Following my visit to the Ledcharrie Hydro Scheme in Glen Dochart with members of the Munro Society (see here), I made an information request to the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park Authority to find out what they were doing to address deficiencies in the development, particularly the damage to the landscape that has been created by the new hill track. The LLTNPA’s initial response to my request was to refuse to give me ANY information apart from the dates of monitoring visits, claiming that they had not signed off all the works and provision of information could prejudice future enforcement action EIR 2017- 050 Response Ledcharrie. I treated this, as with so many responses from the LLTNPA, with a degree of scepticism, because I am unaware that they have ever taken enforcement action against hydro tracks, despite the large number of inappropriate and poorly restored tracks which now blight the National Park.

Leaving that aside, refusing to make public information that the developer was legally obliged to provide as a condition of the planning consent was in my view completely unjustifiable and I asked for a Review. The LLTNPA has now backtracked EIR REVIEW 2017-050 Response Ledcharrie hydro scheme and at the beginning of August sent me no less than 45 documents on a CD. This post considers what the information tells us about how the LLTNPA is “managing” the impact of hydro developments on the landscape of the National Park.

The information required as a condition of the planning consent

The Planning Consent which the Park’s officers agreed in December 2013 included 18 conditions, each of which required the Developer, Glen Hydro Ltd acting on behalf of Auchclyne Estates, to submit further information for approval before the development could go ahead. This information includes assessments required (eg wildlife surveys), more detailed plans (eg for the powerhouse and track construction), standards governing the work and reporting arrangements. Similar information and conditions are required for most planning consents for hydro developments. In my view all such information should be public – people should have a right to know what has been agreed between planning authorities and developers – and it appears that the LLTNPA now agrees. Over half the documents on the CD relate to the plans, reports and proposals the Developer had made to fulfil these conditions.

Unfortunately the information is not properly indexed by the LLTNPA and they have not told me whether they are still withholding information about the fulfilment of some of the conditions. But, as far as I can tell from what has been supplied, Glen Hydro Developments did supply information on each of the 18 planning conditions. The file sizes are large but the content is summarised in the chart on pages 6-12 here.

What is far less easy to see is what documentation was agreed by the LLTNPA. Some conditions, including the first, to produce a Construction Method Statement, were clearly approved Condition 1, 3, 6, 7, 8 and 9_20150827_Discharge of conditions. For others its very hard to tell. For example, in relation to condition 12 on the design of the powerhouse, the Developer appears to have done everything the Park had asked Condition 12_20160314_Agent to NPA but there is no final sign off the from the LLTNPA. Another example is that the Developer clearly stated that they would include information on several of the conditions (2,4,14) in the all important Construction Method Statement, but in approving this document (see above) the LLTNPA did not clearly say whether those other conditions contained in it were also discharged.

In my view our National Parks, which are meant to be beacons of good practice, should be publishing information about the discharge of planning conditions on their planning portals so its readily available. This should include both the information supplied by the Developer and the documents from our National Parks signing it off, the two clearly referenced. This would empower the public and avoid the need for need for endless information requests. The LLTNPA’s current stance however is it doesn’t make this information public because it doesn’t have to legally – so much for being a beacon of good practice! In fact if the LLTNPA made these documents public, I think it would improve their practice because where approvals are unclear, as at Ledcharrie, they would be challenged. This would also help Developers who are left in a difficult position when they are not clear about what has been approved either. Its worth noting that Glen Hydro developments appears to have taken a far more systematic approach to the provision of information needed to disharge planning conditions – judging by their chart – than the LLTNPA.

What the information tells us about planning standards and protection of our landscape

Much of the documentation supplied by Glen Hydro and approved by the LLTNPA is excellent, for example it shows that lots of care is taken to ensure that walkers are informed of alternative routes and is a credit both to National Park staff and to developers. However, what the EIR response also shows is that standards and documentation are much better developed in some areas than others. So, the planners, whose stock in trade is new buildings, took huge amounts of care about the design of the powerhouse (see link to condition 12 above). They also, because of environmental regulations, require very detailed information about the potential impacts on protected nature sites (informed by advice from SNH and their own ecological staff which is included in committee reports) and how these will be mitigated. They also took great care with any aspect of the environment regulated by SEPA (hence all the plans to prevent stop silt filtering into watercourses). All this shows that regulation and rules do work.

Ironically, because this is what the National Park was set up to protect, what the planners are not so good at is protecting the landscape, and more specifically the impact of new hill tracks. Ledcharrie shows the problems were created even before planning consent was granted. Here is what the Committee Report said:

- “Effects on Landscape Character: There would be no significant adverse effects on the site landscape, published landscape character types and the designated National Park are predicted after construction is complete.”

and

- the topography will screen the intakes, the pipe route will be restored, the track returned to its original state and the tailrace and powerhouse be assimilated in the landscape.

Wishful thinking does not make things happen. This weakness is carried through into the Construction Method Statement approved by the LLTNPA (see here). The section headed Access Track is brief to the extreme, in contrast to other sections, and mainly about silt:

What the EIR Response shows is that in discharging this condition the LLTNPA agreed a far broader track than was reported in the the Planning Report and mentioned in my original post:

“A permanent track from the powerhouse to the primary intake (surfaced with local crushed stone and about 2 metres in width).”

In agreeing to a 3m broad track the LLTNPA also ignored its own good practice guidance which Gordon Watson, the Park’s Chief Executive stated should mean tracks are 2m broad except on bends where they may be 2.5m broad. No wonder the Park did not want this information to be made public!

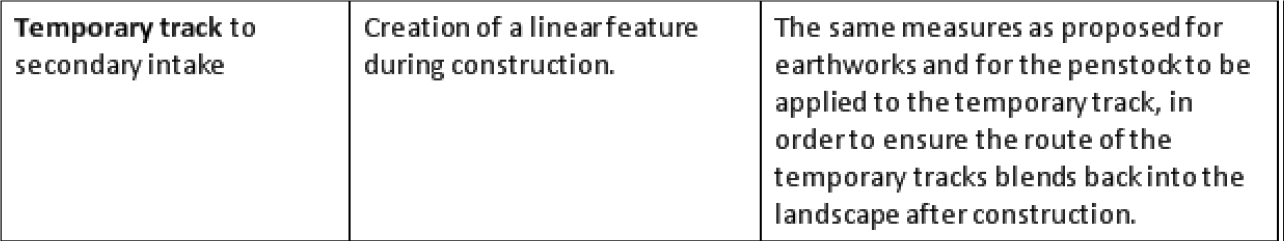

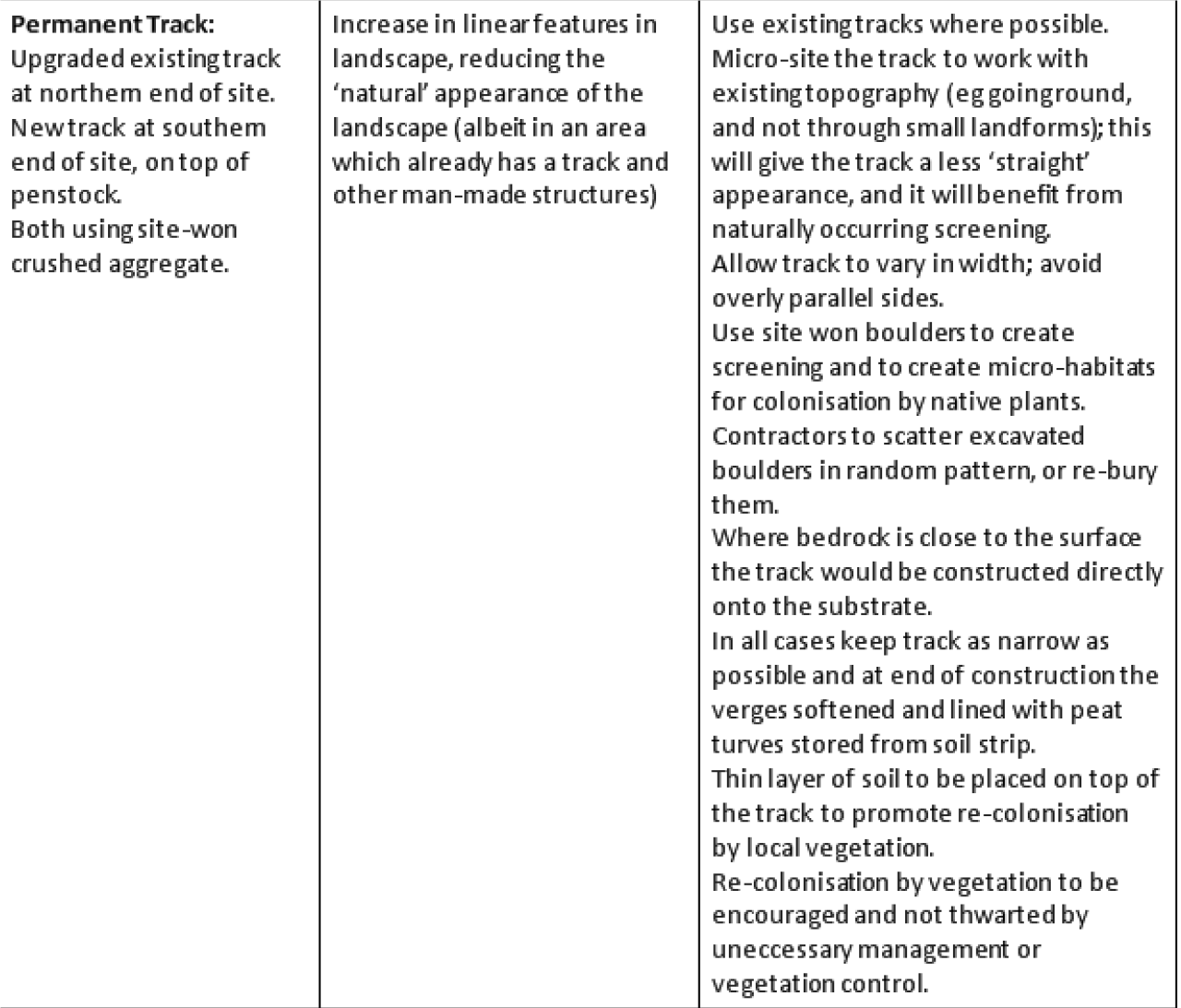

The Construction Method Statement did contain some further information on track construction and restoration under a section on Landscape Mitigation measures:

The problem is this is not a proper Construction Method Statement. It says nothing about the angle of the track – key to future erosion (SNH tracks recommends a maximum angle of 14 degrees), the design of culverts or the angle of verges all of which have contributed to the adverse impact this track is having on the landscape:

The problem is this is not a proper Construction Method Statement. It says nothing about the angle of the track – key to future erosion (SNH tracks recommends a maximum angle of 14 degrees), the design of culverts or the angle of verges all of which have contributed to the adverse impact this track is having on the landscape:

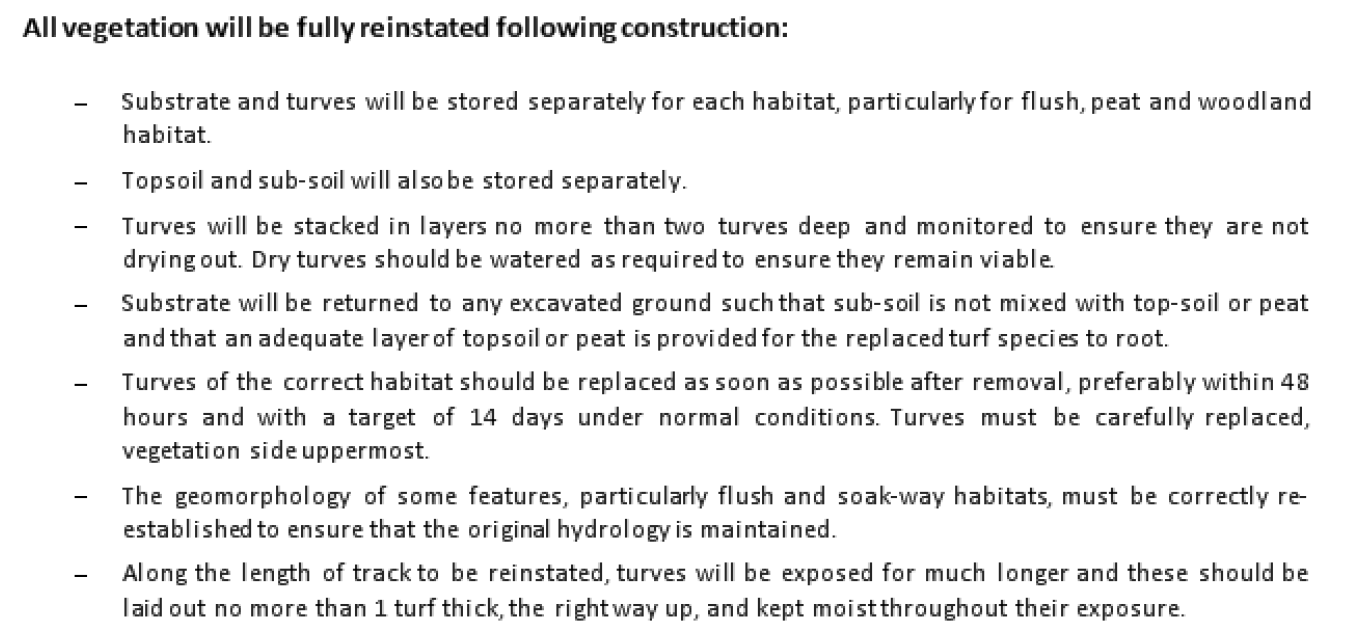

Where the Construction Method Statement is stronger is the restoration of soil and ground vegetation:

I believe this helps confirm my analysis. The LLTNPA has been good at ensuring that ground above pipelines has been restored well. In this case the techniques for ensuring such restoration have also been applied to tracks. The problem however is that if you get the track construction wrong (angle of slope, cutting through banks etc) that is much much harder to restore than land above a pipeline.

The lesson I think that the FOI material tells us is that the LLTNPA (and indeed other planning authorities) need to pay far more attention to the specification of tracks and use this to inform whether tracks should become permanent or not.

Following on from that, if its not possible to create a track which does not meet all the requirements of SNH’s excellent guidance on hill track construction, that should be an indication to our planning authorities, that these construction tracks should only be temporary and be fully restored, just like the pipelines.

The monitoring of the construction of the Ledcharrie hydro and enforcement of planning conditions

The LLTNPA has not given me a single document about enforcement of the planning conditions, claiming this might prejudice future enforcement action. While this might be the case in some circumstances – for example legal advice – one would hope that the Developer would have been told by the LLTNPA which conditions it has so far failed to meet. If so, its hard to see how provision such information could prejudice enforcement action. If the Developer knows the concerns of the LLTNPA, why shouldn’t the public? I suspect the reason for refusing this information is that if it became public more evidence would become available about the LLTNPA’s failure to enforce planning conditions. This is far too systematic to be the fault of staff who I believe have neither the time or the expertise necessary to monitor these schemes properly.

Instead, staff depend on is Monitoring Reports and work from the “independent” Ecological Clerk of Works (who is contracted by the Developer and who is therefore dependent on the Developer to get paid). The other suite of documents in the EIR response are 19 Monitoring Reports from the Ecological Clerk of Works (some of which cover several visits).

While these monitoring reports contain good things – the reports show for example that the Ecological Clerk of Works consistently identified issues with silt traps and actioned these – and many interesting photos, I believe they also help explain why the hydro track at Ledcharrie is the mess it is. The problems are illustrated early on:

This photo shows that turves were not being stored as had been specified in the Construction Method Statement – one layer deep and the right way up – but instead have been dumped in a heap. The Ecological Clerk of Works makes no comment on this by the picture and no mention in the body of their report.

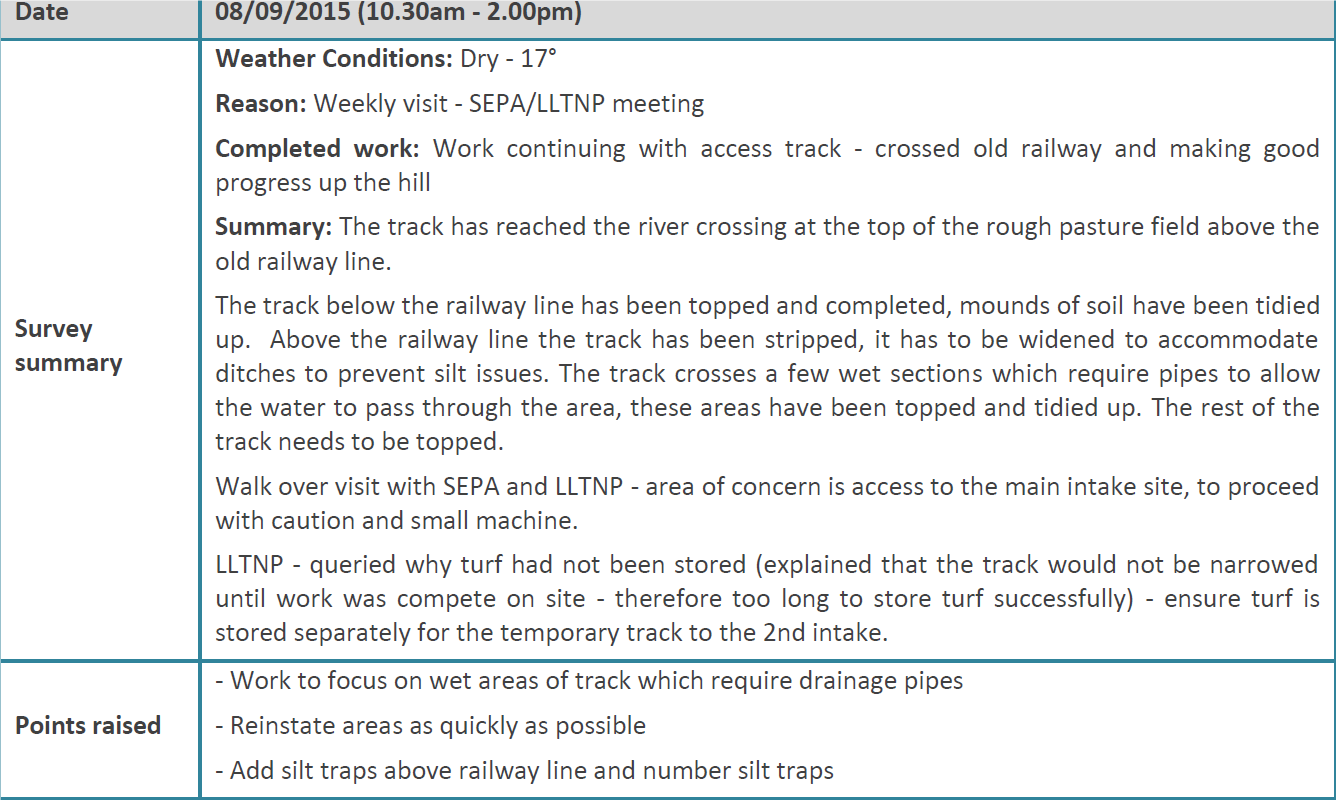

To their credit, the LLTNPA planning officer identified this as an issue. We only know this not from information recorded by the LLTNPA but because its mentioned in the next suite of monitoring reports from the Ecological Clerk of works (ECOW) which includes this :

:

Having asked why the turf had not been stored correctly, the member of the planning team apparently then accepted the claim by the ECOW that the turf could not be stored successfully for long periods. This is garbage. Why did the Construction Method Statement say that turf would be stored in this way if it couldn’t? Actually, I have just seen an example on the Ralia estate (which I will cover in due course) where turf was stored successfully for over three years. Unfortunately, the LLTNPA appear to have accepted this claim, instead of challenging the ECOW and the Developer, and this helps explain much of the more restoration work alongside the track.

Its worth having a look at the report (20151007_Condition 18_Monitoring Report_Sep 2015. which has nteresting photos but bear in mind its right from the start of the works and only covers certain issues. A couple of the photos show oversteep banksides, the ones that are now have such an adverse impact on the landscape as they are too steep to be restored. Again there is no comment from the ECOW. That’s maybe not their fault – their primary remit after all was for ecology, not landscape – but its a serious problem the LLTNPA needs to address.

The lessons that need to be learned from the information released by the LLTNPA on Ledcharrie hydro and what needs to change

The documents released by the LLTNPA tell us nothing about what the Park is doing to redress the damage caused by the construction of the Ledcharrie hydro, but they do tell us a lot about what is going wrong and I strongly suspect a similar tale could be told for many other hydro schemes in the National Park.

- Far too little attention is given to the way track to hydro schemes are constructed in the planning process prior to work starting. I think at the very least all proposal for tracks should have a specification which covers every aspect of SNH Guidance on the Design of Hill tracks (see here) and our National Parks and other planning authorities should evaluate proposals against that guidance

- It appears that at present planning staff do not have the expertise necessary to ensure high standards of track construction nor are they able to call on this expertise from elsewhere (as they can with other specialist areas). Our National Parks need to address this skills gap.

- Unfortunately, it also appears that the Ecological Clerks of Works lack expertise in this area too and its imperative that if our National Parks continue to get Developers their own practice that they engage people with the right skills. That might mean a specialist track consultant.

- The problem for both our National Parks and developers is that there is little evidence that there are currently people involved in hill track construction with the expertise to ensure tracks are designed to high standards and also to advertise where permanent tracks would have a deleterious impact on the landscape. One solution would be for our National Parks and developers to engage people involved in footpath design to carry out this work. In general the standards that are applied to footpath design are far far higher than those applied to hill tracks. This might help provide permanent jobs to the people currently being trained as footpath workers in our National Park.

- The biggest failure of all though is a lack of will. There appears to be no ethos in the LLTNPA which encourages staff to take action when they identify things that are going wrong, secure in the knowledge that they will be backed to the hilt by their Managers and the Board. Instead there is a development free for all which is undermining the entire credibility of the National Park Authority and will in the long-term destroy tourism, as its the landscape which is the reason why people visit our National Parks in the first place. Then, when the results of this free for all are made public, suddenly the LLTNPA says it is considering enforcement action. If action had been taken at the beginning of the construction at Ledcharrie, most of the issues could have been prevented.

- As a start to rectifying these planning deficiencies, the LLTNPA should now commission an independent audit of a selection of hydro developments in the National Park causing public concerns. This should analyse in how many cases the LLTNPA has approved tracks which breach its own best practice guidance and ask for recommendations about how this could be prevented in future.

- In order to show a collective determination to tackle these issues, I think that the LLTNPA should no longer delegate decisions about hydro schemes to staff. Like in the Cairngorms National Park Authority, all decisions about hydro schemes should be taken in public at the Planning Committee.