 to save the Ibex from extinction in the French Alps and originally its main purpose was to protect wildlife. Later on, the National Park was also given duties to protect the cultural heritage of the mountains and to support sustainable economic development – so its current objectives are not very different to our two National Parks. The way the Vanoise National Park puts these objectives into practice, however, is very different to our two National Parks and unlike in our National Park wildlife clearly and unambiguously comes first.

The most important difference in the way that the Vanoise National Park operates is that all hunting is banned. Hunting may have been part of the local cultural heritage – just as in our National Parks – but it was rightly seen as being incompatible with the conservation of nature and had led to the near extinction of the Ibex. The hunting ban has not just benefited Ibex but also chamois and other animals: forty years ago it was rare to see marmots, now they are everywhere and provide food for carnivores in a way that mountain hare should in the Cairngorms (and there are mountain hare present in the Vanoise too).

It goes further than than though. Carnivores are celebrated. The Vanoise National Park is promoted as a place where you might see anything from wolves to stoats and its role in promoting the re-introduction of bearded vulture into the Alps is celebrated (an incredible bird which I was lucky enough to see one near the Col d’Isere a few years ago). What a contrast to the Cairngorms and Loch Lomond and Trossachs where persecution of stoat,weasel and fox is accepted as a normal part of land management. Its only a short step from that to our Public Authorities acceptance of such persecution to issuing licences to cull protected species like Ravens in the name of other species.

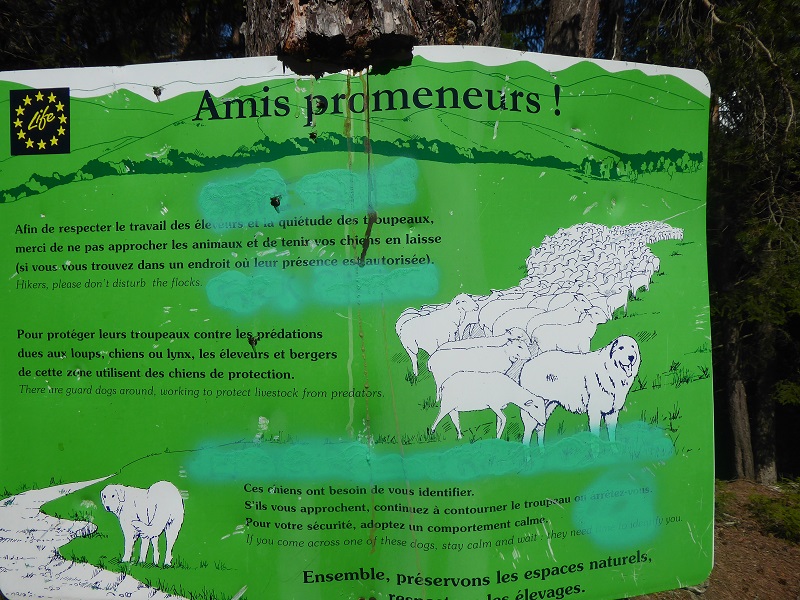

Rather than supporting species re-introduction, as in the Vanoise, both our National Parks are doing……… nothing. This is despite it being quite predictable that the beaver will return to both areas soon (unless illegally killed) and that unless our National Parks prepare for their return farmers will greet this with predictable (and partly understandable if misguided) outrage in which it will be argued that conservation is a threat to local livelihoods and so culls are needed. And as for the lynx or the wolf, their impacts could be managed to protect farmers, it just needs the will – as the photo illustrates.

The Vanoise National Park also far more “productive” in terms of biodiversity though in many ways its a harsher environment, with a significant area still covered by glaciers and most of the Park being snow covered for about hale the year. Despite these challenges there are about 30 pairs of golden eagle in the Vanoise National Park which covers an area 535 square kilometres. The survey of golden eagles in the Highlands in 2016 found 34 of 91 known golden eagle territories occupied in the east of Scotland which includes the Cairngorms National Park (which covers 4,528 square kms, about nine times the size of the Vanoise). The Vanoise ose eagles flourish despite their key prey, the marmot, hibernating for six months – and also despite occasional persecution and disruption of nesting attempts by outdoor recreation. If the core of the Cairngorms National Park or the wilder bits of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park were to follow the Vanoise model there we would I believe have many more pairs of golden eagles here – and a lot of other wildlife too.

Rather than seeing the hunting ban as a threat to livelihoods or culture, the dominant reaction of the ruling establishment in Scotland, the people living around the National Park who through the communes exercise a high degree of local control over land-use out, see its natural qualities as an opportunity. Mountain produce is heavily promoted and achieves a premium price. The Refuge d’Averole, where I stayed for a few days, provides almost totally organic and locally sourced food. All of this suggests very strongly that alternative forms of land ownership and land-use, which were not based on hunting estates, could work in our National Parks too if only there was the political will to do so.

A very interesting and revealing comparison. You hit the nail on the head when you say…”if only there was the political will to do so”. Our Scottish Government talks about consulting on uplands management and shows ‘politically correct’ concern when mountain hare culls are revealed. Unfortunately, as you say, nothing happens, except going along with what many of the estate landowners want.

There is no real vision in the Scottish Government of what National Parks should be about – protection of wildlife (flora and fauna) and rewilding – and the the considerable benefits that such programmes of ‘conservation’ can bring, including benefits to the economy. Instead our Scottish Government just seems to see national parks as enterprise zone opportunities for economic development using urban development models. It’s a long and painful road to make them understand the folly of their ways!

As a follow up to my earlier comment, I wonder how many of our MSPs and National Park Board Members have objectively read “Feral” by George Monbiot? It is the considered issues that George Monbiot raises in his book about rewilding that need to be debated. I’m not convinced that our MSPs and National Park Board Members understand these issues or even, if they have some awareness, have objectively considered them.

How about every Board Member, as part of their induction, being required to read certain books like Feral if they have not already done so? This would be much better use of their time than the current training on standards in public life which, for anyone with integrity should be a matter of common sense.

You are absolutely right. What we need is a ‘champion’ in a position of influence in the Scottish Government, or the leadership of our National Parks to get the issue of re-wilding firmly onto the policy agenda for our National Parks.