The £500 fine for a man who mistakenly shot a buzzard on a pheasant shoot raises some interesting questions about shooting in our National Parks.

The incident took place on the Ralia/North Drumochter estate – an estate in two parts – although its not clear which from the newspaper report. While I have seen evidence of intensive pheasant rearing on the Ralia part of the estate (above) I have also seen buzzards on several occasions in and around the policy woodlands by North Drumochter Lodge (photo below), most recently in November.

Aside from red grouse, I have seen very little bird or other wildlife on the North Drumochter Estate apart the Lodge buzzards and red deer (although I did see a Greater Spotted Woodpecker last time I was there). What I have seen (see here) are lots of corvid and other traps.

Trap by Allt Beul an Sporain west of Balsporran Cottages

Such traps can catch buzzards. That one can see buzzards quite easily on North Drumochter suggests that the Ralia/North Drumochter Estate tolerates or perhaps even likes them (releasing them from traps?) and it was quite possibly the estate that reported the man who shot the buzzard to the police. Imagine a responsible keeper before a pheasant shoot briefing the shooting party and telling them to watch out for other birds who then realises one of their clients has ignored their instructions. They would not just be very annoyed, they would also want to protect their reputation. Hence perhaps the report to the police.

Whether or not this is what actually happened, it should have. It seems wrong that not even in our National Parks is there a requirement for shooters to be able to correctly identify what they are shooting, have the self-control not to shoot unless they are 100% certain their target is legitimate and have the skill to do so. This is relevant to the long awaited review of grouse moor management: any shooting license should be dependant on shooters being properly briefed and trained and, where they are not and incidents such as this happen, the shooting license should be lost. The Cairngorms National Park Authority could take a clear lead here by developing a code of good practice for shooting in the National Park.

While there is still some deliberate persecution of buzzards, the persecution that once confined them to the North West corner of Scotland has ended and allowed them to re-colonise the rest of the British Isles. (I regularly see and hear buzzards in Pollok Park in Glasgow). What this illustrates is that is that while in general shooting interests perceive some raptors, notably hen harrier and golden eagle, as threats others are tolerated and what is tolerated has changed over time.

Pheasants v grouse

In 2014 the Cairngorms National Park Authority with Scottish Land and Estates commissioned a report on the Social, Economic and Environmental Contribution of Landowners to the National Park (available here). The research was in the form of a survey and there were 52 responses in all. The the returns on shooting make interesting reading.

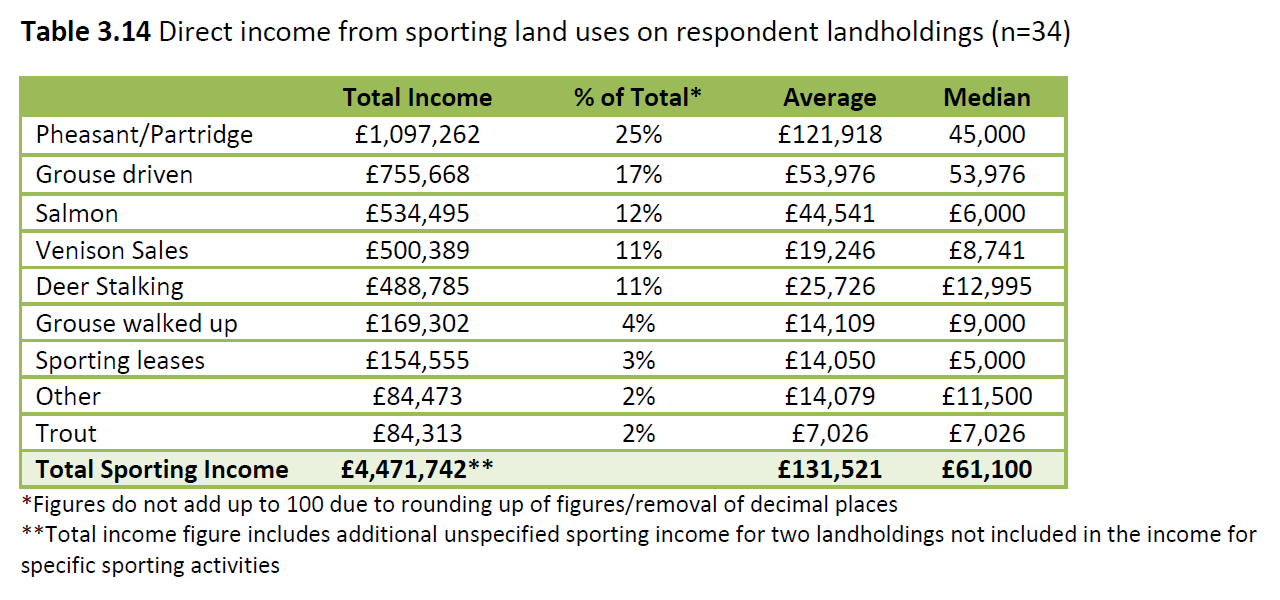

Now, not every landowner returned the survey and there may be problems with accuracy of the return (estates might not want to reveal their true income) but I was struck that pheasant shooting appears to bring in more income than driven and walked up grouse shooting combined. If income was what mattered estates would be focussing on pheasant/partridge shooting – and one might have thought the animals that predate on pheasants – rather than grouse.

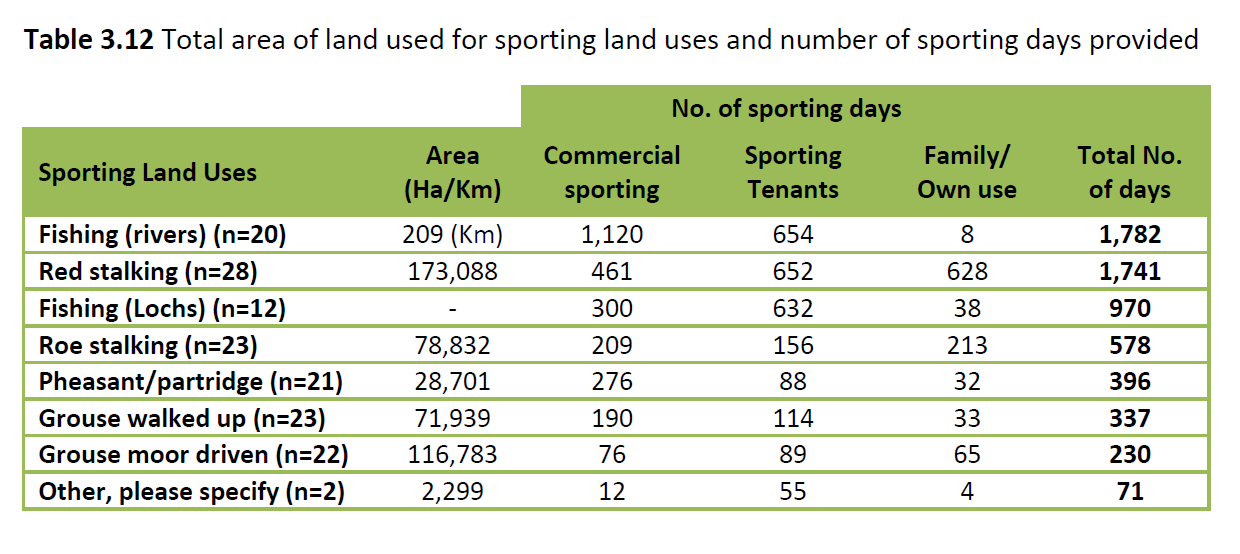

What’s more, pheasant/partridge shooting not only provides more days shooting than driven grouse shooting, in terms of land-use it takes place over a much smaller area than grouse shooting. As a consequence it produces far more income per hectare and – I would hazard – the costs per hectare are also a lot less. No need to install lots of tracks and grouse butts. Rearing pheasants, from an income perspective, appears far more rational than rearing grouse.

This, however, ignores the value of land which at present is driven by exclusivity rather than say ecological worth. Landed estates are valued by the number of deer or brace of grouse to be found on them because shooting red deer and red grouse has more social cachet than shooting, say, pheasants. You can see some of this in the estate returns above: the number of days pheasant shooting retained for family/personal use is 32 out of 396, less than 10%. The number of driven days grouse shooting reserved for family/own use is 65 out of 230 or over 25%. It appears that one is valued far more highly by owners than the other.

The converse to this is that any threat to what gives an estate its social cachet is a risk not just to the owner’s ability to enjoy what is so exclusive, it also threatens to undermine the price of the land and therefore their wealth. The consequence is that hen harriers, which are perceived as a fundamental threat to red grouse, are being persecuted to extinction, whereas buzzards – which occasionally will take red grouse (they are generalist predators who prey on what they can catch) – are tolerated.

What pheasant shooting shows is that even from a fields sports perspective there are more productive forms of land-use than intensive grouse moor management: planting or enable regeneration of woodland would enable more pheasants to be reared, which in return would allow greater revenue returns from the land. The problem is land values and land-use are not decided rationally but by the tastes and culture of an elite and at present their focus is on grouse. Until this is tackled raptors which commonly prey on grouse will be persecuted and others, which do not or do so only occasionally will be tolerated.

I don’t think the Cairngorms National Park Authority will be tackle the culture of the landed elite by persuasion. As a consequence, whenever a raptor crime takes places in the National Park, they need not just to discuss this with the landowners concerned – and I hope they meet North Drumochter to establish exactly what happened – they should be considering what changes they could introduce to regulate shooting.

Although your figures show pheasant shooting to be worth more to the economy than grouse shooting I feel these figures are inaccurate. The first reason for this is much more pheasant shooting is let to outside parties compared to driven grouse. There are several reasons for this most notably is considered a more prestigious sport and although the majority of guests will be invited friends and associates even though no money changes hand for the days sport many large business deals are done on the moors that has a direct effect on the economy. Another point is grouse moor management employs a larger number of people than a similar pheasant shooting both on the day and 365 days a year on hanekeeping staff etc.

A very good analysis of this report into the social and economic factors influencing hunting, shooting and fishing in the Cairngorms National Park. Although the comment from Andy Bell tries to criticise the figures, in the end I believe his reasons for criticising the figures just go to support what Nick Kempe says – there are non-economic factors which seem to influence many estate owners to dedicate so much of their land to grouse moorland and dear stalking. Understanding these influences is very useful in developing appropriate drivers to achieve ‘rewilding’ of more parts of the Cairngorms National Park.

What has CNPA done with this report since it was commissioned in 2014? The wheels of this mainly non-elected quango grind so slowly.