By Nick Halls, resident of Ardentinny

This is the fourth in a series of articles about the Argyll Forest part of the National Park where I live (see here).

Recently, as a stage in forestry operations, fencing seems to have proliferated. In the past fencing was usually used to exclude stock from the forest, as sheep purportedly damaged trees, but benefited from using the trees as shelter during bad weather. Apparently, sheep able to shelter in the forests maintain their weight and are more robust at lambing time, increasing the probability of raising twins.

When I first arrived in Ardentinny, there was an ongoing squabble between local sheep farmers and the Forestry Commission about maintaining fencing. Outdoor instructors were caught in the cross fire as scapegoats, accused of damaging fencing by both parties. In practice, wherever fences were crossed regularly styles were constructed, but in many cases fencing was old and decayed.

After the great storm in 1968, the issue evaporated as Forestry trees were blown over destroying stock enclosures, throughout the forestry estate. I assume the Forestry Commission was liable because it was forestry trees that did the damage!

Ordinary stock fencing does not impede access very much, it’s annoying but not insurmountable, and can usually be negotiated without damage as long as a fence is in reasonable condition. Informal styles can be erected. Now it seems that as stock rearing declines the beasts to be excluded are deer and people.

There seemed to be a resident Red deer and Roe deer population [often interbreeding with non-native Sika deer] but there was also long range migration of Red deer during bad winters. For years, the local Red deer population migrated from pasture to pasture virtually unobstructed. They were informally described as ‘bed and breakfast’ deer as they lived in the woods and grazed on open hillsides. Due to this way of life they were often bigger than the deer on stalking estates, and more akin to the forest deer of Europe. It was once suggested that there were two species, one a forest species and the other an upland, open hillside species [a distinction might have arisen due to interbreeding with Sika deer].

This seems to suggest that fencing, whether to keep deer out of forests or on an open stalking estate, has an impact on the condition of beasts, and interbreeding with a dilution of the pure bred native species. Bread and breakfast deer tend to do well, and the open hillside deer often fail to survive severe winters, underweight and starving, especially in over stocked localities from which they have difficulty migrating.

Recently I have seen far fewer Red deer, and those observed seem to be single deer rather than part of a group. The red deer population may have been culled.

I recall being told how important ‘wildlife corridors’ are to maintaining wildlife populations and bio diversity.

‘A wildlife corridor is a link of wildlife habitat, generally native vegetation, which joins two or more larger areas of similar wildlife habitat. Corridors are critical for the maintenance of ecological processes including allowing for the movement of animals and the continuation of viable populations’ ‘separated by human activities or structures [such as, roads, development, or logging].’

The increasing use of deer fencing to parcel out areas of forest or rough grazing effectively reduces access to much of the land, particularly the open hill, for both man and beast. I seem to recall the aspiration of the Forestry Commission in Scotland was once a fenceless forest estate.

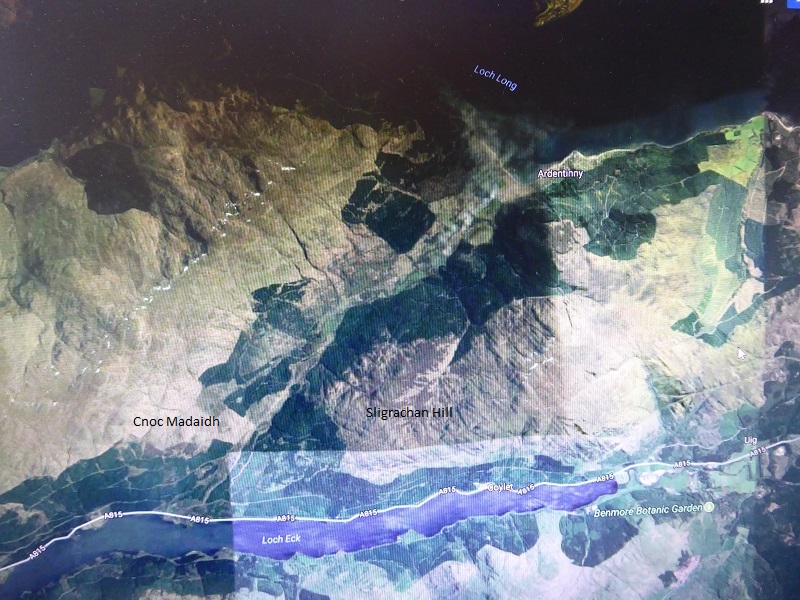

The bealach between Glen Finart and Loch Eck side is called the Larach [presumably because there was once a homestead or shieling on the Larach Hill]. High ground connects the open hillsides of Sligrachan Hill with the open hillside above Cnoc Madaidh, during two cycles of forestry activity it remained, intentionally or otherwise, a ‘corridor’ for deer migrating to the open hillside to the north, and back to the more sheltered forestry edge, which is sheltered from the prevailing westerly gales.

The bealach between Glen Finart and Loch Eck side is called the Larach [presumably because there was once a homestead or shieling on the Larach Hill]. High ground connects the open hillsides of Sligrachan Hill with the open hillside above Cnoc Madaidh, during two cycles of forestry activity it remained, intentionally or otherwise, a ‘corridor’ for deer migrating to the open hillside to the north, and back to the more sheltered forestry edge, which is sheltered from the prevailing westerly gales.

The public road and forestry access roads did not constitute significant obstructions to deer movement as traffic is light during the day and almost absent at night. The following photographs, all taken from public or forestry roads, show how the corridor has been obstructed by deer fencing,

This fencing is to protect an area of natural regeneration or planting with native trees, but it has only two access points. I am not sure how effective it is for excluding deer, as I have observed deer clear such fencing from the uphill side by an almost standing jump, but it certainly excludes me from whichever direction I approach it.

Informal crossing is obviously difficult, but extended lengths of fencing with no robust straining posts implies attempts to cross by climbing over is likely to damage the fence.

The grazing pressure does seem greater outside the fence but it effectively excludes access by humans. It also makes one wonder whether, if the habitat inside the fence needs to be protected at this stage, how natural the regeneration will be if it will eventually have to survive grazing by deer. It seems incoherent to try to create an ecological community, that will eventually include deer, by initially excluding them from it! I seem to recall that such fencing is to be removed, but have not noticed any sign of older fencing around more mature forest planting being removed.

Other examples in the same area, probably less than a square kilometre.

This very new deer fencing replaces a stock fence, it’s not clear why if a stock fence has sufficed for half a century or more. It is not immediately obvious whether it is to keep deer in or out, but it encloses a big area that used to be part of an orienteering map, used for National Competitions.

The enclosed area used to be informally called the ‘Park’, and used for seasonal grazing of sheep gathered from the hillside between Glen Finart and Loch Goil, and farmed jointly by farmers from the same family at Sligrachan and Carrick.

This fencing excludes access to very closely planted Scots Pine. I am not conversant with its original purpose, but one would imagine it is about time it was removed. I am not sure why planting has to be so close, but presume it must be so that ‘survival of the fittest’ allows some trees to ‘reach for the sky’ growing straight and thin, with few side branches, while others are shaded out and die off. In the Sitka plantations, such dead and dying trees are not thinned, but fall and further obstruct access.

Looking at this hillside, compared with nearby remnants of mature Scots Pine groves [on the sky line], it seems likely that as many as two thirds of the trees will never reach ‘economic’ maturity, and substantial mortality will occur to get a viable crop of similar sized trees. If such a high proportion of trees are going to die or be thinned, one wonders why bother to fence it as beasts are unlikely to do the equivalent amount of damage. There seems no obvious difference between the grazing pressure within and outside the fencing, one would imagine that the economic value of the eventual crop will be similar, inside and outside the fencing.

I am not sure why this fence was emplaced, but it excludes access directly from the road, but more significantly obstructs access to the road for someone coming off the hill, on a winter’s day in poor light. Circumnavigating it might add a kilometre or more of additional travel.

The combination of impenetrable forest and deer fencing could pose a serious hazard for an unwary visitor, descending from Beinn Ruadh via Sligrachan Hill, by increasing the risk of being benighted, injury and exhaustion/exposure. Such obstructions are not shown on a GPS or OS 1:50,000 map.

Post script

Soon the poseur, ‘survivalists’, given unwarranted promotion by the media, who have encouraged much of the egregious recreational behavior witnessed today, e.g. campfires, disposable BBQ’s, fragile folding seats, and semi disposable popup tents, will be recommending naïve urban adventurers to carry a bush knife and wire cutters, with their multi tools, folding saws and GPS.

‘The leave no sign, do no damage, and pass as if you have never been’ philosophy has been undermined by a marketing operation and commercial imperative to turn outdoor recreation equipment into a mass consumer market at considerable cost to the environment.

Between 1965 and 2000, thousands of children journeyed through the area and camped, during expeditions from the formerly numerous outdoor education establishments – they left so little ‘sign’ they might never have existed. A similar thing could be said of the School camps, summer camps for children organized by churches and Scout Groups who used the area from the 1930’s onwards. It is equally true of youngsters currently involved in Duke of Edinburgh Award Expeditions, who are now restricted to Forest Roads and manufactured paths, rather than being ‘impelled’ into an experience of wild countryside.

Little wonder visitors may think they can arrive in a car, walk ten steps and have a wilderness experience, but this lack of real connection is fabricated by a progressive removal of possibilities to do anything much more adventurous, than ‘Park & Pitch’. Already over used and abused sites do not encourage respect, but confirm urban values and an expectation that it is somebody else’s responsibility to tidy them up after use. This is evident at the Duck Bay picnic area.

I am persuaded that influences are interactive; distorted media presentations of outdoor experience that are hard to distinguish from marketing, sales of useless fragile outdoor equipment, restriction of access causing concentrated use of ‘honey pot’ sites, destructive behavior by people unused to handling themselves in the countryside and land managers deciding to exclude them from their land.

This is re-inforced by the disinclination of the operators of caravan and chalet parks, developed on the site of former camping grounds, to cater for campers at all. The result is ‘exclusion’ of temporary visitors of all descriptions, with a reduction of ‘visitor experience’ to an urbanized familiarity, against a back drop of hills, forests and lochs.

This discourages access to the NP, other than day visits, by people barely able to afford a social rent, or who are saving for a deposit for a first home, or intermittently have to resort to food banks, but favors ‘exclusivity’ for second home owners [a residential caravan apparently costs about £39,000, plus site rental and Council Tax].

I feel this is not what a National Park should be all about!

I was with you until the postscript – which appears to be an unconnected rant based on a belief that the past was always better, and/or that the countryside should only be available to the elite with the right knowledge and equipment to “properly” explore it.

I’d be interested to know if more or fewer people now explore far from where they park, in the style approved of by the author (I suspect “more”) – and the extent to which the “park and pitch” activity that the author clearly looks down on is nowadays often the stepping stone to more engagement with the countryside rather than the more formal (and limited) routes he fondly looks back on.

Nowadays people are generally more mobile and there are many more ways that they can enjoy the countryside. Over time this enjoyment can often develop from casual days out to something more serious. Similarly the private sector (and media) has become more sophisticated in it’s ability to cater for these many and varied choices. For example, why whinge about “fragile outdoor equipment” when it is probably fine for the day tripper or “overnighter” – and when there is plenty of much more robust (and expensive) equipment available than ever before, for those who want to try something more serious?

Andrew Nick Halls away in pyrenees so I doubt he will respond soon! NICK has written and referred in article to loss of roadside camping places too.